Part of the Series

Voting Wrongs

Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

In every election cycle since 1992, more than 30,000 people in Illinois have been denied the right to vote due to being confined in prison. Until 2019, an additional 19,000 were disenfranchised because they were in county jails. That year, however, Illinois passed two significant pieces of legislation that strengthened citizens’ access to vote.

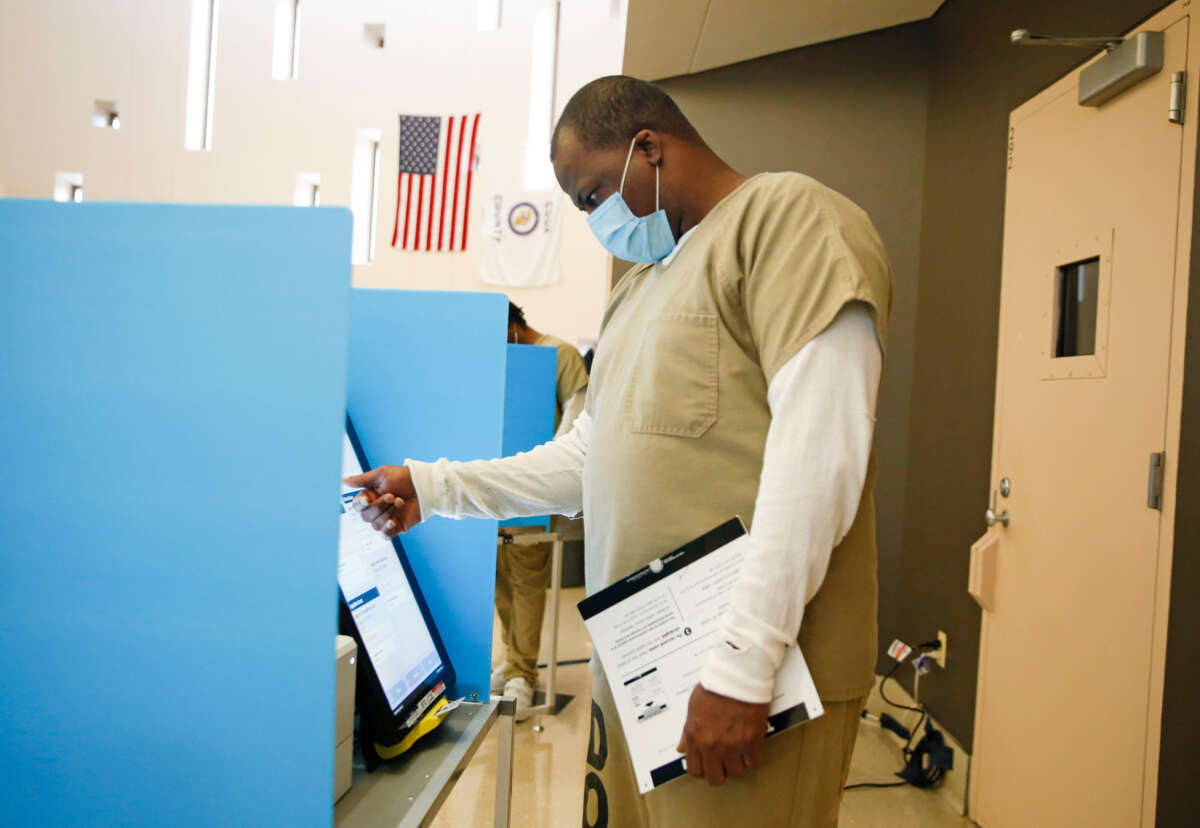

The “Voting in Jail” bill ensured that people who were being held in jail but not yet convicted of a felony could register and cast their ballots. The “Civics in Prison” bill required prisons to educate their incarcerated populations about the voting process, including that their right to vote would be immediately restored upon release.

When signing the “Voting in Prison” bill into law in 2019, Gov. J.B. Pritzker noted, “[W]e’re making sure that 20,000 people detained pretrial each year don’t miss out on the opportunity to have their voices heard.”

Today, Governor Pritzker and Illinois legislators have the opportunity to do the same for the 30,000 people who are incarcerated. The “Reintegration And Civic Empowerment (RACE) Act,” sponsored by Illinois State Sen. Lakesia Collins, would advance real public safety by re-enfranchising citizens who are imprisoned.

