Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

I can’t quite remember when I turned against the idea of war, but I’m sure it had something to do with the fact that I didn’t want to die. From pretty much the sixth grade on, I was firmly, solidly, against dying.

But up until then, I spent many years dying with verve in our neighborhood. The favorite game to play on our street was War. It beat Bloody Murder by a mile because it had weapons. Bloody Murder was really just a game of hide-and-seek (when you found the person hiding, you would yell “Bloody murder!” and everyone would try to make it back to touch the home pole before those who were hiding could tag you).

War was the real deal – and girls couldn’t play. The rules were simple. A group of boys, ages four to ten, would divide up into two groups: the Americans and the Germans. We each had our own set of toy machine guns, rifles, and bazookas. I was much admired for my fine stash of hand grenades that came complete with the pin you could pull out as you tossed it, accompanied by a very loud “explosion” that would come out of my mouth.

None of us minded whether we were chosen to be a German or an American – we already knew who was going to win. It became less about winning and more about coming up with creative and entertaining ways to kill and be killed. We studied Combat and Rat Patrol on TV. We asked our dads for ideas but none of us got much help as they didn’t seem to want to talk about their war experiences. We all imagined our fathers as well-decorated war heroes, and it was just assumed that if we ever had to go to war we would be every bit the brave defenders of freedom they were.

I was particularly good at dying, and the other kids loved machine-gunning me down. Especially if I was playing a German; I’d stand for as long as I could, taking as many of their bullets as I could, and, long before Sam Peckinpah arrived on the scene, I was going down in a slow-motion agony that gave all the other boys a thrill for offing my sorry Nazi ass. And when I hit the ground, I’d roll over a couple times and, in a fit of spasms, I would expire. As I lay there, eyes open, motionless, I felt a strange sense of satisfaction that I played an important role in seeing one more nasty Nazi bite the dust.

But when I played an American, I would try to stay alive as long as possible. I would find some way to sneak in behind enemy lines, hide in a tree, and then take out as many of the Germans as I could. I especially loved lobbing the grenades from above; it was so upsetting to the “Nazi” boys who could not figure out where all these little bombs were coming from. I would make sure to leave one or two of them alive so they could shoot me. Then I could die a hero’s death, cut down in my prime, maybe taking one last “Nazi” with me as I fell on them, pulling the pin off my final grenade, blowing both of us to bits as we hit the ground.

But by 1966, as the pictures on the evening news seemed nothing like what we were acting out on our little dirt street, “playing” war became less and less fun. These soldiers on TV were really dead – bloody and dead, covered in mud, then covered by a tarp, no slow-motion heroics provided. The

soldiers who remained alive, they looked all scared and disheveled and confused. They smoked cigarettes, and not one of them looked like he was having much fun. One by one, the boys in the neighborhood put away their toy guns. No one said anything. We just stopped. There was homework and chores to do, and girls seemed distantly interesting. The Americans won The Big War That Counted, and that was enough.

By the summer after seventh grade our family left the dirt street and moved on to a paved one – the very street that we lived on when I was born. I started to think a lot about the Vietnam War that summer, and most of what I thought about wasn’t good. I did the math and I realized I was just five years away from draft age! And it was becoming clear that this war was not going to be over anytime soon.

Mrs. Beachum was our afternoon lay teacher in eighth grade. Because our nun was also the Mother Superior for the school, she taught us only in the morning. Her afternoons were spent on her administrative duties and doling out the necessary disciplinary measures to the fallen ones among us.

Mrs. Beachum was black. There were no other teachers and only three black kids in the entire school – and perhaps because their last name was JuanRico, we somehow convinced ourselves they weren’t really black, probably Cuban or Puerto Rican! One of the boys was called Ricardo and the other was named Juan. See – not Negro! They were popular, and their parents were at every event helping out in any way that they could.

