History is made in the “nooks, crannies, and margins of empire,” writes Modibo Kadalie, a lifelong organizer, grassroots historian and author of the forthcoming book, Pan-African Social Ecology from On Our Own Authority! Publishing.

Kadalie and editor Andrew Zonneveld have compiled a short book of speeches, conversations and essays on pan-Africanism, national liberation and environmental movements. The collection of Kadalie’s work is vast in scope, standing firmly on its under-recognized intersections, narrated through Kadalie’s many decades of work at the grassroots level in trade unions, the liberation of the Global South and Black liberation movements in the U.S.

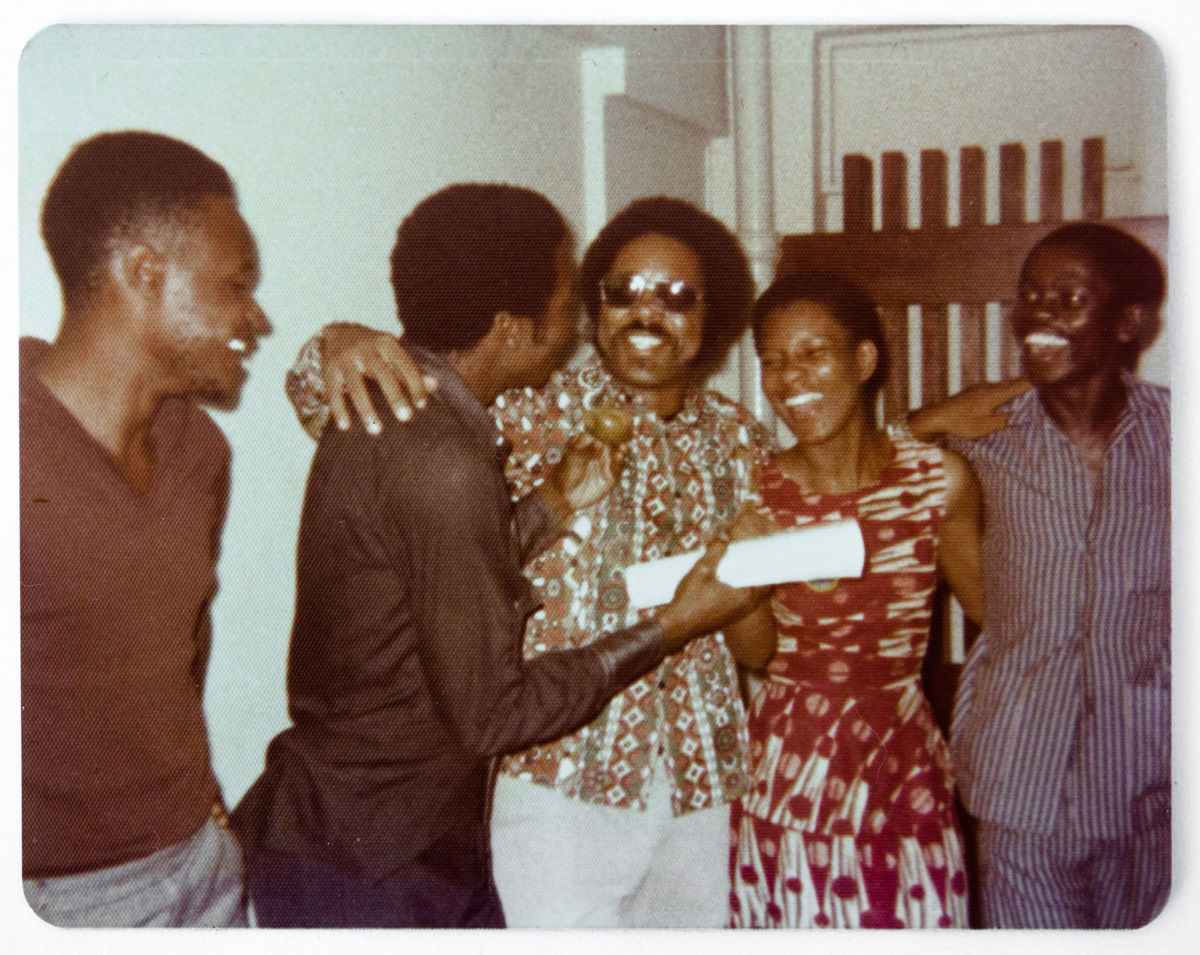

Kadalie lays out decades of trials and tribulations in a formidable firsthand account of his participation in the anti-colonial and anti-racist struggles of the 1960s. From organizing with the African Support Liberation Committee and collectively deciding to bar politicians from speaking at their events, to publicly condemning the revered Southern Christian Leadership Conference for its financial ties to Gulf Oil and Portugal’s colonial operations in Angola, he elevates key moments in Black working-class history with the grit of a seasoned organizer and care of a serious historian. Through his retelling, Kadalie shares key insights for movements wrestling with political questions of representation, leadership structures and transnational solidarity.

Reflecting on the failures of postcolonial states to democratize power, Kadalie argues that people engaged in social-ecological movements must turn to each other to offer the protection and infrastructure that the state fails and refuses to provide. “People don’t have to vote on that kind of stuff, you know? They just see what needs to be done and they do it,” he writes. “They organize it themselves. Someone brings a shovel, someone else brings a bag, one guy lifts this, one guy carries that, someone else drives the pickup truck — you can see it in action.”

Pan-African Social Ecology expounds on a liberatory ecological politics in plain English for the exasperated environmentalist looking to fundamentally integrate issues of race, empire and direct democratic organizing into their political practice. Readers will follow Kadalie as he recounts his lifelong journey of political reorientation in learning from the failures of Black- and Brown-led neocolonial states and working to fundamentally reorient our communities to make decisions from the bottom-up about how we fit in to the rest of the natural world.

For Kadalie, a new politics empowers everyday people to make direct choices about the trajectory of their lives, organically develop their political consciousness and function healthily among others in community. Without the closeness of intimate community, Kadalie argues, movements are destined to commit the same errors of vertical leadership that doomed the movements of his own time. The collection espouses leaderlessness as an antidote to executive board-style organization and an armor against racism, misogyny and homophobia in movement spaces.

Guided by the principles of anti-capitalism, a healthy disrespect for authority and a recognition of humanity’s embeddedness in nature, a new pan-African social-ecological ethics provides a framework for understanding the fundamental connections between social and ecological problems, and a possible roadmap out. Resilient and effective communities, Kadalie argues, root out pyramidical structures of leadership and cultivate a culture of popular participation at all levels of decision-making. Pan-African social ecology makes a clean break with representative democracy: to dismantle the nation-state, we must build up an engaged citizenry ready to determine the conditions of their lives in intimate connection with others.

For the newly politicized, the book offers a useful reflection on the pan-Africanist movements of Kadalie’s day, highlighting its successes, blunders and legacies, while introducing concepts of anti-statism, anti-capitalism and community-building.

For the experienced organizer, the real beauty of the book is in Kadalie’s practice of auto-ethnography as a movement participant. As organizers, striking the imperative balance between the individual and the collective, no less retrospectively, is a monumental task that Kadalie has achieved here with grace, warmth and wisdom.

“History must be rewritten from the point of view of these freedom-seeking resisters, not merely as individuals but as an entire freedom movement,” Kadalie writes. In this, he surely gifts us his own history replete with an abundance of lessons to learn and ideas to put into practice.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.