Part of the Series

Despair and Disparity: The Uneven Burdens of COVID-19

From politics to social media, Muslims or anything associated with Islam (whether correctly or not) are dehumanized as objects against which to measure the intensity or severity of all things negative and threatening. Such comparisons reinforce conscious and subconscious biases, and prime society and lawmakers to implement drastic and often repressive measures to address the latest perceived threat ostensibly posed by Muslims or Islam.

This cycle is nothing new. It should therefore come as no surprise that in the midst of the current pandemic, there is no shortage of examples of media, hashtags on Twitter, and lawmakers employing Islamophobia to foment panic and division by linking COVID-19 with Muslims and Islam.

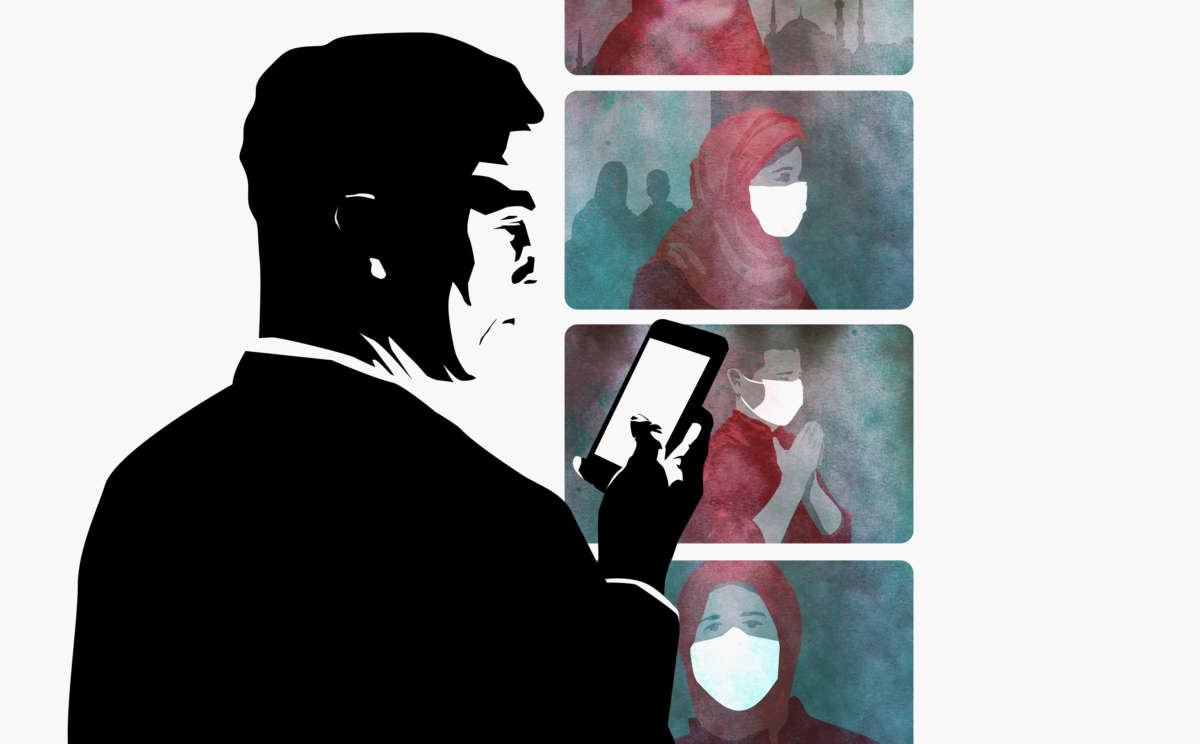

Screenshots of media headlines and headline images shared by users on Twitter offer a glimpse into the disconcerting use of images of Muslims or mosques that have nothing to do with the subject of the article. In countless news articles, images of Muslim men in congregational prayer and Muslim women wearing headscarves going about their daily business are paired with entirely irrelevant headlines ranging from shop closures in Italy to prisons in the U.S.

By constructing the specter of mass contagion out of the contrived criminality of Islam, the coupling of an image of a mosque with an article about U.S. prisons reinforces dangerous tropes that Islam is violent and suspect. It also flattens the extraordinary persecution that imprisoned Muslims — who are disproportionately Black Muslims — are subjected to, as well as the extreme danger that COVID-19 poses to all those currently incarcerated and detained.

The use of images of Muslims in Italy to accompany headlines about coronavirus is a perplexing choice, given the country doesn’t recognize Islam as a religion — despite there being 1.6 million Muslims in Italy (and only eight mosques). In fact, the ubiquity and near exclusivity of discussions involving Muslims in European public discourse in the context of threats to security (or in this case, public health) is telling. This became particularly evident when media outlets such as The New York Times, BBC and CNN International used images of Istanbul-based mosques for articles about the U.S. suspending travel from Europe due to the coronavirus. This, despite Turkey not being included on the list of banned European countries, and the so-called West’s typical reluctance to classify Turkey as anything remotely European.

These images convey subtle, indirect messages that link Muslimness and Muslim religiosity to panic around mass sickness, infection and deadly contagion. If you observed these offensively placed images in articles that had nothing to do with the subject of the image, and it didn’t particularly strike you as odd, inappropriate or even dangerous, you should ask yourself why. Perhaps it’s partly (only partly) because such discourse is just a small rhetorical step away from language that consistently sensationalizes Muslims as embodiment of the most extreme excesses of violence.

