When Ryan Zinke was forced to resign from the Interior Department in December 2018, it was a conflict-of-interest scandal involving the chairman of oilfield services giant Halliburton that ultimately cost him his job. A foundation created by Zinke entered a real estate transaction with Halliburton’s David Lesar, prompting an inspector general investigation and pressure from the White House for Zinke to step down.

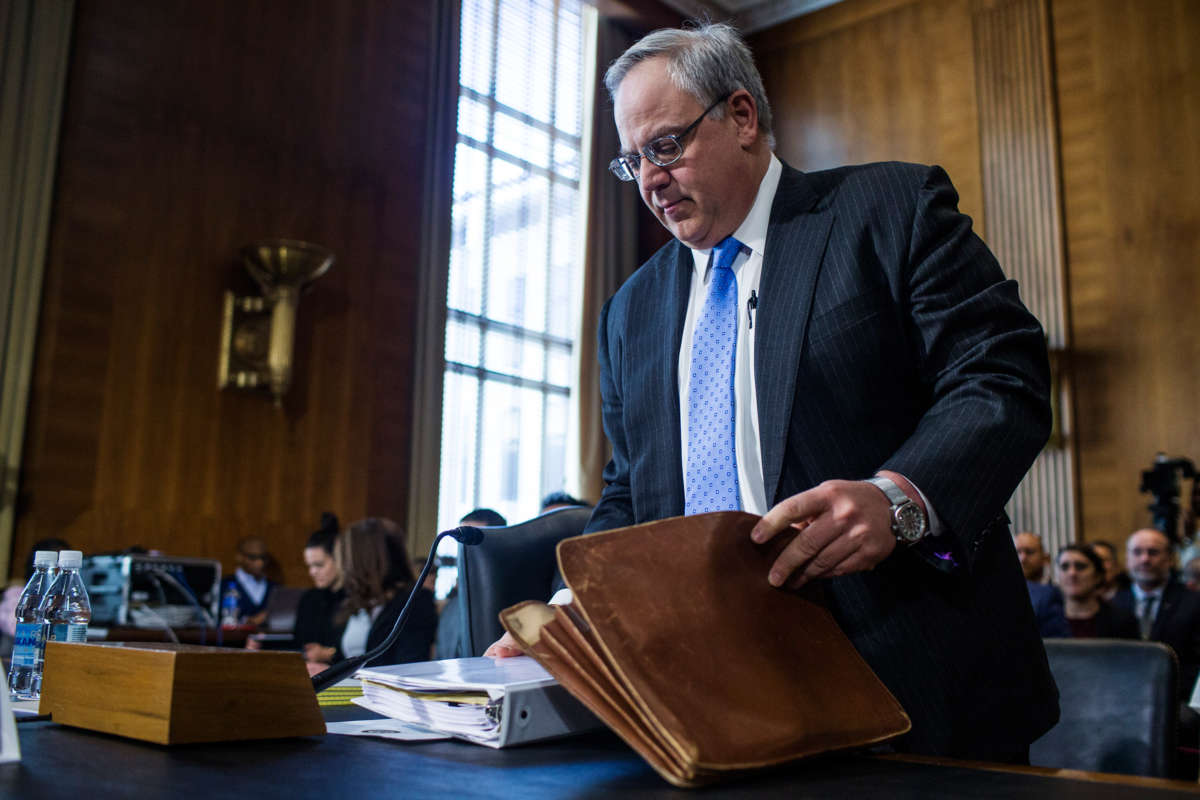

But Zinke’s replacement, David Bernhardt, has his own ethics issues involving Halliburton. From 2009-16, Bernhardt, was a lobbyist and attorney at Denver, Colorado-based Brownstein Hyatt Farber and Schreck, where his clients included dozens of oil, gas, and natural resources companies. Bernhard, who was confirmed as Interior Department secretary in April 2019, has so many potential conflicts from his work at the firm that he carries around a little card to remind himself of the companies he is supposed to avoid impacting as he goes about his job.