But Mrs. Beachum was definitely black. There was no getting around it. Her skin was nearly as dark as coal, and she spoke in a Southern dialect none of us were familiar with. Not a day would pass where she wouldn’t say to one of us in her distinctive Southern black accent, “Don’t be facetious, child!” We had no idea what that meant, but we just loved the sound of it. She had a body that was not covered by a nun’s habit, and I would not be surprised if, in 1967, I wasn’t the only boy in our class whose first “dream” had the good fortune of Mrs. Beachum playing a significant role in it.

But in our waking hours we did not sexualize her, as none of us wanted to deal with that in the confessional booth. Plus, the Mother Superior kept a strict and watchful eye on our puberty and its progress, and she made sure to spend time reminding each gender in the class just how much we could trust the other gender – which was, to put it simply, not a lot. Since fifth grade, the two genders of our class did their best to put down or ridicule each other, and by the time we were thirteen or fourteen, we had developed enough of a vocabulary and a streak of meanness to slice and dice the opposing side with plausible gusto. The girls were most fond of pointing out the boys who had hygiene issues, and they would anonymously leave a can of Ban deodorant on the locker of the offending boy for all to see. The boys had already picked up on the girls’ sensitivity to their growing (or not-so-growing) breasts. One boy had swiped his older sister’s falsies and they were thus left on the desks of those girls who had failed to blossom rapidly enough to match the ones we saw in Mike McIntosh’s Playboys.

This was how we spent our mornings in eighth grade, fighting back the heat inside with some church- sanctioned cool cruelty – all done with the good intention, I am sure, to keep us out of trouble and way out of wedlock.

After lunch, though, it was all jazz.

Mrs. Beachum would have none of this “boys versus girls” stuff. She believed in “love” and “being in love,” and though we couldn’t quite put our finger on it, years later we knew she was also the only teacher in the school making love (or so we wanted to think). When she taught us history, she made the characters come alive.

“What do y’all know about Teapot Dome!” she’d say, never meaning it as a question. We had no thoughts about Teapot Dome, but we knew we were going to hear a sassy story about it.

“Warren G. Harding — uh-huh! He sure was sumpin’! Scandal? Lordy, he wrote the book on it!”

Every class was like this.

“Lemme hear some sweet poetry today, children! Who’s written a poem just for me?” Oh, believe me, we were all writing poems. She had us rhyming and she taught us rhythms, and sometimes she would take our poem and sing it back to us. Every once in a while, the Mother Superior would stick her head in to see what was going on. She didn’t object, just as long as the boys were still sitting on one side of the room and girls were on the other. Her tacit approval of Mrs. Beachum’s methods made us less worried for her, and it relaxed the room to the point where on the day Mrs. Beachum proposed her Big Idea, there was surprisingly little objection among us.

“I think it’s time to teach y’all a little manners! You ever hear of ‘etiquette’?”

We had heard of it but certainly had never been practitioners of it.

“Well, boys and girls, I think it’s time we all went out to dinner with each other and learn how proper people do things! Boys, I want you each to pick a girl to be your dinner partner. Then for the next three weeks we’ll all learn proper table manners. When we’re ready, we’ll go to Frankenmuth for one of those famous fried chicken dinners!”

Of course, what she had in mind wasn’t “learnin’ manners” or “etiquette.” She was going to teach us how to date. I’m sure she had to sell this idea to the authorities without saying the word date, and I guess they saw nothing wrong with us knowing which one was the salad fork and understanding how the releasing of toxic gasses during a meal was not how God expected us to enjoy the fruits of his earth.

The twenty-seven of us in Mrs. Beachum’s class had just been told that nature’s gates could now be opened. For a few minutes we all giggled and twitched and – and, dang, we liked this idea! It was remarkable how quickly we each took to this concept of “going out” with someone else in the classroom who didn’t have our specific reproductive organs. (In years hence, I’ve wondered what this must have been like for the nonheterosexuals in the room – finally a chance to acknowledge sexual feelings! – but, damn! With the wrong gender! For them, I guess, it became an early lesson in faking it.)

