Many individuals who follow politics and journalists think that the right-wing playbook began with the Koch brothers. However, in her groundbreaking book, Nancy MacLean traces their political strategy to a Southern economist who created the foundation for today’s libertarian oligarchy in the 1950s.

Mark Karlin: Can you summarize the importance of James McGill Buchanan to the development of the modern extreme right wing in the United States?

Nancy MacLean: The modern extreme right wing I’m talking about, just to be clear, is the libertarian movement that now sails under the Republican flag, particularly but not only the Freedom Caucus, yet goes back to the 1950s in both parties. President Eisenhower called them “stupid” and fashioned his approach — calling it modern Republicanism — as an antidote to them. Goldwater was their first presidential candidate. He bombed. Reagan, they believed, was going to enact their agenda. He didn’t. But beginning in the early 2000s, they became a force to be reckoned with. What had changed? The discovery by their chief funder, Charles Koch, of the approach developed by James McGill Buchanan for how to take apart the liberal state.

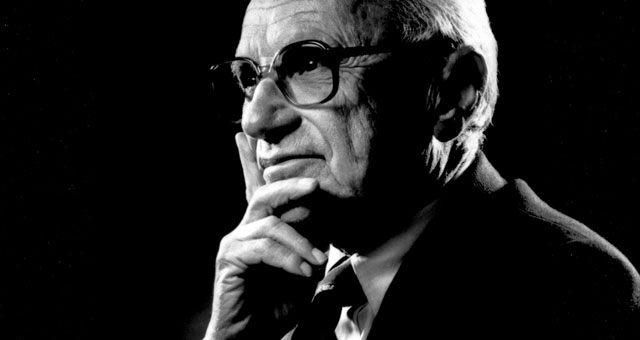

Nancy MacLean. (Photo: Viking Books)Buchanan studied economics at the University of Chicago and belonged to the same milieu as F.A. Hayek, Milton Friedman and Ludwig von Mises, but he used his training to analyze public life. And he supplied what no one else had: an operational strategy to vanquish the model of government they had been criticizing for decades — and prevent it from being recreated. It was Buchanan who taught Koch that for capitalism to thrive, democracy must be enchained.

Nancy MacLean. (Photo: Viking Books)Buchanan studied economics at the University of Chicago and belonged to the same milieu as F.A. Hayek, Milton Friedman and Ludwig von Mises, but he used his training to analyze public life. And he supplied what no one else had: an operational strategy to vanquish the model of government they had been criticizing for decades — and prevent it from being recreated. It was Buchanan who taught Koch that for capitalism to thrive, democracy must be enchained.

Buchanan was a very smart man, the only winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics from the US South, in fact. But his life’s work was forever shaped by the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision. He arrived in Virginia in 1956, just as the state’s leaders were goading the white South to fight the court’s ruling, a ruling he saw not through the lens of equal protection of the law for all citizens but rather as another wave in a rising tide of unwarranted and illegitimate federal interference in the affairs of the states that began with the New Deal. For him what was at stake was the sanctity of private property rights, with northern liberals telling southern owners how to spend their money and behave correctly. Given an institute to run on the campus of the University of Virginia, he promised to devote his academic career to understanding how the other side became so powerful and, ultimately, to figuring out an effective line of attack to break down what they had created and return to what he and the Virginia elite viewed as appropriate for America. In a nutshell, he studied the workings of the political process to figure out what was needed to deny ordinary people — white and Black — the ability to make claims on government at the expense of private property rights and the wishes of capitalists. And then he identified how to rejigger that political process not only to reverse the gains but also to prevent the system from ever reverting back. He sought, in his words, to “enchain Leviathan,” which is why I titled the book Democracy in Chains.

Why, until your book, has his importance to the right wing been largely overlooked?

