A recent report by Saqib Bhatti of the Roosevelt Institute describes a number of financial deals between Wall Street and municipalities as predatory. Bhatti asserts that these dirty transactions have forced cities and states to cut essential services to pay off the financial sector. On Tuesday, Bhatti’s ReFund America project issued a new report specifically directed at the financial problems of Chicago and calling on the city to fight back in the courts and elsewhere against these deals.

One of the main problems arises from the use of interest rate swaps to create synthetic fixed rate municipal bonds. You’ll get great rates, cities were told, and these interest rate swaps will protect you against interest rate hikes. Risks were downplayed, if they were mentioned at all. The chief of these is the risk of downgrades in credit rating. In those cases, the swap could be cancelled, inflicting massive termination penalties on the city. Other risks include the inability to refinance into a lower interest rate, because the swap runs for a very long term, and payments would eat up any gains. Bhatti says the City of Oakland refinanced one of its bonds, and continues to pay for the swap; he says it’s “like paying for insurance on a car that was sold years ago”.

Another trap was the pension obligation bond. The idea is to borrow the money needed to make up a shortfall in pension payments, with the idea that the pension plan would invest the funds at a higher rate of return than the bond after expenses.

A third trap was Auction Rate Securities. These are short-term securities that have to roll over every month or two. If an investor in ARS wants out, but the city can’t roll the ARS over, the city is stuck with huge interest rate bills. This happened to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which saw interest rates jump from 4.3% to 20% in one week.

The Capital Appreciation Bond works just like a negative amortization home loan. The city doesn’t pay interest or principal for a few years, then starts paying the debt off, with interest on interest. Chicago and the Chicago Public Schools have a bunch of these, with lifetime interest rates ranging from 141% to 459%.

Municipal borrowings have traditionally been paid in full. Even so, far too many cities and school districts have been forced to pay for “credit enhancements” which are just the same as higher interest for no reason related to actual market conditions. On top of that, the two big municipal bond insurers were downgraded because of their exposure to toxic real estate mortgage-backed securities, and in order to avoid getting hammered by accelerated payment provisions in their bonds, cities were forced to find alternatives that were much more expensive.

Finally, the fees paid by municipalities are unusually high. There is no relationship between the services rendered and the fees, according to Bhatti.

The impact of these transactions on cities is horrifying.

For example, the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD) paid $547 million in termination fees to banks on its interest rate swaps in FY 2012. It has been estimated that more than 40 percent of Detroiters’ water bills now go toward paying down these termination fees. Fn. omitted.

In fiscal year 2013, Los Angeles paid $290 million in publicly-disclosed financial fees, while it cut services, including road repairs, by 19%. Other cities have similar horror stories.

The Obama Administration has completely ignored the plight of the citizens of these towns. From the outset Obama decided to help banks and creditors, the people who caused the Great Crash, and to ignore the staggering problems facing debtors. This became certain when the administration refused to support bankruptcy cramdown, one of the few steps that would have actually helped debtors, while inflicting losses on the lenders who made bad loans.

One crucial question is why more of these cities aren’t demanding better treatment. After all, they are run by politicians, who should be able to influence other politicians and other governmental agencies to help with the problems. But there was no pushback in Congress, and the administration did nothing to force financial industry regulators to help or even to investigate, despite reports of rampant fraud in the entire financial sector. Mayors and other local officials have simply refused to take action against the mistreatment of their towns and schools.

Thankfully, cities and school districts, like all parties to contracts, have a number of defenses to such contracts, despite the best efforts of the lawyers who wrote them for their clients in the financial sector. Bhatti mentions Rule G-17 of the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board, which requires banks and others suggesting transactions with public officials to “deal fairly” with them.

According to the MSRB, this means that they “must not misrepresent or omit the facts, risks, potential benefits, or other material information about municipal securities activities undertaken with the municipal issuer.”25 This means that they must ensure that public officials truly understand the risks of the deals they enter into and may not downplay the risks associated with those deals or mislead public officials about the likelihood of such risks materializing.

This suggests a plausible legal approach, either through enforcement actions by the SEC or litigation by cities and other governmental entities.

There are also contractural defenses at the state level. This is from a law journal article by Nancy Kim, Mistakes, Changed Circumstances and Intent.

The most common contract defenses are duress, unconscionability, incapacity, fraud, and the “basic assumption” defenses of mutual mistake, unilateral mistake, impossibility, frustration of purpose and commercial impracticability. Fn omitted.