The proper order of the world fell into place quite perfectly as each boy in the room rushed over to ask out the girl who was “appropriate” for him. The basketball star asked out the softball whiz. The piano player asked out the dancer. The writer asked out the actress. The boy from the trailer park asked out the girl from the trailer park. The boy with the hygiene issues asked out the girl with the hygiene issues.

And I asked out Kathy Root. I’m not quite sure how to explain the matchup, but perhaps the easiest way is to say she was the tallest girl in the class and I was the tallest boy. For my part, I couldn’t have cared less about our height – I had not taken my eyes off her for the past three years. She had long tan legs and a constant smile and was truly nice to everyone. And she was whip-smart. She was the girl most of the other boys would be too afraid to ask out – including me – so she made it easy on me and came across the room to where I was, frozen and petrified at my desk.

“Well, I guess it’s you and me,” she said gently so that I wouldn’t collapse into my pants.

“Sure,” I responded. “Yeah. For real. It’ll be fun.”

And that was that. I had the catch of the room. The girl who in high school would be elected our homecoming queen was going to be my “date” at our “etiquette” dinner.

By the next afternoon, though, tragedy struck.

“Michael,” Mrs. Beachum called out to me in the hallway after lunch. “Can I have a moment with you?”

She led me to a corner so that no one could hear us.

“I just want you to know that you’re probably the only boy in the class to whom I could ask this favor.”

She had the most encouraging eyes. Her hair made it seem as if she were the fourth Supreme. Her lips . . . Well, I didn’t know much about lips at thirteen, but what I did know, now standing closer to her than I ever had before, confirmed to me that there were no more inviting lips than those that Mrs. Beachum carried with her.

The lips parted, and she began to speak.

“I’ve already talked to your date, to Kathy Root, and she said it was OK with her if it’s OK with you.”

Yes, go on. Please. Don’t let the twitch on the left side of my face distract you.

“There are thirteen boys and fourteen girls in the class. So all the girls have a date except Lydia.”

“Lydia” was Lydia Scanlon. “Lydia the Moron” was the name most of the boys in class called her. Lydia was the class cipher. No one sat by her, and even fewer knew anything about her. She never spoke, even when called on, and she hadn’t been called on since fifth grade. There is always that student or two whom the teachers have to decide whether to fish or cut bait – there are only so many minutes in the school day, and if they won’t talk, you have to move on and teach the others. Five years of working on her to participate were apparently enough, and so most of us didn’t even know she was still in our class, although she was there every single day, in the last seat in the row farthest from our reality.

Lydia’s Catholic schoolgirl uniform was ill fitting, most likely the result of having been worn by two or three other girls in the family before her. Her hygiene was said to be worse than a boy’s, and her hair was cut . . . well, at least she had access to a mirror while she was cutting it.

It was no surprise that not one boy had made a beeline to her to ask her to be his date.

“I need you to ask Lydia to be your date for the dinner,” Mrs. Beachum said.

“Huh?” was all I could mutter. There was an instant lump in my throat because she was asking me TO GIVE UP THE BRONZE-LEGGED FUTURE-HOMECOMINGQUEEN BEAUTY AS MY DATE! I had won the Gold Medal, and now I was being asked to give it back! Just like Jim Thorpe! You cannot do this!

Without saying any of the above, Mrs. Beachum could read it on my face.

“Look, honey, I know you wanted to go with Kathy – but I know you know that no one will ask Lydia, and there’s just sumpin’ not right ’bout that. She’s a nice girl. Just a little slow. Some people fast, some people slow. All God’s children. All. ’Specially Lydia. You know that, don’t you?”

“Yes, Mrs. Beachum.” Yes, I knew that, and I actually even believed it. But weren’t the longest tanned legs in the school also something worth believing in?

“I knew that would be your answer,” she said proudly.

“Couldn’t ask this of the other boys. No sir! Only you. Thank you, child.”

Ugh. Why not? Why not ask them? Why me?

“Plus, I figured seeing how you are thinking of going to the seminary next year, you won’t really need many of these ‘manners’ I’m teaching you, now will you?”

