Jared Rodriguez / Truthout)” width=”308″ height=”349″ />Kochs. (Image: Jared Rodriguez / Truthout)Peter Buffett, the second son of billionaire investor Warren Buffett, worries that the state of philanthropy in America “just keeps the existing structure of inequality in place.” At meetings of charitable foundations, he says “you witness heads of state meeting with investment managers and corporate leaders. All are searching for answers with their right hand to problems that others in the room have created with their left.”

Jared Rodriguez / Truthout)” width=”308″ height=”349″ />Kochs. (Image: Jared Rodriguez / Truthout)Peter Buffett, the second son of billionaire investor Warren Buffett, worries that the state of philanthropy in America “just keeps the existing structure of inequality in place.” At meetings of charitable foundations, he says “you witness heads of state meeting with investment managers and corporate leaders. All are searching for answers with their right hand to problems that others in the room have created with their left.”

Describing the stunning growth of what he calls a “charitable-industrial complex,” his recent New York Times op-ed reads in confessional style: “People (including me) who had very little knowledge of a particular place would think that they could solve a local problem.”

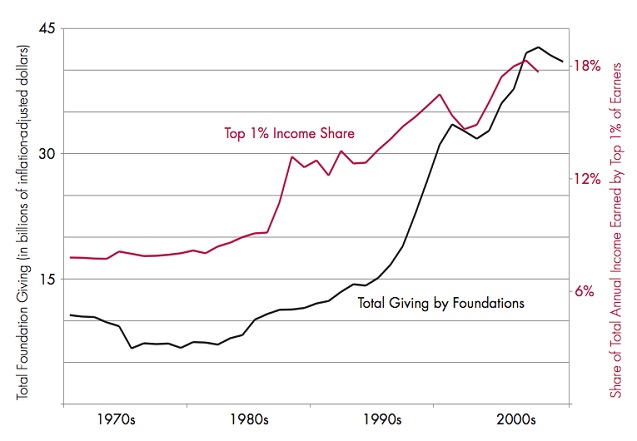

An insider’s critique from someone like Peter Buffett is certainly welcome. Charitable giving, after all, has seen a meteoric rise in recent years, virtually unchanged amid a historic global recession. In what the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy calls a “New Gilded Age of Philanthropy,” the ballooning fortunes of the 1% seem to mirror levels of giving by foundations:

(Source: National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy)

(Source: National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy)

As Buffett suggests, this growth in elite largesse, totaling $316 billion in 2012, has done little to combat economic inequality. But the problem isn’t just one of ineffectiveness. A recent paper published in the Journal of Economic Inequality shows philanthropy hasn’t simply failed to meet its goals; it’s made the situation worse.

“Using measures of both absolute and relative inequality,” the study’s authors conclude, “we have shown that philanthropy may actually exacerbate inequality, instead of reducing it.”

It’s hard to believe that all the industrial titans and Wall Street tycoons shelling out billions on charitable projects don’t understand this. They spend their lives swimming in numbers. What, then, might their real goals be? A closer look at how the world’s wealthiest are choosing to give away their money provides clues. While pretending to fix inequality, contemporary philanthropy’s actual role has been to strengthen the arrangements that make gross inequality possible in the first place. It has become a weapon in the class warfare of the 1%, the carrot to win people over to their ideology complementing the stick of political spending to coerce them into the same.

The Koch brothers

David and Charles Koch, together worth $35 billion, have perfected this philanthropic misanthropy perhaps better than anyone else. Their Kansas-based Koch Industries is the second largest private company in the country after Cargill, with annual revenues estimated to surpass $100 billion. Together they control thousands of miles of oil pipelines from Alaska to Texas; fertilizers, minerals and biofuels; Brawny paper towels, Dixie cups and Lycra.

A research team at American University found that from 2007 to 2011, Koch foundations gave $41.2 million to 89 nonprofits and sponsored an annual libertarian conference. The report details how Koch Industries’ $53.9 million federal and state lobbying budget routinely goes hand-in-glove with Koch-affiliated nonprofits’ “public advocacy” for reasons having little to do with the public and everything to do with the brothers’ sprawling business interests. Koch lobbyists advocate for bills like the Energy Tax Prevention Act — which sought to roll back the Supreme Court ruling allowing EPA regulation of greenhouse gases — that are then supported in congressional testimony by “experts” from Koch-funded nonprofits.

Though private foundations cannot legally “be organized or operated for the benefit of private interests,” the study’s authors note that IRS enforcement is largely “sporadic and somewhat mysterious,” and even in the case of an investigation communications between the foundation and the government are generally kept from the public. The Koch nonprofit machine has exploited this loophole for all it’s worth, testifying before congressional committees at least 49 times since 2007.