The latter group is so named because in each case there has been “… a failure of a basic assumption material to the contract.” Let’s see how that would work with swaps. The City of Chicago recently terminated two swaps, after receiving this memorandum analyzing the situation from Swap Financial Group of New Jersey. Chicago entered swaps in 2002 with JPMorgan Chase Bank and Bank of America. The city sold variable interest rate bonds and entered the swaps to create a synthetic fixed rate combination of bond and swaps. The memo says that the combination was expected to deliver a lower interest rate than could have been achieved with a fixed rate bond by an estimated 1.145%. The costs to Chicago included something called a bank enhancement, which was estimated to cost 25 basis points.

As it turned out, the bank enhancement became expensive in the wake of the Great Crash, and the estimated savings over the fixed rate were about $1.4 million per year. Simultaneously, interest rates fell, and the swaps had a negative value of $35.5 million, representing the cost to terminate them. Meanwhile, the bond rating of the city dropped, at least partly due to the Great Crash, which makes it more expensive to refinance than it would have been years ago. The memo goes on to explain that it seems best for the city to terminate the swaps, and Chicago did. That wiped out all gains from the deal, without even taking into account the possibility that it could have refinanced the bonds at the very low fixed rates which have prevailed since the Great Crash.

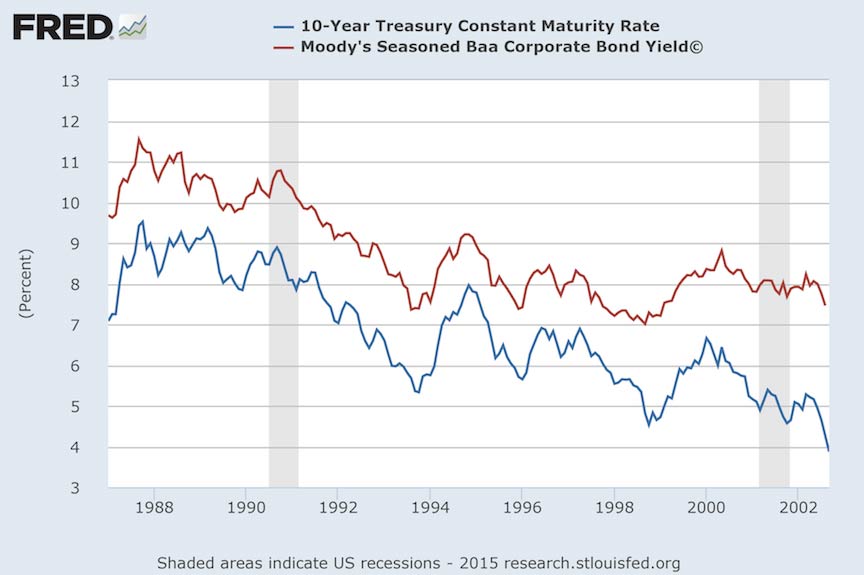

The parties to the swaps, JPM, BAC and Chicago, almost certainly shared the idea that interest rates would act in some historically normal way. That is, they might go up, they might go down, and there is some risk of a significant spike. Here’s a chart showing interest rate trends for the previous 15 years, for Treasuries and Baa rated corporate bonds.