If passed, the RACE Act would accomplish two very important things. First, it requires mandatory voting education classes to be held at the beginning of a person’s sentence rather than prior to their release; and second, it allows people in prison to vote within weeks of beginning their sentence.

Illinois would not be the first state to allow people in prison to vote. Maine and Vermont currently do not disenfranchise incarcerated people. Some who are imprisoned in Alabama and Mississippi can vote, as well as all residents of Washington, D.C., even if they are held in the Federal Bureau of Prisons. (The “Inclusive Democracy Act,” which federal legislators introduced in 2023, would guarantee every incarcerated U.S. citizen the right to vote in federal elections.)

Currently, not a single person imprisoned by the Illinois Department of Corrections can vote. For about 4,300 of them who will likely die in prison, this effectively is a lifetime voting ban.

This wasn’t always the case. In 1970, well before mass incarceration would rear its ugly head, there were only 6,000 people imprisoned in the entire state of Illinois. None of them were sentenced to Life-Without-Parole or de facto life sentences. All of them — other than the handful sentenced to be executed — could become eligible for parole within a dozen years regardless of the crime they committed.

In the next few decades, Illinois would see the abolishment of parole (1978); Life-Without-Parole sentences (1978); automatic transfer of juveniles to adult court (1984); the Truth-in-Sentencing Act (1998); firearm enhancements (2000s), which required an additional 15 years to life in prison for any forcible felony committed with a firearm; and the Habitual Criminal Act (1978), among others. As a result of these inhumane sentencing policies, the prison population would reach 49,401 by 2013 — over eight times what it was in 1970.

The Chicago Police Department and Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office have long had a culture of misconduct that resulted in hundreds, if not thousands, of people being framed, wrongfully convicted, and sentenced to serve countless years (or the rest of their lives) in prison. We have countless cases of innocent people being exonerated after serving decades in prison. Experts agree that that is only the tip of the iceberg, and that many more remain incarcerated. The fact that they are denied their right to vote while in prison only increases the harm caused by the state. After all, there are no make-up votes once someone is exonerated.

(Many of the people confined to Illinois prisons, some of whom were wrongly convicted as well, were convicted for crimes as juveniles. In the 1980s, assisted by the false and hyperbolic claim that there was a coming hoard of juvenile superpredators, Illinois began automatically transferring juveniles arrested for certain crimes to adult court. There they received adult sentences, such as Life-Without-Parole and other lengthy prison terms that amount to de facto life sentences, all of which end up being lifetime voting bans as well.)

It should be obvious to everyone by now that demonizing, ostracizing and incarcerating people after they commit a crime does nothing to deter crime. Nor does disenfranchising them. Canada’s Supreme Court explained in 2002 that denying people in prison the right to vote “is more likely to send messages that undermine respect for the law and democracy than messages that enhance those values,” because “[t]he legitimacy of the law and the obligation to obey the law flow directly from the right of every citizen to vote.” The Court noted that “[t]o deny prisoners the right to vote is to lose an important means of teaching them democratic values and social responsibility.”

Way back in 1873, the famous suffragist Susan B. Anthony argued that the “moment you deprive a person of his right to a voice in the government, you degrade him (or her) from the status of a citizen of the republic to that of a subject … helpless, powerless… .” Cara Suvall, writing in the Rutgers University Law Review in 2022, quoted a CIRCLE study that found that “[i]interacting with the criminal justice system is one important way in which such a sense of powerlessness and antagonism to authority is generated.” Suvall found that “[w]hen youth voters feel disempowered, which they often do through criminalization generally and disenfranchisement specifically, they are less likely to vote.” Significantly, people who do vote when the right is restored upon release are less likely to end up back in prison.

The RACE Act now gives the Illinois General Assembly and governor the opportunity to take a giant step in restoring democracy by re-enfranchising people in prison and educating them about their right to vote earlier during their incarceration. As Suvall notes, “voting is habit forming — once a person votes, they are more likely to continue voting.” Encouraging participation in democratic processes will do more for public safety than disenfranchising people ever will.

The author thanks Mira Reddy for helping to assemble this article from messages sent on the prison messaging system.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.