“Tent City” is a place hidden out of sight and historically out of mind. It sprawls over a mud-rutted, brush-tangled acre of landscape nestled under a network of highway bridges along the Cumberland River on the outskirts of downtown Nashville, Tennessee. It is impossible to find unless one is directed or taken there. The camp is surrounded by a variety of chain-link fencing placed in different configurations that appear to have been installed in stages over many years.

This community of homeless men and women, constantly fluctuating in size, has been, to date, largely flying under the city’s municipal radar. It appears that the camp has provided an unspoken service for the city as an alternative to municipal shelters, historically catering to a population of homeless, fringe people who might be battling drug and alcohol addiction or suffering from untreated mental illness, or the occasional sex offender avoiding mainstream society.

Recently, there has been a change at Tent City; the population is growing at a staggering rate. One consequence is that more attention is being given to this group of nearly 100 residents and their makeshift dwellings by both the media and advocacy groups.

Wendell Segroves, the unofficial leader of the homeless community Tent City in Nashville, Tennessee, is like a father or chief leading his tribe.

Wendell Segroves, 52, who is the leader of the encampment, much like a father, says that the numbers are growing with the addition of new people who find themselves with no other place to live due to the harsh economy. Segroves lives in a small wooden dwelling in a back corner of the camp. He has three little, but tough looking, dogs, and has somehow managed both electricity and an Internet connection. He is wired into, and is on top of, the homeless scene both in Nashville and around the country. He contributes to homeless blogs and is working to build a network on the web to enable homeless people to engage and discuss issues.

Nashville Surge

Residents of Nashville’s Tent City collect fire wood from a load of scraps from a local construction site, dumped by a friendly driver.

The problem in Nashville now, Segroves said, is that the rapid growth of homelessness and poverty will soon overwhelm the Nashville social services’ ability to provide shelter and food. He explained that there are now about 13,000 homeless people in Nashville and 5,000 on the streets.

Segroves works with a feeding program for homeless and impoverished people, and, he said, “every time its new people” adding to the ranks using the program. “I don’t see it getting better any time soon,” he said.

There are over 30 homeless camps in the Nashville area according to Segroves; each may hold five to 20 people. The city government tries to find these encampments and remove them, he said, so the encampment dwellers keep quiet about where they live. The only reason that his Tent City has escaped city removal, he said, is because of media attention and the public support it has generated.

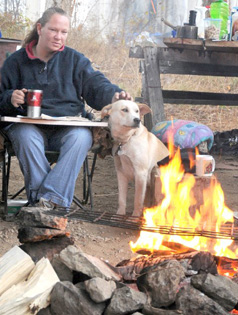

Cheryl Woodard works on a crossword puzzle. She suffers from seizures and keeps getting thrown out of the shelters because of the affliction.

A large dump truck pulls up to the front gate of the camp as we are talking. It’s loaded high with wood scraps from a local construction site. A voice from somewhere unseen and deep within the settlement barks out “All In … all in.” Slowly, bodies emerge from all corners of the camp moving at a pace consistent with the cold air and the heavy downpour of rain. The truck dumps the wood at the gate and slowly, without any discussion, the wood is carted off in different directions by the people of Tent City. Columns of white smoke drift out of many of the tents as people try to stay dry and warm. The donated wood is a benefit of the increased awareness of the camp as public opinion has softened toward the homeless in general.

As the Tent City residents move about the camp, the rain and mud intensify the environmental harshness facing them. Young and old, men and women, sit by their fires trying to stay comfortable.

J.T. (left) from Cleveland, Ohio, tends a fire outside a communal tent in Nashville’s Tent City. Tent City currently has about 70 homeless people living in tents and makeshift wooden structures.

Cheryl Woodard is working on a crossword puzzle and explains to me that she suffers from seizures and keeps getting thrown out of the shelters. She has lived in the camp for a month and a half. “They don’t understand me and keep accusing me of doing things like peeing in a bucket. After a seizure I’m really out of it for awhile.” Woodard is sitting in front of a huge, black plastic structure, which she says sleeps six people. To her left is a strong looking African-American man in his late thirties. He calls me a racist because I haven’t interviewed him yet. I tell him it’s the first time I’ve been called a racist, and he said he was kidding, but now we are talking. J.T. is from Cleveland, Ohio, and he declares loudly, that “there ain’t no work.” This is his forth time in Nashville as a homeless man.

