Puebla, Mexico, 8 April 2018: An annual Easter march to shine a light on the plight of Central Americans living in a region with the highest murder rate in the world drew the attention of international aid groups, the United Nations … and the President of the United States. While the U.N. admonished the government of Mexico to provide safe conduct to the approximately 1,200 persons who crossed the southern border of their country, Donald Trump reacted with incommensurate fear, threatening to deploy National Guard troops to his own border, 1,200 miles (2,000 km) away.

The march, or caravan, is also known as the Via Crucis del Migrante (Migrant Stations of the Cross). A more-or-less yearly event, the caravan has been organized by Pueblo Sin Fronteras (People Without Borders), an NGO with a presence in Arizona, for over a decade. The original Via Crucis recalls the path Jesus Christ took to his execution according to the Christian religion: a fourteen-step journey that recounts the burdens, humiliations, consolations, torture and death he suffered, before being resurrected and ascending to heaven on what was to become Easter Sunday. In historically Catholic Central America, marking the Stations is a significant event.

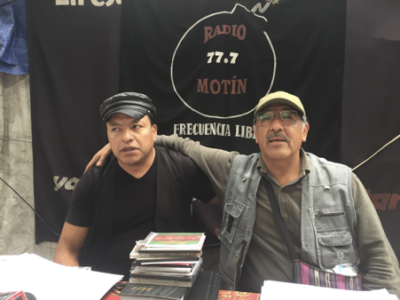

Usually numbering less than a hundred, Via Crucis del Migrante 2018 grew unexpectedly, according to organizer Irineo Mújica, though not unpredictably in retrospect. This year’s caravan has a high number of Hondurans, reflecting that country’s extreme levels of violence and deepening political crisis following a contested presidential election in November that resulted in widespread protests and “excessive use of force” in response.

The caravan is also mostly made up of women, children, unaccompanied minors and LGBTI persons, compelled to leave their homes but seeking the protection afforded by the organized march. According to Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), even hospitals in Honduras are dangerous for victims of gender-based violence because they cannot be guaranteed safety within. And the road through Mexico is fraught with danger for even the most able-bodied.

Violence is the main factor pushing Central American emigration. A Canadian professor attending a conference on comparative education in Mexico City’s historic centre says she no longer goes to El Salvador: “It’s too dangerous.” Discovery of trucks packed with Central Americans suffering and perishing from heat and thirst has become routine nowadays in Mexico, even occurring simultaneously with the march.

After a stay in Oaxaca, a smaller number of people from the caravan reached the city of Puebla on Thursday, with plans to continue on to Mexico City over the weekend. Along the way, individuals may apply for asylum or connect with relatives in Mexico, or take advantage of 20-day transit visas to press on to the U.S. border and take their chances there.

Even though Puebla State is highly industrialized and home to Volkswagen and Audi, times are tough for its residents. “Our patrols drive Jettas. But the minimum wage is 88.36 pesos a day,” explains Roberto, “and a cheap meal, nothing special, costs 150 pesos at least…. You can’t have a rich government with a poor population.”

Still, Mexicans in Puebla do not appear to be distressed by the arrival of the Central American caravan in their city. While Trump grandstands and stokes racist fear, and Mexico’s four presidential candidates declare a united front against U.S. retaliation, townspeople appear nonplussed. “They’re not doing any harm,” say University of Puebla students Saúl y Jesús, who were interviewing tourists in the town square, the Zócalo, for a class project, as the caravan left Oaxaca for Puebla.

Two days later, as the migrants gathered nearby, Marta and her colleagues at the reception desk of the Casa de Oración San José insisted that the caravan was nothing to fear. “They come every year. They are believers.”

According to an Amnesty International report published in January, the Mexican government deported 80,353 immigrants in 2017. AI conducted a survey and found that the majority of Central American immigrants into Mexico interviewed said they were not informed of their right to request asylum, and qualified their treatment by Mexican authorities as “bad” or “very bad.”

Why the focus on relatively small numbers of defenceless refugees by wealthier countries built upon immigration? Basilio Villagrón Pérez, who has been maintaining an encampment in front of the public prosecutor’s office in Mexico City in honour of 43 missing teacher’s college students from Ayotzinapa, explains it as “state terrorism against people who organize. The children of the indigenous and the campesinos are the most organized and always claim their rights in public protest.”

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Our fundraising campaign is over, but we fell a bit short and still need your help. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.