This is the third article in a four-part investigative series on the Chicago Police Department and the Independent Police Review Authority. Also see Part I, Part II, and a recent update.

It was 12:45 am when Dorothy Holmes’ phone rang, on October 12, 2014.

As thousands of athletes across the city slept in preparation for the Chicago marathon, commencing the next morning, a family friend told Holmes that her son Ronald “Ronnieman” Johnson had been shot by police, 10 minutes prior. Holmes raced to the hospital, but never saw her 25-year-old son alive again.

Hours later, on the southernmost stretch of the marathon route, at Chicago Police headquarters, approximately 45,000 runners would pass within two-and-half miles of where the killing took place, off of King Drive. Another 1.5 million people cheered along the marathon participants.

Like many police shooting deaths, Johnson’s story initially flew beneath the radar.

But like those that took place or emerged in the same month, the shooting death of Johnson, alongside those of Pedro Rios. Jr and Laquan McDonald, has reemerged, rocking the foundation of Chicago’s police accountability system, as the city prepares to pay reparations to survivors of police torture, in a historic win by activists.

Seventeen-year-old Tykwon Davis has been held at Cook County Juvenile Detention Center for the last two months, charged with assaulting a police officer, after being shot 11 times in front of witnesses.

At the beginning of October of 2014, the Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA) posted an “officer-involved shootings” report, bearing the City of Chicago seal and a grave error. Attributed to the time and place where 14-year-old Pedro Rios Jr. was shot in the back by a police officer and lived his last moments, a mark records “non fatal.” Like the killing of Laquan McDonald – a 17-year-old who was shot 16 times, one week after Johnson – the shooting of Rios was captured on video, currently suppressed by authorities.

By the end of the same month, when IPRA’s chief administrator, Scott Ando, testified at the annual City Council budget hearings, a different trio of males survived their wounds from bullets fired by police in the same time span.

Among them is 17-year-old Tykwon Davis, who has been held at Cook County Juvenile Detention Center for the last two months, charged with assaulting a police officer, after being shot a total of 11 times according to his mother, Willette Middleton. Witnesses dispute the police claim that Davis pointed a gun.

“He’s suffering real bad,” Middleton told Truthout. “He can’t walk. He lost a lot of weight. He was improving. But now that he’s incarcerated, he’s deteriorating. His bones are getting stiffer, the doctor said.”

Willette Middleton and son Tykwon Davis, recovering in the hospital after being shot by police in October, 2014. (Courtesy of Willette Middleton)

Willette Middleton and son Tykwon Davis, recovering in the hospital after being shot by police in October, 2014. (Courtesy of Willette Middleton)

“I tried to get them to give me some time to let him get well. He got halfway well. And the state came and got him and locked him up, and he’s been locked up ever since.”

The day before Davis was shot, the chief administrator of the public body tasked with police oversight, delivered his testimony to a City Council chamber in which fewer than a dozen of 50 members were reportedly present.

Ando did not use his platform to intervene, ring the alarm, or so much as address the month of horror undergone by shooting victims and their families – civilians among the many taxpayers footing the bill for IPRA, Chicago Police, and City Hall itself.

“IPRA is considered to be the gold standard of oversight agencies,” said Ando, whose previous law enforcement career spans three decades.

Yet the true standard of Chicago Police oversight, lived out in the streets and civilian lives, is that of police impunity, underwritten by the rote justification of shooting deaths; the purging of misconduct allegations; intimidation of complainants; and officer penalties rarely representing more than a slap on the wrist.

For those subjected to fatal and nonfatal forms of police misconduct alike, the complaint system – set in place by City of Chicago code, Illinois law and Chicago police directives – is one bearing the hallmark of retraumatization rather than redress.

“It was hard to talk to IPRA and still not get answers,” Dorothy Holmes told Truthout. “I told them my son was murdered, and they said, ‘Well, that’s not what homicide means.’ I said, ‘Yes it is. Look it up. I got a dictionary and I looked it up. You show me a dictionary with another definition.'”

