Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

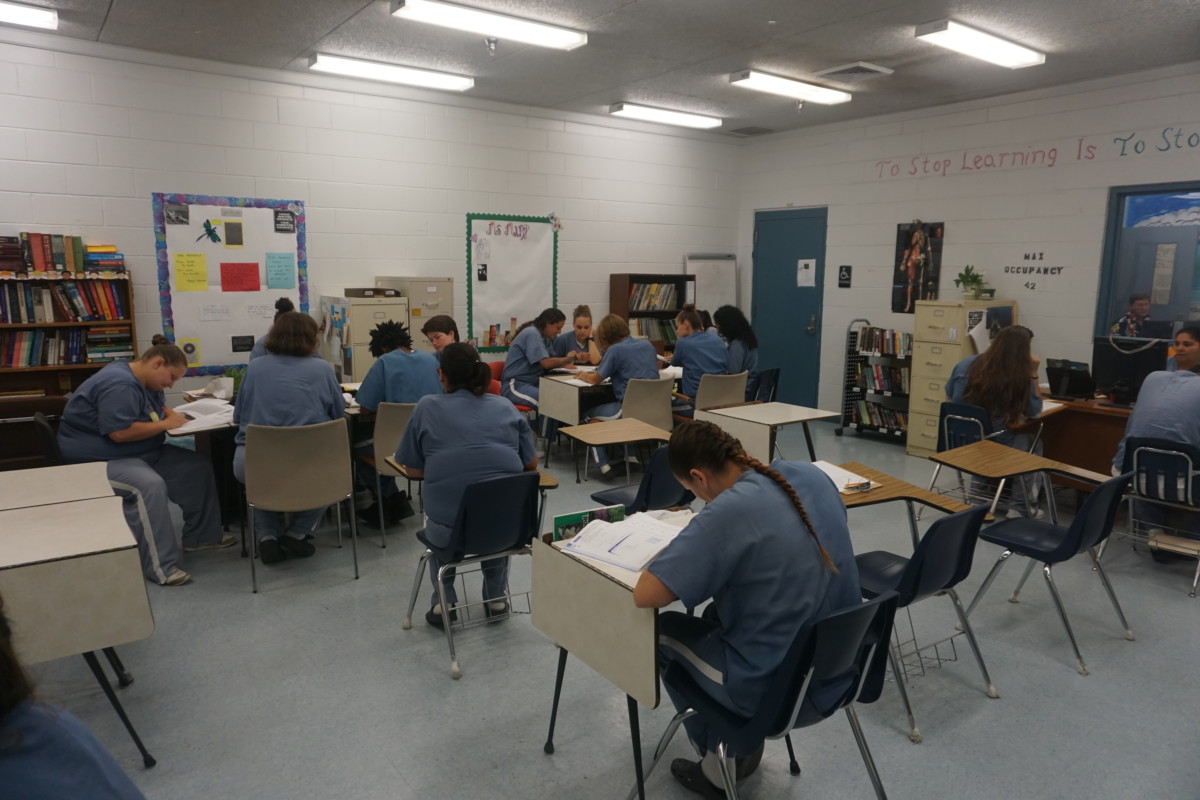

At Lowell Correctional Facility, a women’s prison in Ocala, Florida, incarcerated volunteers provide a literacy program to help fellow prisoners improve their reading capabilities. The facility is the largest women’s prison in the United States, housing roughly 2,600 prisoners.

Over the past few decades, several studies and reports have been published in an attempt to establish a sense of the literacy rates in prisons throughout the United States. Though data is sparse, the few studies conducted by the Department of Education and several other organizations point to a continuing issue within the criminal legal system: Many of those currently incarcerated find themselves struggling with the literary skills required to function in society.

“We test them to see where they are and get them ready for the GED. This is more involved one-on-one than the teaching in the GED program,” Mary Christensen, a prisoner volunteer tutor in the Lowell Correctional Facility program, told Truthout. “I have some students who test at a second-grade level, so it varies. There are some students in here who never completed kindergarten.”