Apparently the Mother Superior had shared my thoughts about becoming a priest with Mrs. Beachum. And, of course, what use does a priest have for sex, much less “manners,” much less those pink-black engorged lips you’re using to hand me the worst news of my life?

“Sure. It’s fine. But what about Kathy?” I asked. Yes, what about Kathy? You’re not considering the grief she’s going to experience not being able to be my date!

“Like I said, I already talked to her. She was very happy to do this special thing for Lydia. Said you would be, too.”

I decided to give it one last shot. “But, but then Kathy will be all alone at the dinner!”

“No, child, here’s what we do. Lydia will sit across from you. Kathy will sit with the both of you, next to Lydia. So in a way, Kathy will still be there as sorta your date, too.”

Sorta. (This will become the story of my dating life. More later.)

“But you’ll officially be there with Lydia and you will pull her chair out for her and order for her and talk to her and make her feel that she, that she . . . is . . .”

A hint of tears began to make their way to the front of her eyes, but she blinked fast enough to catch them and wick them back behind her sockets and finished her sentence.

“That she is wanted. Can you do that, Michael?”

That this had suddenly been elevated beyond an etiquette lesson, beyond a date, to a call for mercy and possible sainthood – well, that was all I needed to hear.

“Yes, I can do this. I want to do this. You can count on me! You’re right, I won’t have any use for girls after this year anyways!” Exactly! Mrs. Beachum, you’d just be wasting all these lessons on me. I’m off to be a monk for life!

I had a pain in the pit of my stomach.

I went into the classroom and asked Lydia to be my date. Though I tried to say it soft enough so none of the other boys would hear me, it wasn’t long before word got out that I had given up the top prize for the Loser Lydia – and these little men in their high – waisted pants spent a lot of time on the playground scratching their butch-cut heads and trying to figure out exactly what had happened to me.

“Don’t make sense, Mike,” Pete said, shaking his head. “How are you even gonna stand it, being next to her?” “I dunno” was about all I could muster. How was I going to sit next to her? Ewww.

The big night came to go to Frankenmuth, and Lydia was all freshly scrubbed and her dress was plain but pretty. I opened the door for her, let her take my arm, pulled her chair out for her and, in a momentary act of rebellion against my impending lifelong celibacy, I pulled Kathy’s out for her, too. Kathy talked to Lydia, then I talked to Lydia, and Lydia talked back to us. We heard the story of how her brother had died and how her dad was working two jobs because her mother had health problems and how she spent her time in her room writing poems. Lydia was shy but not a cipher. She was funny, and she had a snorty laugh that after a while was cute and catchy. The other classmates looked down the table to see what the three of us were up to, and a couple of the boys joined in to talk to the newly interesting Lydia. This gave Kathy and me a chance to talk, also a new thing for me, for up until now she had just been an object to observe as often and as vigorously as possible.

“You were a good guy, Mike, to do this,” she whispered to me.

“Really? Um, well, you know I’m going to the seminary?”

“Sure. I heard that.”

“So, you see, this class wasn’t really for me.”

“Well, it was fun, don’t you think?”

“Sure. Can I have your pie if you’re not gonna eat it?”

After our class’s First Date Night at the Frankenmuth Bavarian Chicken House, there was no going back to the War of the Sexes. Thanks to Mrs. Beachum, we all discovered that we liked each other – a lot. And while others contemplated their next moves in the dating life, I had time to ponder such things as what kind of trouble would Mrs. Beachum be in for having upended the Puberty Retardation Policy that the Church had implemented. Boys stopped picking on girls, and girls stopped laughing at boys. We helped each other with homework. We let the girls throw the basketball around. Everything felt better and we were grateful to Mrs. Beachum for her enthusiasm and her desire to teach us more than just the capitals of all fifty states. We looked forward to our afternoons with her; it was the best part of every day. So when we came back from lunch for our afternoon with Mrs. Beachum on February 5, 1968, we were surprised to learn that she had not shown up to school. She did not show up the next day, either. Nor the next day. We were told that no one knew where she was, that she was missing. At first, we hoped that maybe she had overslept and just not shown up for work for a few days. The Mother Superior filled in for her. But as the week went on, the look of worry and concern on Mother Superior’s face was evident, and her attempts to follow Mrs. Beachum’s lesson plans were awkward, as she was surely distracted. She offered no information, and by the fifth day of Mrs. Beachum’s absence, enough of us had complained to our parents and asked them to please get to the bottom of just what the heck was going on.