“We all know they working with the police,” she said. “It was a waste of time. They said that [Cook County State’s Attorney] Anita Alvarez has the folder now, so they haven’t questioned the officer yet. All they told me is, ‘We can’t release information.'”

Middleton is certain she has received no contact whatsoever from IPRA, as she lost her job after the shooting, staying home to take care of her son. “Ain’t nobody came, and nobody called me. Ain’t nobody.”

Meanwhile, the dizzying pace of ongoing violence makes the incidents themselves, let alone their outcomes, difficult to track.

“For every Trayvon Martin that you’ve heard of, there’s 20 Craig Halls that you never do,” said La Toya Boose.

Suburban police shot and killed her cousin, Craig Hall, a Chicago resident, five days after the death of Laquan McDonald.

“There needs to be consequences for police violence,” Matthew Clark told Truthout.

Five years ago, after an extensive beating by police, alongside a friend, captured on video, Clark filed a misconduct complaint that remains open with IPRA, whom he describes as, “antagonistic from Day 1.”

“People need to know the structural support of police violence that exists in our city. It’s a machine … and IPRA is a part of the machine,” said Clark.

Investigating Misconduct Investigations

In the following report, documents disclosed to Truthout by Clark reveal patterns of IPRA’s institutionalized police bias – likewise observed by Truthout among the agency’s “justified” shooting investigations, assessed in depth at the report’s conclusion. Along the way, Truthout sought to unravel the fate of the vast majority of civilian misconduct complaints, which the investigation revealed are effectively purged.

The true standard of Chicago Police oversight is that of police impunity, underwritten by the rote justification of shooting deaths.

Three years of media accounts and closed investigations were studied, alongside public statements and reports generated by four separate city agencies involved in the accountability process, across three years. Instances of complainant intimidation, involving sexual assault, eavesdropping law, and the experience of three Chicago Police officers themselves, are included in the investigation, informed by analysis of related state laws and Department of Justice best practices.

In January of 2015, Truthout interviewed IPRA’s spokesperson, Larry Merritt, who has not responded to multiple, detailed, requests for follow-up, or granted Truthout’s request to interview Chief Administrator Ando, since. The office of Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez, asked multiple times for comment on the cases of Ronald Johnson and Tykwon Davis, and the nature and outcome of at least 190 cases referred to the office by IPRA since January, 2012, did not respond either. The mayor’s office has been contacted a second time, asked to comment by the final installment of Truthout’s series on its monitoring of the accountability system.

Two civil rights lawyers, two IPRA interns, a spokesperson for the office of Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan, and Clark’s fellow complainant, also interviewed or corresponded with Truthout throughout the course of the investigation.

From OPS to IPRA

In Independent Police Review Authority literature, a passage motivating the participation of IPRA investigators in Chicago Police Training Academy, surmises the agency’s view of its mission. “IPRA investigations enforce CPD standards as set forth in CPD policy,” according to its most recent annual report.

Hailed as an independent, civilian replacement of the Office of Professional Standards inside the Police Department, IPRA was founded on public sentiment and political promises.

The vast majority of police misconduct allegations received by IPRA are referred directly back to Chicago police.

Amid mounting outcry over the mishandling of police misconduct, the accountability agency was created in 2007. At the time, a video showing an officer viciously beating his bartender served as the final straw scandal. Gone viral at the onset of the YouTube era, it depicted a brutal, extended attack on the type of victim the mainstream would not ignore: a diminutive, young white woman, Karolina Obrycka.

Aside from simply documenting the brutality, the larger story in its aftermath was one of cover-up. Officers in various roles, and among the highest ranks, were implicated in an attempt to conceal the young woman’s assault from the public. In 2012, a federal jury named Chicago Police, as a whole, guilty, in her related civil suit.

Now, the vast majority of police misconduct allegations received by IPRA are referred directly back to Chicago Police, Truthout found.

As a symptom of how little has changed, a 2014 video showed vice squad officers hitting an Asian-American female salon manager, Jianqing Klyzek, and threatening her with death and deportation. After authorities held the video in private for months, Klyzek’s civil suit put the footage on evening news. Chicago Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy placed one of the officers involved on desk duty, afterward. Acknowledging the history of Chicago police violence, McCarthy described “sensitivity” training taking place within the force and then asserted, “Everybody has bad days.”