There are a few reasons Buchanan has been overlooked. One is that the Koch cause does not advertise his work, preferring to tout the sunnier primers of Hayek, Friedman and even Ayn Rand when recruiting. Buchanan is the advanced course, as it were, for the already committed. Another is that Buchanan did not seek the limelight like Friedman, so few on the left have even heard of him. I myself learned of him only by serendipity, in a footnote about the Virginia schools fight.

His importance to the right wing could only be identified by working through the archival sources that provide context for his published work. That’s what I did after discovering that Buchanan had urged the full privatization of Virginia’s public schooling in 1959, and then learning that he later advised the Pinochet regime on a capital-protecting constitution that could withstand the end of the dictatorship. Even with both of those data points, I don’t think I could have gleaned the full import of his project had I not moved to North Carolina in 2010, where a strategy informed by his thought has been applied with a vengeance by the veto-proof Republican legislative majority that came to power in the midterms that fall. After Buchanan died in 2013, I was able to get access to his private papers at George Mason University, where the documentation is incontrovertible.

In fact, Buchanan’s records provided a kind of birds-eye view into collaboration between the corporate university and right-wing donors that at least I have never seen before, and I’ve done a lot of research in this area over the last two decades.

How would you draw a line connecting Buchanan to the Koch brothers?

Charles Koch supplied the money, but it was James Buchanan who supplied the ideas that made the money effective. An MIT-trained engineer, Koch in the 1960s began to read political-economic theory based on the notion that free-reign capitalism (what others might call Dickensian capitalism) would justly reward the smart and hardworking and rightly punish those who failed to take responsibility for themselves or had lesser ability. He believed then and believes now that the market is the wisest and fairest form of governance, and one that, after a bitter era of adjustment, will produce untold prosperity, even peace. But after several failures, Koch came to realize that if the majority of Americans ever truly understood the full implications of his vision of the good society and were let in on what was in store for them, they would never support it. Indeed, they would actively oppose it.

So, Koch went in search of an operational strategy — what he has called a “technology” — of revolution that could get around this hurdle. He hunted for 30 years until he found that technology in Buchanan’s thought. From Buchanan, Koch learned that for the agenda to succeed, it had to be put in place in incremental steps, what Koch calls “interrelated plays”: many distinct yet mutually reinforcing changes of the rules that govern our nation. Koch’s team used Buchanan’s ideas to devise a roadmap for a radical transformation that could be carried out largely below the radar of the people, yet legally. The plan was (and is) to act on so many ostensibly separate fronts at once that those outside the cause would not realize the revolution underway until it was too late to undo it. Examples include laws to destroy unions without saying that is the true purpose, suppressing the votes of those most likely to support active government, using privatization to alter power relations — and, to lock it all in, Buchanan’s ultimate recommendation: a “constitutional revolution.”

Today, operatives funded by the Koch donor network operate through dozens upon dozens of organizations (hundreds, if you count the state and international groups), creating the impression that they are unconnected when they are really working together — the state ones are forced to share materials as a condition of their grants. For example, here are the names of 15 of the most important Koch-funded, Buchanan-savvy organizations each with its own assignment in the division of labor: There’s Americans for Prosperity, the Cato Institute, the Heritage Foundation, the American Legislative Exchange Council, the Mercatus Center, Americans for Tax Reform, Concerned Veterans of America, the Leadership Institute, Generation Opportunity, the Institute for Justice, the Independent Institute, the Club for Growth, the Donors Trust, Freedom Partners, Judicial Watch — whoops, that’s more than 15, and it’s not counting the over 60 other organizations in the State Policy Network. This cause operates through so many ostensibly separate organizations that its architects expect the rest of us will ignore all the small but extremely significant changes that cumulatively add up to revolutionary transformation. Gesturing to this, Tyler Cowen, Buchanan’s successor at George Mason University, even titled his blog “Marginal Revolution.”

In what way was Buchanan connected to white oligarchical racism?