For decades, Koch philanthropy has also waged ideological warfare within U.S. universities, contributing over $30 million to 221 universities since just 2011. Here, the payoff couldn’t be plainer. A 2012 report in Academe documented theKoch-funded coup in Florida State University’s economics department, showing how “in exchange for his ‘gift,’ the donor got to assign specific readings, select speakers brought to campus and instruct them with regard to the focus of their lectures, shape the curriculum with new courses and specify the number of students in the courses, name the program’s director, and initiate a student club.”

The Charles G. Koch Foundation gave FSU $1.5 million to sponsor two assistant professors, fund fellowships and shape curricula promoting free-enterprise doctrine. It then created an advisory board to distribute money to faculty and ensure their work aligned with the foundation’s ideology.

The Kochs have tapped many useful allies, academic and non, in their collegiate ploys. A year before the FSU story, Inside Higher Ed exposed how administrators at Clemson University cultivated the Koch Foundation to build its “Institute for the Study of Capitalism,” receiving $1 million for the effort. BB&T, the financial institution whose former chairman and CEO John Allison heads the Koch-backed Cato Institute, regularly pays universities to chair favorable professors, typically in economics. Cooperative institutions are rewarded with Koch dollars as a bonus. American University’s Investigative Reporting Workshop found 10 such universities, where BB&T-chaired professors coincided with Koch cashflow.

Art Pope

James “Art” Pope, a founding board member of the Kochs’ conservative advocacy group Americans for Prosperity, took the brothers’ brand of charitable devastation and concentrated it at the state level. He is, as the New Yorker’s Jane Meyer put it, the “conservative multimillionaire [who] has taken control in North Carolina,” a discount retail baron that has used his unrivaled influence as the state’s single largest political donor to literally buy his way into office. While his network of conservative foundations continues steering the debate rightward, Pope puts policies in motion as the state’s deputy budget director.

The Institute for Southern Studies has extensively documented how Pope uses his family nonprofit — the John William Pope Foundation, worth nearly $150 million — to pour tax-exempt donations into thinly veiled conservative advocacy groups like the John W. Pope Civitas Institute, the John Locke Foundation and the Pope Center for Higher Education Policy. Over the years, these groups have worked closely with Tea Party organizers, attacked climate science (andscientists) and generally championed free market principles.

Pope’s is an impressive empire of shell charities: his foundation spends more than two-thirds of its money providing some 90% of the funding for North Carolina’s leading conservative organizations, at most of which he enjoys a leadership role. In 2010, three of these groups — Civitas Action, Real Jobs NC and Americans for Prosperity — banded together with Pope and his family toflood North Carolina’s legislative races and stage the first Republican takeover of the state since 1896.

Since then, Pope’s puppeteering has pushed North Carolina into free-fall, galvanizing the grassroots, Moral Monday opposition that’s spreading across the country. Policies long advocated by Pope foundations are now proposed and enacted on a daily basis, seeking to eliminate corporate and income taxes,shrink healthcare coverage, gut environmental regulations, remove early education opportunities, oppose public transit and defund public schools andhigher education.

It’s this last foray that student groups like the North Carolina Student Power Union are fiercely resisting, mounting a statewide campaign against Art Pope’s involvement in the University of North Carolina system. In exchange for his foundation’s more than two dozen grants over the past 15 years, last year Popewas rewarded with a seat on UNC’s “blue ribbon” panel to craft a five-year strategic plan for the 16-campus system. Students claim the move defies UNC’s mandate for public accountability, reeking of blatant corruption.

Pope is hardly an educator, and his gifts demonstrate a Koch-like determination to indoctrinate college students at any cost, bidding to bring them into the fold while they’re young. His past contributions include $900,000 for pro-free market political science program at North Carolina State University; an attempted $10 million for a UNC program in “Western civilization,” later diverted to football coaches’ salaries after widespread outcry; and a similarly ill-fated $600,000 attempt to launch a constitutional law center led by the director of a Pope-funded nonprofit at North Carolina Central University.

Bill and Melinda Gates

But it’s not just rightwing demagogues who have “drank all the Tea Party they could drink and sniffed all the Koch they could sniff” using charity to further their political agenda. Bill and Melinda Gates’ own liberal-leaning, $36.4 billioncharitable foundation, by far the world’s largest, has long been scrutinized for attempting to fix with one hand the problems it creates with another. In 2007, the Los Angeles Times uncovered “hundreds of Gates Foundation investments — totaling at least $8.7 billion, or 41% of its assets… in companies that countered the foundation’s charitable goals or socially concerned philosophy.”

These included endowment holdings in top polluters like ConocoPhillips and Dow Chemical Co., oil refineries and paper mills that sicken the children whose parents the foundation treats for AIDS, and “pharmaceutical companies that price drugs beyond the reach of AIDS patients the foundation is trying to treat.”