Reflecting on IPRA’s creation, civil rights lawyer Locke Bowman remembered, “There was going to be a new kind of approach, informed by openness and honesty.”

“What has emerged is a situation in which one ineffectual agency was replaced by another ineffectual agency, independent in name only, with a long track record of ignoring and walking away from very serious allegations of police misconduct,” Bowman, executive director of the MacArthur Justice Center and clinical professor of law at Northwestern University, told Truthout.

Unsustained, Unfounded, Exonerated, Sustained

But in the view of spokesperson Larry Merritt, “The department is definitely independent,” and has made improvements in the average time needed to close cases; opened a new community satellite office; and achieved a “46 percent rate of positive findings.” [ii]

Questioned further, Merritt explained “positive findings” as representative of investigations reaching any definitive outcome at all. Two of three possible findings consider the officer not guilty: “exonerated” from their charge or being the subject of an “unfounded” complaint. Cases in which an officer is found guilty of the misconduct alleged are “sustained.”

Comprising the majority of IPRA cases, are those categorized as “unsustained” – deemed impossible to substantiate.

“People look at the Sustain rate as a barometer of success,” Merritt said. “It’s a variable, but what’s most important is that the right conclusion is reached, the correct outcome is reached. If there’s a 100 percent sustain rate, no one would believe that 100 percent of the time police acted out of policy.”

Yet nearly 100 percent of the time, officers avoid discharge from the department, with a tiny fraction of cases proceeding through the full system of accountability, to close at the Police Board. Appointed by the mayor, its nine members rule on all cases involving an officer’s potential firing, as well as requests to decrease the length of suspensions.

“It takes a lot of work to really get one of those sustained investigation results,” explained former IPRA intern Kenneth Robinson, who assisted with intake and summarized audio and video evidence for six months.

“Everything has to be on point. If there’s video evidence, it has to be clear. There’s a lot of very bad footage. There has to be an OEMC [Office of Emergency Management and Communications] call to match. Everything needs to be linked. I only saw a few. Most of them generally were unfounded.”

A Cross-Section of Accountability

Between 2012 and 2013, as the Independent Police Review Authority logged nearly 16,000 allegations and weapon discharge notifications, the Police Board reviewed 77 separation decisions, discharging 21 officers and suspending 26.

The Board considered 17 charges as withdrawn, “due to the resignation or death of the respondent,” and also reduced the penalties of 10 officers.

In the same years, the City of Chicago Department of Law requested payment of more than $132.2 million to settle lawsuits naming Chicago Police.

Meanwhile, on streets far from City Hall, police officers shot and killed 25 civilians. Among them were 11 youths between the ages of 15 and 24.

As uncovered by Truthout, IPRA reported the fatal shooting of only 21 civilians to the public in 2012-2013, and in 2014 categorized the fatal shooting of Pedro Rios, Jr. as “non fatal” – pulling data directly from Chicago Police.

Mixed Messages: Mediation and Tasing

Former Drug Enforcement Administration agent Scott Ando was appointed and promoted to lead the Independent Police Review Authority by Mayor Emanuel in early 2014.

Ando promoted the expansion of the agency’s mediation program, offering reduced penalties to officers named in “investigations likely to be sustained,” which thereby “reduces the amount of time an officer is kept off the streets.”

While testifying at budget hearings, Ando focused on purported gains made by IPRA under his leadership. But he also attempted a corrective, stating, “[M]any academics, police accountability organizations, the media and others … often cite IPRA as having a Sustained rate of just 1 to 3 percent. This analysis erroneously includes Notifications (i.e. Taser discharges with no allegation of misconduct).”

Yet it is unclear why weapon discharge notifications, including Tasers, would not be counted among investigations performed by IPRA. Ando’s own explanation of the agency’s tasks, during the same statement, includes multiple references to the investigation of tasings.