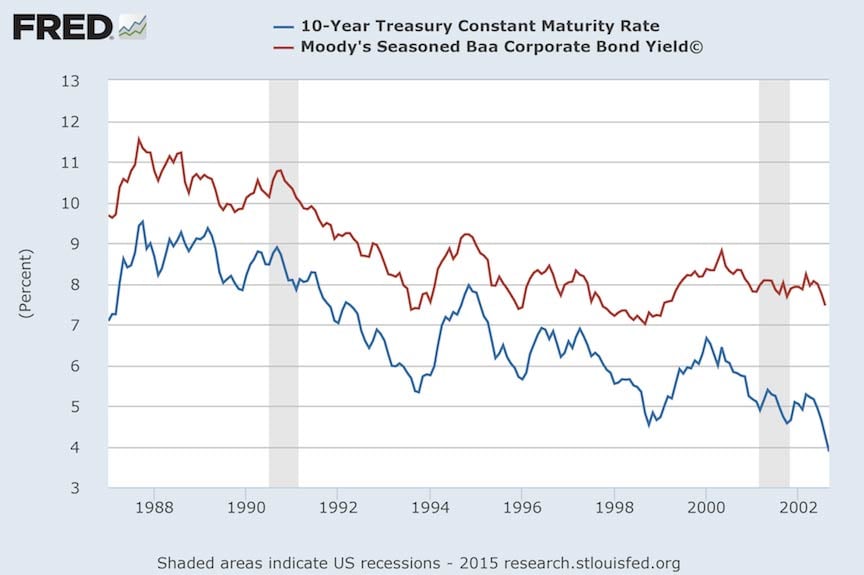

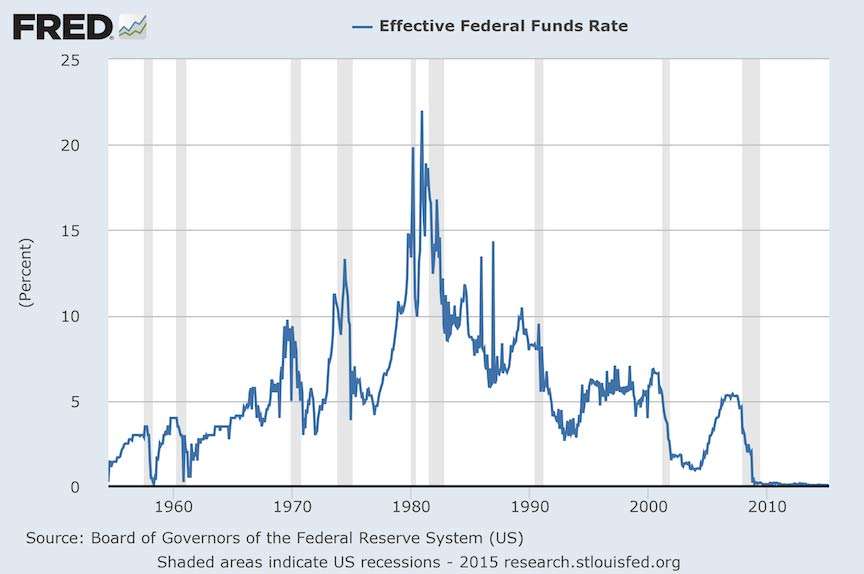

Interest rates are closely tied to the Fed Funds rate, and to people’s expectations about the interest rate policies of the Fed. Here’s a chart showing the Fed Funds rate since 1954.

That low rate beginning with the Great Crash hadn’t been seen in 40 years, and there are no periods when it was even constant for such an extended period. This qualifies as a stark variation from the historical pattern. This isn’t the place for a full legal analysis, but certainly a good case can be made that there has been a mistake in the deep assumptions of the agreements, or that there has been a frustration of purpose by the actions of the Fed in keeping interest rates so low for so long.

Kim cites an article by Richard Posner and Andrew Rosenfield, Impossibility and Related Doctrines in Contract Law: An Economic Analysis, 6 J. Legal Stud. 83, 1977. Posner discusses the application of the doctrine of law and economics to the same kinds of cases. One of his examples is a coal mining company that also makes coal-burning furnaces. It sells the furnaces with a contract to deliver coal at a stated price adjusted by the CPI. The price of coal quadruples, and the company defaults on delivery of the coal. Neither party could have contemplated such a sudden rise in price.

As Posner analyzes the case, the question should be which party is better equipped to deal with such a risk. He concludes that the coal company is best able to deal with the risk by hedging against big changes in the price of coal, because it knows its position in the coal markets. Therefore it should bear the loss. Whatever you think of the theory of law and economics, this seems like good analysis, because the sole purpose of the doctrine, like the facts of a swaps case, is economic efficiency. Kim’s more complex and more traditional analysis seems to support this result.

In the swaps case, it’s obvious that the banks were in the best position to protect against losses on these swaps. They are regular traders in these complex instruments, and have deeper insights into the interest rate markets and the various potential outcomes. Equally important, the banks bear heavy responsibility for the Great Crash. They were in the best position to prevent it. Chicago had no ability to do so.

For a somewhat different take, this paper, dealing with Canadian law, suggests that the appropriate considerations should include the doctrine of unjust enrichment, which is a principle of equity rather than contract law. Put simply, it means that a contract should not be allowed to inflict unreasonable harm “where the contract does not allocate the rick of the mistake to the party who suffers by it.” That certainly seems applicable here.

In each case, besides damages, a plausible remedy would be termination of the swaps without a termination fee. The Fed’s zero-interest rate policy increased the flow of money to the Banks at the expense of taxpayers, which is not a proper purpose and might not have even been considered or intended. The two banks benefited from payments for years, while taking no significant risk, because the Fed has forcibly kept interest rates down. At the same time, Chicago has has suffered revenue losses because of the Great Crash, and has been forced to cut services to its residents. Denying the termination fee prevents unjust enrichment, and results in at least a partial sharing of the risk of a zero-interest rate policy.

Bhatti and others are calling for the City of Chicago to take legal action. It certainly looks like there are grounds for a lawsuit, and if Chicago won’t do it, maybe your mayor should.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.