Buchanan came up with his approach in the crucible of the civil rights era, as the most oligarchic state elite in the South faced the loss of its accustomed power. Interestingly, he almost never wrote explicitly about racial matters, but he did identify as a proud southern “country boy” and his center gave aid to Virginia’s reactionaries on both class and race matters. His heirs at George Mason University, his last home, have noted that Buchanan’s political economy is quite like that of John C. Calhoun, the antebellum South Carolina US Senator who, until Buchanan, was America’s most original theorist of how to constrict democracy so as to safeguard the wealth and power of an elite economic minority (in Calhoun’s case, large slaveholders). Buchanan arrived in Virginia just as Calhoun’s ideas were being excavated to stop the implementation of Brown, so the kinship was more than a coincidence. His vision of the right economic constitution owes much to Calhoun, whose ideas horrified James Madison, among others.

And from that kind of thought, Buchanan offered strategic advice to corporations on how to fight the kind of reforms and taxation that came with more inclusive democracy. In the 1990s, for example, as Koch was getting more involved at George Mason, Buchanan convened corporate and rightwing leaders to teach them how to use what he called the “spectrum of secession” to undercut hard-won reforms through measures that have now become core to Republican practice: decentralization, devolution, federalism, privatization, and deregulation. We tend to see the race to the bottom as fallout from globalization, but Buchanan’s guidance and the Koch team’s application of it through the American Legislative Exchange Council and the State Policy Network reveals how it is in fact a highly conscious strategy to free capital of restraint by the people through their governments.

Another way all this connects, indirectly, to oligarchic racism: wanting to keep secessionist thought alive for this practical utility, the billionaire-backed right necessarily gives comfort to white supremacists. A case in point: the Virginia governors who supported the Buchanan-Koch enterprise at George Mason University also promoted a new “Confederate History and Heritage Month.” Likewise, the Ludwig von Mises Institute, which honors one of Koch’s favorite Austrian philosophers, is located in Alabama and led by Llewellyn Rockwell, Jr., a man who has long promoted racist neo-Confederate thought, yet was still thought fit to run the Koch-funded Center for Libertarian Studies. It’s thus a mistake to imagine that the Koch and so-called alt-right causes are wholly separate; there’s a kind of mutual reinforcement if you understand what Koch learned from Buchanan and how they operated.

As I conclude in the book, as bright as some of the libertarian economists were, their ideas gained the following they did in the South because, in their essence, their stands were so familiar. White southerners who opposed racial equality and economic justice knew from their own region’s long history that the only way they could protect their desired way of life was to keep federal power at bay, so that majoritarian democracy could not reach into the region. The causes of Calhoun, Buchanan and Koch-style economic liberty and white supremacy were historically twined at the roots, which makes them very hard to separate, regardless of the subjective intentions of today’s libertarians.

What would a society based on Buchanan’s principles and goals look like?

Tyler Cowen, the economist who co-presides with Charles Koch over the cause’s academic base camp (yes, that Tyler Cowen, host of the most visited academic economics blog), has spelled that out. You might want to sit down to hear what he envisions for the rest of us. He has written that with the “rewriting of the social contract” underway, people will be “expected to fend for themselves much more than they do now.” While some will flourish, he admits, “others will fall by the wayside.” Since “worthy individuals” will manage to climb their way out of poverty, “that will make it easier to ignore those who are left behind.” And Cowen didn’t stop there. “We will cut Medicaid for the poor,” he predicted. Further, “the fiscal shortfall will come out of real wages as various cost burdens are shifted to workers” from employers and a government that does less. To “compensate,” this chaired professor in the nation’s second-wealthiest county advises, “people who have had their government benefits cut or pared back” should pack up and move to lower-cost, poor public service states like Texas.

Indeed, Cowen forecasts, “the United States as a whole will end up looking more like Texas.” His tone is matter-of-fact, as though he is reporting the inevitable. Yet when one reads his remarks with the knowledge that he has been the academic leader of a team working in earnest with Koch for two decades now to bring about the society he is describing, the words sound more like premeditation. For example, Cowen prophesies lower-income parts of America “recreating a Mexico-like or Brazil-like environment” complete with “favelas” like those in Rio de Janeiro. The “quality of water” might not be what US citizens are used to, he admits, but “partial shantytowns” would satisfy the need for cheaper housing as “wage polarization” grows and government shrinks. Cowen says that “some version of Texas — and then some — is the future for a lot of us” and advises, “Get ready.”