But moreover, Taser use by Chicago Police has been deadly. Two weeks later, activist testimony on the police tasing death of 23-year-old Dominique Franklin Jr. became international news, riveting the United Nations Committee Against Torture.

But back at City Hall, Ando promoted the expansion of the agency’s mediation program, offering reduced penalties to officers named in “investigations likely to be sustained,” which thereby “reduces the amount of time an officer is off the streets.”

Sexually assaulted by a police officer, Moore was delayed by Internal Affairs and then intimidated from filing her complaint.

While the program may indeed save hours of negotiation with the police union, mediation does not signal improved public safety, but rather, improved impunity, in Truthout’s analysis of all 2014 case findings. Functioning as a mutually beneficial release valve, mediation allows more serious charges to be dropped, while guilt is admitted on minor procedural items, resulting in a slap on the wrist for the officer and an increased rate at which complaints are sustained.

Mass Referrals

Regarding the processing of complaints in general, in his City Council testimony, Chief Administrator Scott Ando acknowledged the limits of the Independent Police Review Authority’s jurisdiction, as set by city code, reverting certain categories of misconduct complaints directly back to Chicago Police.

What remained unsaid, however, is that it is the vast majority, of all complaints received that fall into Bureau of Internal Affairs’ categories.

City code mandates IPRA’s direct investigation of cases involving domestic violence; excessive force; coercion; verbal abuse; the discharge of a firearm, stun gun, or Taser; death or injury in police custody or lock-up facility; and those settled by the City of Chicago Department of Law.

Seemingly comprehensive, the parameters do not include matters of urgent, national concern regarding reforms in policing, such as stop-and-frisk; sexual assault; false arrest; and the denial of medical aid.

“There’s No Telling How Many Women He’s Done This To”

One case in particular, that of Tiawanda Moore, offers insight into the Internal Affairs culture where the vast majority of complaints are referred. With a fourth attempt at justice, as a civil suit enters court this summer, Moore herself serves as a leading example of the resolve demanded of civilians seeking to file reports of misconduct they believe must be made. Sexually assaulted by a police officer, the 21-year-old went to great lengths to file a complaint. She was delayed by Internal Affairs and then intimidated while filing her complaint; recording the interaction, Moore was thrown in jail for two weeks, after which she resubmitted her complaint and was found not guilty in her criminal trial.

Officer Jason Wilson, named in Moore’s civil suit, as the officer who assaulted her, appears in city data as a field training officer. The Internal Affairs investigators, Lieut. Richard Plotke and Officer Luis Alejo, who were recorded while pressuring Moore not to file, are listed among current city employees as well. Plotke has been promoted since the encounter.

“I wanted him to be at least fired from his job. I wanted – I wanted justice. I wanted someone to protect me,” Moore said on the stand.

“A Remedy in Search of a Problem”

The big picture of referrals, in cold hard numbers: Over the last three years, nearly 16,000 complaints, equivalent to 72 percent of the Independent Police Review Authority’s intake, have been referred to the Chicago Police Department’s Bureau of Internal Affairs, Truthout found. Among IPRA referrals in 2012-2013 [i], Internal Affairs investigated 22 percent – citing the remainder as “administratively closed.”

On average, five misconduct complaints are closed without investigation, per day, by the Chicago police.

In response to Truthout’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for two different months’ samples of “administratively closed” misconduct complaints, the request was denied as unduly burdensome. But the response was not without insight, explaining that more than 300 cases in the months requested were “administratively closed” – and therefore uninvestigated.

Across 2 full months, the metric provides a snapshot: On average, five misconduct complaints are closed without investigation, per day, by the Chicago Police.

For its part, IPRA’s denial of Truthout’s FOIA request maintains that the agency has no documentation whatsoever of the referrals, once made.

Yet the purging of complaints does not end there.

While oversight agencies in major cities such as Seattle and Los Angeles investigate anonymous and unsworn misconduct allegations, the Chicago Independent Police Review Authority does not – setting aside another two-thirds of complaints it retained in the years studied.