One of the companies on Bernhardt’s recusal card is Halliburton Energy Services, which, according to his financial disclosure, he provided legal services to from 2011 to 2013. Bernhardt agreed in his May 2017 ethics agreement to recuse himself until August 3, 2019 from matters involving specific parties in which Halliburton or several other entities are a party or represent a party to the matter.

A Sludge review of meeting logs compiled by Public Citizen and Documented Investigations found that during the period that Bernhardt was barred from meeting with Halliburton because of possible conflicts of interest, he met on several occasions with lobbying groups that represent the company.

Bernhardt met three times in 2017 and 2018 with representatives from the American Petroleum Institute, a lobbying group whose member companies include Halliburton and two other companies he is supposed to recuse himself from dealing with, Sempra Energy and Noble Energy. Halliburton paid the American Petroleum Institute $130,000 in membership fees in 2018.

Two of Bernhardt’s meeting with American Petroleum Institute officials were not disclosed on Bernhardt’s official calendar and were only discovered after researchers at Documented Investigations reviewed travel and visitor logs.

In November 2018, Bernhardt met with oil and gas industry lobbying group Western Energy Alliance. The group does not make its member companies public, but an archived copy of its website from 2016 shows that it represents Halliburton as well as Bernhardt’s old firm, Brownstein Hyatt Farber and Schreck. Bernhardt was a partner and shareholder at Brownstein Hyatt Farber and Schreck, where he led the natural resources division, until 2017.

Brownstein Hyatt Farber and Schreck reported lobbying the Interior Department for clients in 24 quarterly disclosures in 2019, according to a tally from the Center for Responsive Politics. The company’s 2019 clients include the American Petroleum Institute and several companies that Bernhardt had worked for, including the following: Hudbay Mineral, a Canadian mining company; Cadiz Inc., a Southern California water and agricultural resources public-private partnership; and Equinor, a Norwegian petroleum company with global operations.

The meetings do not technically violate Bernhardt’s recusal agreement, but Public Citizen’s Craig Holman told Sludge that Bernhardt’s ability to meet with groups representing clients on his recual list “can be easily abused to violate the spirit, if not the letter, of the recusal agreement.”

“It is not uncommon for a specific client or employer to use an association meeting as cover,” Holman said. “If the association meeting is between a small group and the public official, and the client or employer is present and uses the meeting for self-serving purposes, that would constitute a violation of the letter of the recusal agreement. But this is very hard to detect. Other times the agenda of the association is dominated by the same client or employer, so even if the client or employer is not present, the meeting would violate the spirit of the recusal agreement. But this is almost impossible to detect.”

Another oil industry group Bernhardt met with in 2018, Petroleum Association of Wyoming, has a Halliburton employee, Brian Carty, on its board of directors. The group, which describes itself as the “largest and oldest oil and gas trade organization in the state,”does not make its membership list public.

Bernhardt met with several other groups that do not disclose their members but likely represent companies on his recusal list, including Domestic Energy Producers Alliance and the Oil & Gas Endangered Species Act Coalition.

Halliburton reported spending $510,000 on lobbying the federal government in 2019. Altogether, the companies on Bernhardt’s recusal list spent nearly $30 million on lobbying the federal government from the beginning of the Trump administration through the third quarter of 2019, according to a Public Citizen analysis. The American Petroleum Institute was the sixth-largest oil and gas industry spender on federal lobbying last year with over $7 million in expenditures.

In 2018, the Interior Department initiated a process to open up nearly all U.S. waters to oil drilling, which is expected to increase offshore exploration and production activities and increase demand for digital oilfield services, a business in which Halliburton is a dominant player. The plan has been on hold for some time, but Bernhardt indicated in May 2019 that it is still moving forward.

Bernhardt’s history with Halliburton reaches back to a stint at the Interior Department during the George W. Bush administration. According to a copy of his Brownstein Hyatt Farber and Schreck bio, Bernhardt co-chaired the Interior Department’s Energy Coordination Council, which was in charge of implementing the Energy Policy Act of 2005. That bill contained a provision known as the “Halliburton Loophole” that exempted fracking companies from key environmental protection laws, allowing them to avoid disclosing information about the ingredients of their fracking fluids.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.