Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

Pétion-ville, Haiti – Pink, green, blue, red. From a distance the thousands of brightly colored houses look like a painting. The observer can’t see the suffering and the dangers threatening the residents of the Jalousie neighborhood; suffering and dangers that are also being ignored by the government, which is spending US $6 million on a massive makeup job.

“Danger” because just last month, experts announced the hillside slum, home to 45,000 – 50,000 people, sits on a secondary fault.

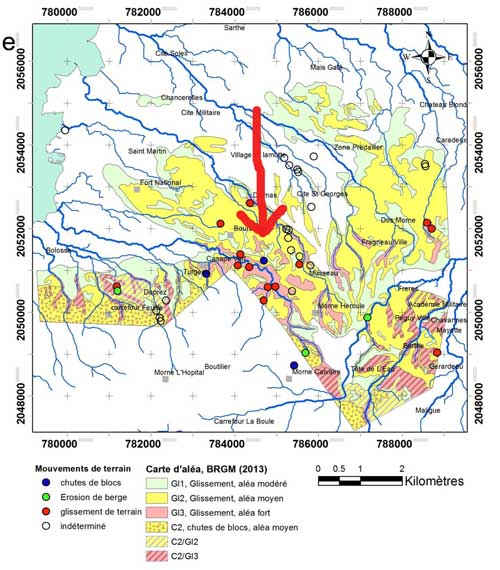

“Not only does a fault run through Jalousie, but there is also the serious danger of mudslides in the area,” geologist Claude Prépetit explained at a press conference on August 2, 2013. Prépetit was introducing a new seismological study of certain regions of Haiti’s capital region he recently coordinated.

A page from the recent seismologic “microzonage” study showing the areas at risk of mudslides.

A page from the recent seismologic “microzonage” study showing the areas at risk of mudslides.

Jalousie is also dangerous because many of the small houses have been built into the side of Morne L’Hôpital, on steep slopes or in ravines that serve as canals for rainwater. A recent government document notes that more than 1,300 homes should be moved because of they threaten both their residents and people living in the city below, given the frequency of mudslides during and after heavy rainstorms.

Jalousie residents are “suffering” because their neighborhood has no water system. Neighbors sometimes have to fight at the few water distribution points. Sanitation is also a problem for the almost vertical neighborhood where houses are linked by narrow stairways and alleys.

A recent study by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultral Organization (UNESCO) notes, “the population density may be as high as 1,800 people per hectare, and the living quarters range from eight to 30 square meters. Another aspect of this brutal scene is the fact that the 45,000 residents live in Pétion-ville, also home to most of the country’s wealthy neighborhoods. The social divideis striking. Massive mansions sit right next to the slum.”

Make-up to Mask the Misery and Dangers

The Michel Martelly government says it is in the process of spending over US$6 million on the slum, but not to deal with the double-danger or to provide services.

Instead, the administration is doing what some have called a “make-up job” – painting the houses in a project called “Jalousie en couleurs” (Jalousie in Colors), as homage to the Haitian painter Préfète Duffaut (1923-2012), who often filled his paintings with brightly colored hillside houses.

But a new coat of paint is not the top priority for residents, according to a mini-survey conducted by Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW). Asked what was most needed, 24 of 25 said they wanted schools for their children and one fourth added they wanted better access to water.

Just one year ago, the government announced it’s intention to destroy part of the neighborhood in a project called “Sove Lavi Mòn Lopital” (“Save Morne l’Hôpital”). The project aimed to knock down over 1,300 homes, reconstruct drainage canals and undertake other infrastructure improvements in order to protect the slopes and diminish the risk of mudslides and flooding.

Walls of water rush down the sides of Morne l’Hôpital – where officially it is illegal to construct or cut down any trees – during heavy rainstorms. Due to the lack of vegetation to hold it back, the mud can carry away people, animals and even entire houses. A wall of mud sometimes blocks the Union School, an Anglophone school affiliated with the US embassy and attended by the children of diplomats and the Haitian elite.

Image of Morne l’Hôpital from a Ministry of the Environment report.

Image of Morne l’Hôpital from a Ministry of the Environment report.

In May 2012, Minister of the Environment Ronald Toussaint explained “Operation Save Morne l’Hôpital” toLe Nouvelliste: “Morne L’Hôpital is a region that needs to be reforested in order to stop flooding downstream. We are also going to construct retention walls in the ravines, after the first demolitions. We will do this peacefully, be the government does not have any problems with the population.”

But the plan was suddenly cancelled after residents protested. [AlterPresse video here.] Rather than try to resolve the differences and misunderstandings, the government opted to fire Minister Toussaint and cancel the plan to move people out. Today, “Sove Lavi Mon Lopital” continues, but has been reduced to reforestation, infrastructure work and public information campaigns.

Protests vs. “Pride”

In spite of the difficult conditions, the threat from earthquakes and the possibility of mudslides, on August 16 the government announced Phase 2 of Jalousie en couleurs.

Phase 1, carried out at the end of 2012 and in early 2013, cost the government US$1.2 million and coincided with the inauguration of the Hotel Occidental Royal Oasis, a five-star establishment where a simple room costs US$175 and a “junior suite” runs more than US$350. The hotel faces the slum. Phase 1 assured 1,000 houses were painted, making the view a little more palatable.

“Phase 2 will be even bigger,” Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe told a hundred people gathered at the side of a soccer field at the August 16 inauguration. Lamothe said Phase 2 will cost US$5 million.

In his speech, Lamothe said 3,000 more homes would be painted and that the soccer field would get new stands, dressing rooms and synthetic turf. The prime minister also promised a 1.2 kilometer (less than one mile) asphalted street and the improvement of 2.8 kilometers of alleyways.

As Lamothe sang the praises of “Phase 2,” two dozen protesters with signs shouted: “We want water! We have not water” and “Schools!” and “We need a clinic!” [Télé-Kiskeya video here.]

Lamothe asked demonstrators to be “patient.”

“We’ll deal with all the problems little by little, but you know that you have many problems and we are trying to do a lot with little means,” Lamothe promised before leaving.

At least one resident – who, like most people questioned by HGW, said she would prefer to remain anonymous – is out of patience.

“What we need are water and electricity,” said a woman who lives in a small home with 11 others, including two children who do not attend school.

None of the beneficiaries surveyed by HGW were consulted regarding the choice of colors.

“Sure, we profited from a good initiative even though we didn’t get to pick out our color, but our needs are much greater than that. We can paint our houses ourselves,” said another resident.

For others, the coat of paint has no impact.

Doing laundry by hand on her little porch, one resident said she was not at home when the painting took place, and that she is not satisfied.

“I can paint my own house,” she said. “When I got home, I saw a bunch of splashes of paint on my wall.”

From afar the colors are striking. But for the houses not facing the hotel, the situation is contrary. And for all the houses, only the visible walls are being painted.

One Jalousie resident, Sylvestre Telfort, has the same opinion as many people here: the project is meant to cover the slum with a kind of make-up or greasepaint because it sits directly in front of the hotels Oasis and the new Best Western Premier.

On its Internet site, the Oasis promises its clients a “magnificent views of the city.” Best Western, where rooms run US$150 a night, tells its future visitors that the hotel is “located in the beautiful hills of Pétion-Ville, a well-known fashionable suburb of Port-au-Prince.”

“The project to paint Jalousie is nothing more than a social appeasement carried out be the government to satisfy the bourgeoisie who for years has tried to exterminate us, in vain,” Telfort said. “They can’t drop a bomb to eliminate people. So they have to took another tack and made colored the outsides our houses.”

The former minister of the environment is worried.

“The Morne l’Hôpital situation is chaotic. It’s a matter of public safety. Some 22 percent of residents of Pétion-ville live on Morne l’Hôpital, in Jalousie and Philippo. The concrete constructions prevent rainwater from seeping into the soil,” said former minister Toussaint. “Painting is not the answer.”

Claude Prépetit, coordinator of the seismologic study, is also concerned.

Many residents are in danger “because of the risk of mudslides and earth movements [and] the magnification of vibrations during an earthquake, because certain homes are built on a slope steeper than 30 percent, because it is near the southern peninsula and because a secondary faults cuts through it,” the geologist said.

Prépetit thinks the government should “interdict all future construction in the region” and “identify the more hazardous areas and move out everyone whose lives are at risk.”

As a last step, after assuring the population has social service, “they can paint the facades of the permitted houses, if they want to make them pretty,” he added.

During his visit to the slum, only 14 days after Prépetit and other experts announced the secondary fault, Prime Minister Lamothe made no mention of the seismic risks.

“You are going to see what we can do to improve people’s lives,” Lamothe promised. “Your will be proud! You will be happy!”

After his speech, Lamothe and his entourage got into an SUV to drive back down the mountain. Residents went back to their daily journeys, going up and down stairs to find water, trying to survive one more day in the slum called by Best Western “a fashionable suburb.”

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.