Illinois law and Chicago Police directives provide the basis for throwing out anonymous and unsworn allegations: a basis that does not conform to best practices followed elsewhere across the country.

“The Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies, CALEA Accreditation Standard No. 52.1.1 states that a written directive must require that ‘all complaints against the agency or its employees be investigated, including anonymous complaints,’ ” explains a Department of Justice publication on Internal Affairs guidelines.

According to CALEA’s website, 44 large, municipal police departments across the country are accredited and the Chicago Police Department is listed as undergoing the first stage of the process, “self-assessment.” Acquired by FOIA, the timing of the Chicago Police agreement with CALEA has the agency up for formal assessment in 12-18 months.

“At no time should a department seek to discourage a person from making a complaint because the investigation process is embarrassing or difficult.”

Put simply, the law is at odds with law enforcement policy experts. In a best practices guide, cited by the Department of Justice, the International Association of Chiefs of Police asserts, “Some departments feel that the credibility of the complainant should be assured by requiring a sworn statement from those who make the complaint. At no time should a department seek to discourage a person from making a complaint because the investigation process is embarrassing or difficult.”

Precedent also exists for alternate state law. “Under no circumstances shall it be necessary for a citizen to make a sworn statement to initiate the internal affairs process,” asserts the state of New Jersey’s Office of the Attorney General. Further south, in Kentucky, state law allows for investigations in the absence of sworn statements when allegations are otherwise substantiated.

Discussing the requirement with Truthout, Chicago civil rights lawyer Locke Bowman reasoned, “I’m sure it’s the case some of the complaints made are unwarranted. But getting to the bottom of that kind of situation shouldn’t be difficult or time consuming. It’s a remedy in search of a problem.”

***

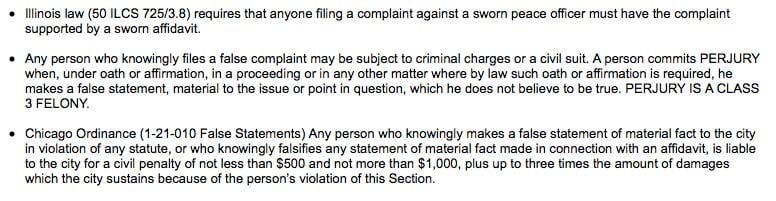

Screenshot of the Chicago Police complaint portal. In a letter concluding findings of a 2011 investigation, the Department of Justice described, “bolded and repeated admonitions regarding criminal liability for making false statements to police officers” as “a well-known deterrent to filing a complaint.”

Screenshot of the Chicago Police complaint portal. In a letter concluding findings of a 2011 investigation, the Department of Justice described, “bolded and repeated admonitions regarding criminal liability for making false statements to police officers” as “a well-known deterrent to filing a complaint.”

****

Moreover, the Chicago Police Department Member Bill of Rights directive, dictating the purging of anonymous complaints not criminal in nature, reveals stark disparities between rights granted accused officers and civilians, while dispensing marching orders to IPRA:

[P]rior to interrogation … the member will be informed in writing of the nature of the complaint and the names of all complainants … the member shall be provided with a copy of the portion of any official report that purportedly summarized their prior statement … the shooting member(s) will be required to give their statement … no earlier than 24 hours after the shooting incident … when a shooting member advances a claim that they are unable to provide a statement within the time period specified … IPRA will handle these claims … accepting at face value all good faith claims of a member’s inability to provide a statement.

Prioritizing civilian’s rights on the other hand, the sworn statement requirement is rendered detrimental and unnecessary in the context of civil rights litigation, explained Bowman.

“The process encapsulates IPRA’s entire approach … consistently devoting energy to obstructing victims.”

“In every case in which a civil rights complaint against an officer is serious and substantiated to the point where a lawyer has vetted the allegation, investigated the situation and concluded a lawsuit be filed, the complainant is already going to be giving a deposition under oath about what happened,” he said.

“Meanwhile, lawyers representing the officer charged with misconduct will look to use any prior statement to impeach and discredit the plaintiff by citing what is or isn’t in the statement and how it may or may not be consistent with other circumstances. An affidavit has a very real downside.”

“Anybody Could Experience This … and Nothing Would Happen”

At his home, pausing occasionally to help his wife care for the couple’s newborn son, Matthew Clark spoke with Truthout on the police beating he endured with Matt Clark’s co-plaintiff, and his dealings with the Independent Police Review Authority in the years since. Most recently, Clark has spent hundreds of hours attempting to obtain documents related to his own case.

Matthew Clark following his 2010 beating by Chicago Police officer. An involved officer remembered Clark’s eye color but did not recall seeing any visible injuries on his face. Clark and his fellow complainant’s complaint remains open with the Independent Police Review Authority. (Courtesy of Matthew Clark)As the result of protracted negotiations between an IPRA attorney and an assistant attorney general with the Illinois Public Access Bureau – who intervened as a result of an appeal filed by Clark after IPRA denied his initial Freedom of Information Act request – the battle over the records did not come as a surprise to Clark.

Matthew Clark following his 2010 beating by Chicago Police officer. An involved officer remembered Clark’s eye color but did not recall seeing any visible injuries on his face. Clark and his fellow complainant’s complaint remains open with the Independent Police Review Authority. (Courtesy of Matthew Clark)As the result of protracted negotiations between an IPRA attorney and an assistant attorney general with the Illinois Public Access Bureau – who intervened as a result of an appeal filed by Clark after IPRA denied his initial Freedom of Information Act request – the battle over the records did not come as a surprise to Clark.

“The process encapsulates IPRA’s entire approach … consistently devoting energy to obstructing victims,” said Clark.

It is important to note, as Clark and his fellow complainant do themselves, their case is not typical of alleged police misconduct in Chicago.

Said Clark, “We’re two white guys … What happened to us happens to minorities in this city, and this country, everyday, without justice. There is no justice for anyone.

“If you’re someone who thinks it couldn’t happen to you, don’t fool yourself. The system has fully established itself on the backs of minorities for years. If you’re in the wrong place at the wrong time, it will chew you up and spit you out, without a doubt.”

“They operate with this kind of resentment towards the victims. As if they had been wronged … as if your request for justice wronged them.”

Considering his initial call to IPRA “naïve,” Clark remembered, “Justice then was literal and personal to the situation I was in. I wanted the individuals who beat us to be held responsible, along with the police officers who allowed it to continue. I could not believe such a thing should transpire without consequence.

“But the investigatory and legal system is stacked against you. It’ll never happen.”

Upon returning home from the hospital with a concussion, Clark called 911 and was transferred to IPRA. He and Gramsci described a series of events from there, which have led Clark to believe, “Justice now is exposing why nothing would happen.”

Among their experiences: the IPRA investigator who answered the initial call, in which the complainants describe being told multiple times to “think twice before filing,” was assigned to their case; the reinterpretation of one of their own statements, cast in less favorable light and an adversarial posture and the involvement of uniformed officers, in their complaint proceedings, as constants.

“They operate with this kind of resentment. As if they had been wronged … as if your request for justice wronged them. It’s the victim on trial with IPRA,” said Clark.

Justified

Of the 25 fatal shootings which occurred between 2012-2013, 10 hadIndependent Police Review Authority investigations closed as of Truthout’s deadline. Each closed as justified. Two of the killings involve civilian witnesses who appear to have substantiated officer allegations of a deadly threat posed to other civilians by the victim.

The majority of cases, however, involved highly questionable shootings: of victims unarmed and/or shot in the back and an aftermath of accounts in dispute between police and civilian eyewitnesses. Yet rather than exhibit a high level of scrutiny, corresponding IPRA investigations include aberrations in evidence and interpretation of events in line with police.

Here, Truthout studies five “justified” shooting cases. [iii]

Fatal shooting investigations, sustained case summaries, and reports and data of the Police Board, the Independent Police Review Authority, and Internal Affairs. For full complaint data studied, visit IPRA’s quarterly reports at www.iprachicago.org/resources.