The nightly news on TV that week was grisly. It was the Vietnamese New Year (“Tet”) of 1968, and though this was the first time any of us knew the Vietnamese got a second New Year, the only reason we knew this was by way of Chet Huntley and David Brinkley explaining to us why the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese had launched their biggest offensive of the war. NBC News was especially graphic (in those days, TV showed the war uncensored). Their camera caught a South Vietnamese general grabbing a Viet Cong suspect on the street, putting his gun to the man’s temple, and blowing his brains literally out of the other side of his head. That made the Swanson Salisbury Steak TV dinner go down easier.

The Tet Offensive of 1968 sent a shock wave through the American public because, opposite of everything we had been told about the United States soon “winning” the war – “We can see the light at the end of the tunnel!” – in fact, Tet showed just how powerful the other side was and how badly we were losing. The Viet Cong were all over Saigon, even at the door of the U.S. embassy. We were nowhere near to winning anything. This war was going to be with us for a very long time. I stared at the TV, and I was happy I was going to the seminary next year. If you were in the seminary, they couldn’t draft you. One more reason not to need Mrs. Beachum’s dating service.

Word eventually filtered through the parents that Mrs. Beachum had indeed vanished. There was no official word from the parish, but this much was said:

“Mrs. Beachum’s husband is missing in Vietnam and presumed dead. Nobody knows where Mrs. Beachum is, but she has probably left and gone home to be with her family.”

We never heard from Mrs. Beachum again. No one did. It was said she was too distraught to talk to anyone at St. John’s and, if she had, no one would have quite known what to say to her. Others said she had a complete nervous breakdown when she got the news about her husband and she went off, to be far, far away, to be by herself and shun this cruel world. One parishioner said she took her own life, but none of us believed that because if there was one person who was thrilled about being alive, it was Mrs. Beachum. We finished out the year with an afternoon substitute teacher who did his best, but he never asked us to sing him a poem.

It was then, in the spring of 1968, after the deaths in Vietnam of Sergeant Beachum and a boy from the high school, plus the assassinations of King and the sweet man in the Senate elevator who helped me find my mother, that I made up my mind: under no circumstances, regardless of whatever amount of coercion, threats, or torture leveled at me, I would never, ever, pick up a gun and let my country send me to go kill Vietnamese.

And if anyone would ever ask me why I felt this way, I’d just look at ’em and say, “Don’t be facetious, child.” Perhaps Mrs. Beachum is reading this. If so, I want to say: I’m sorry for whatever it was that took you away from us. I’m sorry we never had the chance to say good-bye. And I’m so sorry I never got to thank you for teaching me all those wonderful manners.

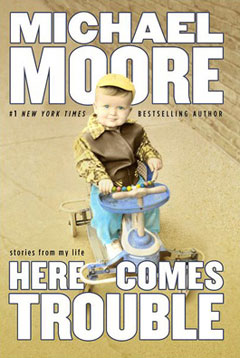

Copyright © 2011 by Michael Moore

Reprinted with permission from Grand Central Publishing.

Matching Opportunity Extended: Please support Truthout today!

Our end-of-year fundraiser is over, but our donation matching opportunity has been extended! All donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar for a limited time.

Your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. Your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. As Trump attempts to silence dissenting voices and oppositional nonprofits, reader support is our best defense against the right-wing agenda.

Help Truthout confront Trump’s fascism in 2026, and have your donation matched now!