You conclude your book ironically with a Koch maxim: “playing it safe is slow suicide.” How does that apply to those who support a robust, non-plutocratic society?

I ended the book that way because I understand the many pressures that lead people not to act on their anxiety over what they are seeing unfold in Washington and so many states. Union leaders have fiduciary responsibilities that make bold action risky. Nonprofits have boards of directors to answer to. Young faculty must earn tenure. People in public institutions worry about their next appropriations. Parents have to budget their time. And so on. We tell ourselves, “Well, if it were that serious, surely others would be doing something about it.” So, I wanted to alert people that what is happening now is radically new — and designed to be permanent. We may not get another chance to stop it.

Buchanan and Koch came up with the kind of strategy now in play precisely because they knew that the majority, if fully informed, would never support what they seek.

Having said that, though, I also believe that panic is the last thing we need. There is great strength to be found in the simple truth that Buchanan and Koch came up with the kind of strategy now in play precisely because they knew that the majority, if fully informed, would never support what they seek. So, the best thing that those who support a robust, non-plutocratic society can do is focus on patiently informing and activating that majority. And reminding all Americans that democracy is not something you can just assume will survive: It has to be fought for time and again. This is one of those moments.

Truthout Is Preparing to Meet Trump’s Agenda With Resistance at Every Turn

Dear Truthout Community,

If you feel rage, despondency, confusion and deep fear today, you are not alone. We’re feeling it too. We are heartsick. Facing down Trump’s fascist agenda, we are desperately worried about the most vulnerable people among us, including our loved ones and everyone in the Truthout community, and our minds are racing a million miles a minute to try to map out all that needs to be done.

We must give ourselves space to grieve and feel our fear, feel our rage, and keep in the forefront of our mind the stark truth that millions of real human lives are on the line. And simultaneously, we’ve got to get to work, take stock of our resources, and prepare to throw ourselves full force into the movement.

Journalism is a linchpin of that movement. Even as we are reeling, we’re summoning up all the energy we can to face down what’s coming, because we know that one of the sharpest weapons against fascism is publishing the truth.

There are many terrifying planks to the Trump agenda, and we plan to devote ourselves to reporting thoroughly on each one and, crucially, covering the movements resisting them. We also recognize that Trump is a dire threat to journalism itself, and that we must take this seriously from the outset.

Last week, the four of us sat down to have some hard but necessary conversations about Truthout under a Trump presidency. How would we defend our publication from an avalanche of far right lawsuits that seek to bankrupt us? How would we keep our reporters safe if they need to cover outbreaks of political violence, or if they are targeted by authorities? How will we urgently produce the practical analysis, tools and movement coverage that you need right now — breaking through our normal routines to meet a terrifying moment in ways that best serve you?

It will be a tough, scary four years to produce social justice-driven journalism. We need to deliver news, strategy, liberatory ideas, tools and movement-sparking solutions with a force that we never have had to before. And at the same time, we desperately need to protect our ability to do so.

We know this is such a painful moment and donations may understandably be the last thing on your mind. But we must ask for your support, which is needed in a new and urgent way.

We promise we will kick into an even higher gear to give you truthful news that cuts against the disinformation and vitriol and hate and violence. We promise to publish analyses that will serve the needs of the movements we all rely on to survive the next four years, and even build for the future. We promise to be responsive, to recognize you as members of our community with a vital stake and voice in this work.

Please dig deep if you can, but a donation of any amount will be a truly meaningful and tangible action in this cataclysmic historical moment.

We’re with you. Let’s do all we can to move forward together.

With love, rage, and solidarity,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy