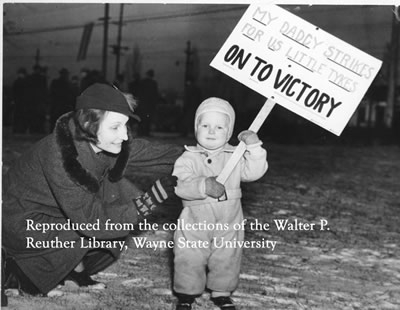

It began on December 30, 1936, at Fisher Body No. 1 in Flint, Michigan: workers occupied General Motors factories, launching one of the key struggles in U.S. labor history. A Women’s Emergency Brigade brought them food; when the police tried to drive out the strikers with tear gas, the women broke the windows to give them fresh air. After 44 bitter winter days, the sit-down strike forced GM to recognize their union, the United Auto Workers.

It was no accident that Flint was the scene of this historic battle. One hundred years ago, when the city boasted the largest factory in the world – a Buick plant – the people of Flint elected a socialist mayor. But GM founding partner Charles S. Mott won two years later, campaigning on a platform whose first point was “Only men who are successful at business should run city affairs.”

The 1936-1937 sit-down strike forced General Motors to recognize the United Auto Workers as the workers’ union.

The U.S. auto industry pioneered not only mass production but also mass consumption. “The American citizen’s first importance to his country is no longer that of citizen but that of consumer,” the pro-business Flint Journal editorialized in 1924. “Consumption is the new necessity.”

By the early 1950s, when I was a baby and my parents moved there, Flint’s workers were earning the highest industrial wages in the nation. In an exhibit called “Flint and the American Dream,” the city’s Sloan Museum displays the household belongings of a typical auto worker of the era: the kitchen appliances, formica countertops, and chrome-and-vinyl furniture, the lawn mower and charcoal grill of my childhood.

Abandoned houses pockmark the author’s old neighborhood.

Flint’s American dream is now a distant memory. Starting in the 1970s, one auto plant after another shut down, a downward slide vividly portrayed in Michael Moore’s film Roger & Me. In the 1981 recession, Flint had the highest unemployment rate in the country. Today, despite the fact that Flint’s population has fallen to less than 60% of what it was in 1960, the city’s unemployment rate still ranks in the top 20 among the country’s 372 metropolitan areas. In the neighborhood of company-built bungalows where I lived as a toddler, the pavements are cracked, the median strips overgrown with weeds, and abandoned, burnt-out houses decay amongst the surviving homes.

How did this reversal of fortunes happen?

The reasons behind Flint’s collapse are not only the greed and sheer ineptitude of General Motors’ management, memorably depicted in Roger & Me, but also monumental public policy failures. These include:

- massive foreign borrowing, an overvalued dollar and unprecedented trade deficits, beginning in the Reagan era, the fatal macroeconomic nexus that decimated American manufacturing;

- the failure to grow Medicare into a nationwide single-payer health care system, leaving U.S. firms – alone among those of advanced industrialized countries – saddled with employer-provided health insurance costs that further eroded their competitiveness; and

- racial divisions, “white flight” to the suburbs, and ill-conceived expressways that tore apart the social capital that was needed to mount an effective local response to these crises.

The grim result is that the American auto industry, which already had pioneered planned obsolescence in consumer goods, went a step further: Flint became a disposable city.

What can we learn today from Flint’s history? In hindsight, the consumption-based social contract espoused by the Flint Journal was not sustainable. It turns out that being a consumer is not a substitute for being a citizen. Caring about things is not more important than caring about each other. Private goodies are not a worthy substitute for public goods. Government cannot be entrusted safely to captains of industry. Our ability to consume cannot be detached from our responsibility to govern ourselves.

So Flint’s American nightmare teaches us this: When we elevate consumption above citizenship, we imperil not only our democracy, but in the end our economy, too.

James K. Boyce received his Ph.D. in economics from Oxford University. He is the author of Investing in Peace: Aid and Conditionality After Civil Wars (Oxford University Press 2002), The Political Economy of the Environment (Edward Elgar 2002), The Philippines: The Political Economy of Growth and Impoverishment in the Marcos Era (Macmillan 1993), and Agrarian Impasse in Bengal: Institutional Constraints to Technological Change (Oxford University Press 1987), and co-author of A Quiet Violence: View From a Bangladesh Village (with Betsy Hartmann, Zed Press 1983). He is the co-editor of Natural Assets: Democratizing Environmental Ownership (with Barry Shelley, Island Press 2003) and editor of Economic Policy for Building Peace: The Lessons of El Salvador (Lynne Rienner 1996). Professor Boyce’s current work focuses on strategies for combining poverty reduction with environmental protection, and on the relationship between economic policies and issues of war and peace.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.