In addition to subtle, subliminal messaging linking COVID-19 to Islam and Muslims, major media outlets as well as anti-Muslim individuals are making direct, overt claims about the connections of COVID-19 with “extremism” and Muslims. “Extremism,” argues Richard McNeil-Willson, is just one of the many “politicized terms subject entirely to the government in charge at the time” and often associated with Islam and Muslims. McNeil-Willson describes how a piece in Foreign Policy medicalized “extremism,” as it argued for social media companies to take action against “extremist” content online in order to prevent those self-isolating from being “infected with disinformation.” Pathologizing “extremism” de-politicizes social and historical contexts and instead employs ableist and medically racist language that constructs political violence by Muslims in particular, as a “result of a malign mutation of an otherwise healthy body or cell in society.”

A tweet by a professor at Johns Hopkins University illustrated such a “mutation,” when he associated Muslims with an irrational mindset, stating, “Nothing will stop religious fanatics in Pakistan from making a bad situation even worse,” accompanying his tweet with a video that long preceded the pandemic. Similarly, an article published by the Canadian anti-Muslim organization Clarion Project identified “radicalization and extremism” as “viruses of global proportions,” and called on authorities to “diagnose them [radicals and extremists], isolate them and then treat them just like any other deadly virus until a cure is found.” Further, an Economist article recently generated criticism online after the headline equated Islam with an infection — a dangerous assertion given similar rhetoric has been used by the Chinese government to justify its imprisonment of up to 3 million Uyghurs, whom authorities state have been “infected” by an “ideological illness.” While recent think pieces have focused heavily on equating Islam with the COVID-19 pandemic, little attention has been paid to actual reporting from U.S. federal authorities that white supremacists have plotted bottling up infected saliva and spraying it at people of color.

Across the globe, the daily English language Indian newspaper, The Hindu, went even further by printing a political cartoon with the virus dressed up in clothing traditionally worn by Muslims in the region. Where there should be a head there is instead the image of the virus, illustrating an argument that has moved from comparison to direct equivalence: There’s no difference between a pandemic killing hundreds each day and a Muslim man wearing shalwar kameez — for the illustrator, they are one and the same.

For a plethora of overt displays of this fear-mongering, look no further than the right-wing Hindutva (Hindu supremacism) circles on social media. Anti-Muslim rhetoric and policies have been a mainstay of the current Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government under Narendra Modi, a Hindu nationalist administration which seeks to reconfigure India into a Hindu-only nation, leaving millions of Muslims and other marginalized groups vulnerable to second-class citizenship, deportation and violence. The state-led Islamophobia has trickled down to the public.

On Twitter, a viral hashtag has been dedicated to fearmongering about Muslims by equating them to the virus. #CoronaJihad is the latest in the long line of word formulations that “validate and naturalize Islamophobic interpretations that pervert the meanings of these terms by reducing them to slurs.” It’s not just limited to social media; the phrase has been promoted by Indian media itself in its efforts to spread disinformation and sow anti-Muslim hatred.

As op-eds in prominent media and a popular hashtag on Twitter have made direct, overt links around national security, Muslims and COVID-19, lawmakers in the U.S. have gone so far as to legislate the Muslim and African Ban in connection to the deadly global pandemic.

In early March 2020, the U.S. Congress was slated to vote on the National Origin-Based Antidiscrimination for Nonimmigrants Act, or “NO BAN Act” — a legislative attempt to end President Donald Trump’s discriminatory Muslim and African Ban, which was recently expanded in February 2020. This critical vote, however, was postponed after pressure from Republican lawmakers and the Trump administration in the wake of COVID-19. Such pushback directly linked the Muslim and African Ban to public safety and coronavirus, and has singled out Iran in particular. On March 10, House Minority Whip Steve Scalise (R-Louisiana) stated, “The president ought to be able to keep potential terrorists from coming into our country, but now with this outbreak of coronavirus, the president also needs to have all the tools available to limit, people coming in from countries with a high propensity of coronavirus.”

In a statement released March 10, the Trump administration itself linked COVID-19 to immigration restrictions on Muslims and Africans. The statement argued that the NO BAN Act would cause “dangerous delays that threaten the safety, security, and health of the American people,” and that “the President’s authority to restrict travel into the United States has been central to the Administration’s ongoing efforts to safeguard the American people against the spread of COVID-19.” This is rich coming from a president who has used racist and derogatory language linking public health to immigration restriction. Notably, in December 2017, Trump reportedly stated in an Oval Office meeting about immigration that Haitians “all have AIDS.” In the same meeting, he also reportedly singled out Nigerians (who were added to the Muslim and African Ban in February 2020), stating that they would never “go back to their huts.”

Given the global rise in far right and anti-Muslim politics, it’s only a matter of time before we observe increasingly explicit Islamophobic arguments by politicians and leaders much like the ones appearing online in rhetoric around COVID-19. We can rightfully conclude this from historic precedent. In other words, this isn’t new. Stoking fear and targeting marginalized communities — Asians, Muslims, Jews, immigrants and refugees, LGBTQIA2S+, poor, and disabled communities of color — is a tried-and-true tactic by politicians and the media. All too often in times of uncertainty and instability, pundits and politicians have preyed on people’s heightened emotions and fears, rhetorically scapegoating and passing laws and policies that target marginalized communities. As the global pandemic continues, we must push back against the affinity to construct Islam as a threat and Muslims as a contagion. Dangerous rhetoric that fans the flames of Islamophobia and further dehumanizes Muslims will only add to the ever-increasing global death count.

Note: Opinions expressed are solely the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of their employers. Thank you to Bridge Initiative Senior Research Fellow Nena Beecham for contributing background research that informed this article.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $29,000 in the next 36 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.