Antowyn Johnson

A 24-year-old, Black man, Johnson emerged from a van being followed by police and ran, as officers in a squad car pursued him. The dash-cam was “not functional that day,” IPRA’s investigation notes, citing a repair order made by police.

Johnson fell, the police account acknowledges. The officers interviewed by IPRA assert that he was shot in the back, face down on the ground, as a result of pointing a weapon at the squad car, while prone.

IPRA’s 12-month investigation begins with a summary, later described as containing facts. The summary includes no mention of attempts to view surveillance video along the six blocks of the incident route, where the van in which Johnson was a passenger moved “erratically,” according to police, prompting the encounter. The vehicle passed a Police Observation Device (POD), recorded by Google Maps both before and after the shooting. A public school sits along the same route, of relevance considering the 4,500 Chicago Public Schools cameras linked to the city’s Office of Emergency Management and Communication system. IPRA’s investigation makes no mention of attempts to research or obtain footage from either video recording system.

At the shooting site, a POD a half block away from the shooting “did not capture any images of evidentiary value,” IPRA’s investigation notes. Chicago Police literature describes the devices as “equipped with night vision capability” able to “operate 24 hours a day in all weather conditions … equipped with technology to detect gunfire.”

Johnson’s alleged weapon was found “several feet away” from his body – without fingerprints and without a magazine clip.

Among additional aberrations in the investigation: A discrepancy made by one of the involved officers in identifying his weapon; an update to one of the involved officer’s statement weeks later; the absence of an interview with the officer reported as having found the magazine of bullets matching Johnson’s alleged gun, one block away; the description of a “large injury” to Johnson’s hand as a “graze wound.”

Derrick Suttle

A 47-year-old unarmed Black man, Suttle was shot multiple times by an off-duty officer in uniform. After confronting Suttle in the alley behind his house, where Suttle was driving a van, the officer shot him. Later, he cited fear for his life after Suttle maneuvered his vehicle, causing the officer to fall.

IPRA’s investigation mentions no residual evidence of weapon discharge on Young’s hands in the autopsy report.

IPRA’s 19-month investigation mentions no attempts made by the agency to interview witnesses beyond the shooting officer’s spouse and a blind man present. Nor is there mention of contacting neighbors, one of whom called 911 the night of the shooting to relate an account in which the officer is described as yelling at Suttle and then shooting him – with no mention of apparent danger. More than eight hours past the incident, the officer was administered the mandatory Breathalyzer test. According to IPRA’s investigation, the lag in time involved transport to the hospital and treatment for the officer’s bruised leg and a “small laceration” on one hand.

Divonte Young

A 20-year-old Black man, Young was shot in the back by undercover narcotics officer and found dead, face down in an alley, by paramedics. Having allegedly fired at other civilians and pointed a gun at the officer, according to the police account, Young’s weapon was not recovered. A current civil suit complaint alternately describes Young as unarmed and in need of unadministered medical aid.

“How would she feel if it was one of her kids killed by the police?”

IPRA’s 18-month investigation includes a Preliminary Summary Report, written the day of the shooting, which does not state Young pointed a weapon at the officer prior to the officer’s shooting. The investigation goes on to also cite a statement given by the officer later, which claims Young fired on nearby civilians and pointed a gun at him twice. IPRA’s investigation mentions no residual evidence of weapon discharge on Young’s hands in the autopsy report. As proof of Young’s assault, IPRA cites police departmental reports, which “show that Officer A was assaulted by Subject 1,” but the investigation also notes that no video of any kind could be obtained of the incident.

Tywon Jones

A 16-year-old, Black child, Jones was engaged in a shooting with neighborhood rivals, according to eyewitness. Police officers in an unmarked car then pulled up behind the teen, and one officer shot him five times in the back. One eyewitness told media on the scene, “He was still in the car and shot him and got out the car and stood over him and shot him again … Yeah, I was sitting right here.” IPRA’s investigation reports negative results in finding eyewitnesses to the police shooting however, including civilians who did not see it take place. The involved officers mention using their horn, but do not claim to have ever announced their office before firing at Jones, who they claimed shot at the officers, while riding his bike in the opposite direction. No mention is made of attempts to gather Police Observation Device footage or other video.