The Gates Foundation’s dealings with lifesaving drugs in particular showcase the contradictions of today’s philanthrocapitalism.

Although leading global health campaigners want an end to Big Pharma’s monopoly drug patents to increase affordability in poorer countries, the Gates Foundation opposes any changes to existing intellectual property law. Advocates for loosening IP regulations point out that doing so would both lower prices by encouraging generic competition and enable innovation outside of patent-hoarding companies. This proposal, however, threatens multinational pharmaceutical corporations, well-represented among foundation leadership, as well as monopolistic firms like Microsoft, which as late as 2007 was lobbying the G8 to tighten global intellectual property protection — a move Oxfam has consistently warned spells disaster for the health crisis in the Global South.

The Timesreport traces the effects of this position on the ground, quoting an intellectual property expert who claims the foundation’s stance makes “medicines available only to a narrow spectrum of a rich elite in a developing country” in a form of “pharmaceutical apartheid.” As millions of impoverished AIDS and HIV patients are priced out of the market, lucrative patents allow the world’s top 10 drug companies to collect some $80 billion in profit annually. And Gates sure won’t stop them.

Boards of broken trust

The overtures by Art Pope and the Kochs show how the American university itself has lately emerged as a hub of misanthrope philanthropy, offering both opportunities for long-term indoctrination as well as short-term plunder. A 2010Chronicle of Higher Education study found that boards of trustees, many composed of top university donors tasked with making decisions that “profoundly affect everyone on the campus,” frequently conduct business with trustee-affiliated companies. According to the Chronicle, one in four boards at private colleges have such financial ties, signing contracts involving “banks, law firms, construction companies, and insurance conglomerates” linked to trustees. And the trend is accelerating, with 58% of colleges (64% among private institutions) now allowing business relationships with trustees, as opposed to 46% just two years ago.

These sorts of boardroom entanglements have led universities into profoundly embarrassing situations, like the fallout at Dartmouth after the 2008 financial crisis. As Todd Zywicki, a former Dartmouth trustee, later wrote, “The large contributions that were their ticket on to the board were functionally a mere downpayment for the fees that they would later receive for managing half a billion dollars of Dartmouth’s endowment,” 14% of which was at one point invested in trustee-affiliated hedge funds and private equity. By 2009, Dartmouth’s Wall Street-heavy board had packed 67.5% of its endowment into risky instruments, ending in a catastrophic crash that deepened the university’s debt and forced its credit downgrading.

Kenneth Langone, the $1.1 billion investor who founded Home Depot, recently made headlines for similarly capitalizing on his neatly purchased trustee appointment. His $200 million donation to NYU’s medical center, the largest in the institution’s history, earned him the renaming of the facility (it’s now theLangone Medical Center) along with what is now the Stern School of Business’s Langone Part-Time MBA. Also part of the deal was his appointment as vice co-chair of NYU and its medical center’s board of trustees, a position he abused in July to email staff about donating to the reelection campaigns of his favorite (very corporate-friendly) members of Congress. Coming as the “medical school clamps down increasingly on salaries and tenure,” employees reported feeling threatened and pressured to follow through.

More broadly, the Langone board at NYU has produced a string of harshly condemned decisions that in many ways encapsulate the world his brand of giving is working to create. It’s a closed circle of wealth, where money flows between toward massive expansion projects and million-dollar payouts for star staff’s condominiums while NYU students, among the nation’s most indebted, are left in the dust.

The change we need

For all its failures, today’s philanthropy continues to succeed as a form of self-therapy for the world’s rich. The philanthropic elite have won out in a not-so-pretty world of entrenched and widening inequality, and their charitable giving helps hide the ugly truth of the situation — from us as well as themselves. Ruinously for us, though, the ways in which our misanthrope philanthropists contribute are significantly deepening the crisis at hand.

Of course, there are occasional flickers of light that emerge from the nonprofit world. Foundations like Marian Wright Edelman’s Children’s Defense Fund, growing out of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign to advocate for working-class families, and the new International Organization for a Participatory Society, seeking to build a bottom-up, classless global society, work for the poor and powerless in important ways. Still, trapped in the logic of competing cashflows, these groups are overshadowed by their misanthropic counterparts.

To echo Peter Buffett’s call, what we need is “systemic change… built from the ground up.” No more scraps from the rich kids’ table. The idiosyncratic, undemocratic “giving back” of the world’s wealthiest in the end gives to nobody but themselves, some more brazenly than others. As philanthropy analyst Michael Edwards asks: “Would philanthrocapitalism have helped fund the civil rights movement in the US? I hope so, but it wasn’t ‘data driven,’ it didn’t operate through competition, it couldn’t generate much revenue, and it didn’t measure its impact in terms of the numbers of people who were served each day. Yet it changed the world forever.”

We’re all still waiting for the change we really need, not the kind dropped from swollen pockets.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.