Like many prison education programs, the literacy program at Lowell Correctional Facility is entirely run by volunteers, all of whom are prisoners. All correctional department programs in Florida combined only constitute 2.3 percent of the state prison budget, and Republican Gov. Rick Scott has proposed further cuts to education services for prisoners and parolees in the 2018-2019 fiscal year.

Lyndsey Overton, a student of the Lowell Correctional Facility tutoring program, graduated from an Ocala high school in 2005 with a special diploma, a type of high school diploma offered to students with a disability.

“I didn’t have the best teachers to help me, but I was struggling all through school my whole life,” Overton told Truthout. “I basically kept to myself. I had few friends.”

Now Overton is trying to prepare herself to obtain a GED. “I like to do puzzle books, the easy puzzle books,” she said. “I read my Bible more than any other books.” Overton hopes to be able to get a part-time job when she leaves prison. “I do not want to come back,” she added.

The latest Department of Education survey, conducted in 2014, found 29 percent of those incarcerated scored below level two out of five levels rating literary skills, compared to 19 percent among US household populations. The sample size of 1,546 reflected prison populations from 98 participating prisons across the United States.

“At Level 2, adults can integrate two or more pieces of information based on criteria, compare and contrast or reason about information, and make low-level inferences. They can navigate within digital texts to access and identify information from various parts of a document,” an author of the survey, Holly Xie, who is the program officer for the Assessments Division at the National Center for Education Statistics told Truthout in an email. “So, for example, they may be able to navigate to a ‘Contact Us’ page on a website when asked to identify the phone number of an event organizer.” Below this level, individuals likely won’t possess these basic literacy skills.

While serving a sentence of more than 17 years for a nonviolent drug offense, Clifford Spud Johnson started using writing to occupy his time as a healthy outlet to avoid trouble within prison, but found many of his fellow prisoners had trouble reading what he wrote.The surveys were conducted based on assessments created by the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). The PIAAC defines everyday literacy as “understanding, evaluating, using and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.” For many Americans currently incarcerated, those everyday literacy skills are lacking, and most correctional facilities aren’t equipped with necessary funding or adequate educational programs to develop these skills.

“When I passed out my work to prisoners to review … I learned that a lot of men struggled with literacy. It was new to me because literacy among adults, especially men who showed few weaknesses, is rarely discussed,” he told Truthout. Johnson was first published in 2005, and has written over a dozen books since. “My work is a catalog of urban stories of things I have either seen, heard or done.”

He found his work resonated with many of his fellow prisoners who struggled with literacy skills, as his stories were relatable to their backgrounds. While incarcerated, Johnson taught a class on story-writing and publishing. “The library is filled with a lot of books, but rarely do we have a chance to tell our own story or know a story of someone like me to show that anything is possible,” he said.

For prisoners, lacking these literary skills poses a substantial obstacle toward escaping the prison cycle. The Department of Justice has cited that prisoners who participate in correctional education programs are 43 percent less likely to return to prison.

Despite the drastic difference in costs between educating prisoners and incarcerating them, education programs directed toward prisoners remain substantially underfunded.

A 2016 report published by the Department of Education found over the last three decades, spending on prisons and jails has increased by triple the rate of spending on public education. According to Literacy New York, less than 10 percent of incarcerated individuals seeking adult education in the US are currently being served, as most states have long waiting lists.

“The waiting lists are really long in Illinois for adult education programs where prisoners need additional skills before they begin seeking out a high school diploma,” said Jennifer Vollen-Katz, executive director of the John Howard Association, an independent watchdog of correctional facilities in Illinois.

Between 2009 and 2012, prison education spending decreased by an average of 6 percent in each state, according to a study conducted by the RAND Corporation. “Education funding inside prisons in Illinois is definitely lower than it should be,” Vollen-Katz said. “We suffered a budget impact for a few years here, and the correctional programs suffered as a result of that.”

Meanwhile, several states have made literacy even less accessible behind bars, by banning specific books or book donations from nonprofits. Literacy skills are necessary for prisoners to take advantage of what education programs may be available to them, but the existence of programs aimed to help prisoners who struggle with reading are scarce and vary greatly depending on the prison.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.