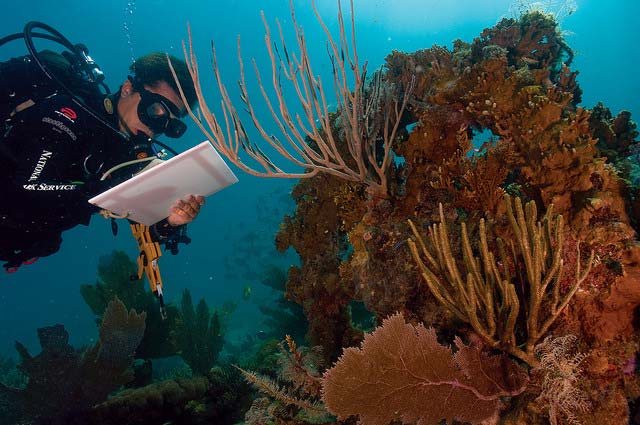

The incredible diversity of coral reef ecosystems is being threatened by factors associated with global climate change and local pollution. Today diseases have increased and are killing more corals. Seeing this increase in frequency and severity of diseases affecting coral reefs around the globe, we have made learning more about coral immune systems a priority.

At the University of Texas at Arlington we are addressing one area of knowledge that has been lacking – making sense of disease patterns and figuring out why some species are disease susceptible and some resistant. Our research, recently published in the journal PLOS ONE, focused on 14 species of Caribbean corals and found that, suprisingly, the older species are doing better.

To reach this conclusion, we worked with Ernesto Weil at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez. The Caribbean, including Puerto Rico, has been hit particularly hard by disease outbreaks. Up to eight different diseases affect species there, with many outbreaks causing significant mortality on the reef.

We amassed 140 samples of healthy Caribbean coral spanning 14 species from reefs closely monitored by Weil. We then developed a phylogenic tree, a kind of map that traces the evolutionary history of corals, which allowed us to group them according to the time they diverged as a species. Some of the oldest corals in the study, such as Porites astreoides or “mustard hill coral”, have been around for more than 200m years, while others diverged to become a new species as recently as 7m years ago.

Ocean health and diversity are inexorably linked to the coral reefs around the world, not to mention the fate of industries such as fishing and tourism. The threats of pollution, overfishing and climate change have weakened species and made them more susceptible to conditions such as white plague and yellow band disease.

When a disease outbreak hits a reef, it can kill up to 50% of a specific species. This loss of species can change the structure of reef along with the fish and animals that use it. This can reduce the characteristic colour and beauty we associate with reefs. To keep coral reefs “teeming with life”, corals need to be healthy and there needs to be a diversity of species.

Species that have been around for longer and experienced and survived stressful events are more resilient. The goal of our work was to test this hypothesis with respect to disease and immunity.

We assembled information about the diseases affecting each species and then looked at base-level immunity in the lab. We analysed each data set to determine whether a “phylogenic signal” existed. A phylogenetic signal is when organisms in closely related species have characteristics that are more similar to each other than they are to more distant species.

Extracting proteins from the coral samples allowed us to conduct immune assays testing six immune traits that we thought showed a good overall picture of a species’ disease susceptibility. Two factors in particular – the inhibition of bacterial growth and melanin concentration – were higher in older corals and likely play a role in disease resistance. For example, coral species that diverged over 200m years ago can kill up to 41% of bacterial growth, versus just 14.6% in newer coral species. Corals with higher concentrations of melanin in their tissues may be better prepared to kill a pathogen before it can establish and cause an infection.

The disease patterns seem to bear out the lab findings – with the “modern” lineages we examined suffering as many as eight different diseases and “older” lineages suffering as few as one. While these results are confined, for now, to Caribbean species of coral, we are excited about the potential new avenues for research these results may take us both in other locations around the Caribbean and around the globe.

This work provides both an explanation and the basis for a look into the future. Coral reefs continue to undergo stress, and some species will handle this better than others. Our research provides clues that the older species may be more likely to survive current conditions and helps understand why that is.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we have only 72 hours left to raise $25,000. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.