Jamaal Moore

A 23-year-old, unarmed, Black man, Moore was shot twice in the back at close range while attempting to flee. The killing was captured on video, which “clearly depicts images of the incident as described in Chicago Police Reports,” according to IPRA’s investigator who closed the case after 11 months; and both a district judge and a City of Chicago lawyer highlighted contradictions between the police account and the video, while presiding over a $1.25 million civil suit settlement granted Moore’s family.

“Whoever I Got to Go to… I’m Gonna Do It”

Ronald “Ronnieman” Johnson was a 25-year-old father, and the eldest son of Dorothy Holmes, who has filed a civil suit against the City of Chicago. (Courtesy of Dorothy Holmes)Dorothy Holmes, the mother of Ronald Johnson, has a question for Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez, whose office is deliberating whether or not criminal charges will be brought against the officer who shot her son – while prosecuting 17-year-old Tykwon Davis, who was shot in the back by police, for assault of a police officer.

Ronald “Ronnieman” Johnson was a 25-year-old father, and the eldest son of Dorothy Holmes, who has filed a civil suit against the City of Chicago. (Courtesy of Dorothy Holmes)Dorothy Holmes, the mother of Ronald Johnson, has a question for Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez, whose office is deliberating whether or not criminal charges will be brought against the officer who shot her son – while prosecuting 17-year-old Tykwon Davis, who was shot in the back by police, for assault of a police officer.

“How would she feel if it was one of her kids killed by the police?” Holmes said.

But Holmes is not banking on action from Alvarez. “If I gotta go to the Feds, FBI, or whoever I got to go to, to get the officer brung up on charges, I’m gonna do it.”

“They murdered my son. They can’t kill somebody else and get away with it.”

In the concluding installment of the series, Truthout will track trends in the Chicago Police Department under the leadership of Superintendent Garry McCarthy and explore avenues for reform, including precedent surrounding a Department of Justice Civil Rights Division pattern and practice investigation.

NOTES:

i. Internal Affairs has not released 2014 data, as of Truthout’s deadline.

ii. As of late January, 2015 when Merritt stopped responding to Truthout’s request for comment.

iii. IPRA’s investigation into the shooting death of 17-year-old Christian Green was covered previously by Truthout. The remaining two shootings occurring under the current administration with cases closed, studied by Truthout, will be covered in a forthcoming series installment.

We’re not backing down in the face of Trump’s threats.

As Donald Trump is inaugurated a second time, independent media organizations are faced with urgent mandates: Tell the truth more loudly than ever before. Do that work even as our standard modes of distribution (such as social media platforms) are being manipulated and curtailed by forces of fascist repression and ruthless capitalism. Do that work even as journalism and journalists face targeted attacks, including from the government itself. And do that work in community, never forgetting that we’re not shouting into a faceless void – we’re reaching out to real people amid a life-threatening political climate.

Our task is formidable, and it requires us to ground ourselves in our principles, remind ourselves of our utility, dig in and commit.

As a dizzying number of corporate news organizations – either through need or greed – rush to implement new ways to further monetize their content, and others acquiesce to Trump’s wishes, now is a time for movement media-makers to double down on community-first models.

At Truthout, we are reaffirming our commitments on this front: We won’t run ads or have a paywall because we believe that everyone should have access to information, and that access should exist without barriers and free of distractions from craven corporate interests. We recognize the implications for democracy when information-seekers click a link only to find the article trapped behind a paywall or buried on a page with dozens of invasive ads. The laws of capitalism dictate an unending increase in monetization, and much of the media simply follows those laws. Truthout and many of our peers are dedicating ourselves to following other paths – a commitment which feels vital in a moment when corporations are evermore overtly embedded in government.

Over 80 percent of Truthout‘s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and the remaining 20 percent comes from a handful of social justice-oriented foundations. Over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors, many of whom give because they want to help us keep Truthout barrier-free for everyone.

You can help by giving today. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger gift, Truthout only works with your support.