There is a teenage boy sitting at the fire as well. He doesn’t move or say anything, just sits looking depressed and beaten. It’s the saddest moment of the day – youth in such despair. My teenagers at home often feel that momentary despair, but it is followed by a fight or an argument known to all parents of teenagers. Yet, our kids somehow find their way safely back to a place of balanced teenage joy. Not true for this young man. He sits and waits for something, anything, that just isn’t going to happen, and he knows it.

A teenage boy sits outside a communal structure in Tent City. The numbers of homeless teenagers is growing rapidly in the United States.

My next visit is to a tent made from wood and plastic. I look inside and find two men in tattered, filthy clothing. It’s like a scene from a movie showing the quintessential hobos of the Depression. They won’t talk to me or let me photograph them, so I move on.

There are dogs everywhere, tied to ropes or inside structures. One structure had a “No Trespassing” sign hanging on a chain across the entrance. Another makeshift hut was covered with an old billboard canvas with a huge image of a man smoking a cigar and looking very dapper. This was the icing on the surreal cake of Tent City.

Segroves said, “We just want to be left alone and get the services we need. Some guy was going to bring little huts down for us, but the city stopped it. I was going to make one of them a shower.”

There are dogs everywhere tied to ropes or locked inside structures at Tent City.

Segroves used to put wood chips on all the paths, but it was clearly a losing battle against the mud. I dropped him off at a local church where he could take a shower. On the way back, he picked up a 12-pack and some tobacco: “My little vice.”

Madge

My guide to Tent City and to understanding the homeless world of Nashville is Madge Johnson, who greeted me with a huge hug. She is a woman on a mission of compassion, and it’s clear that her empathy comes from a place of knowing harsh realities on a personal level. She is the perfect advocate for the homeless in Nashville, having been on the streets for over a decade herself.

“One cold night,” she said, “I found myself in a house with some older men.” Tears are streaming down her face at this point in the story, and she needs a moment to breath back to her voice. “It wasn’t about the sex, you know, tricking, or about the drugs or some beer. They were nice to me, and I had something to eat and I was warm. That’s when it hit me, I mean how low I had gone.” Hitting bottom, where only the very basics for survival like food and shelter were what mattered, this was the moment that shocked Johnson to her core and started her back in the direction of real recovery.

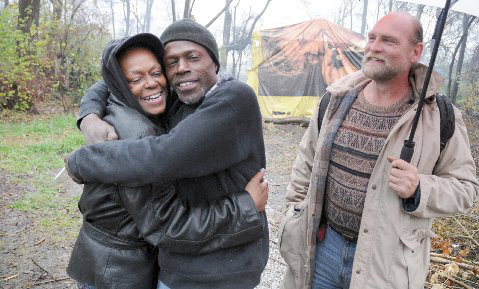

Madge Johnson (far right), outreach navigator for Nashville Homeless Power Project (NHPP).

Today she is clean and a pivotal staff member at Nashville Homeless Power Project (NHPP). Her co-worker and the executive director of the nonprofit organization, Jay Mazon, said, “There are no mistakes. Our experiences shape us to who we are. There is a reason for everything … this is why Madge is so good at what she does now. People can relate to her in a very real way and why she can ground the staff here”

The NHPP, with a small staff of paid workers and volunteers, is doing grassroots organizing to bring change in the municipal attitude and general public opinion about the issue of homelessness. Giving the homeless a voice and helping them find the services needed to get them back on their feet is the main objective. They have also set up an annual event that honors and remembers the homeless who have perished on the streets over the past year.

Homeless advocate Madge Johnson (left) gets a welcoming hug from a homeless man living in Tent City in Nashville as Wendell Segroves (right) looks on.

The organization is working with the courts and the Nashville Bar Association to help homeless people resolve legal problems instead of overwhelming the jails. Mazon explained, “It a program to help those unable to move forward because of their legal history. Those that are looking to sincerely improve their situation can have their records cleaned allowing them to get back to work and move forward.”

“We need money and I mean like yesterday,” Mazon said. “I was never homeless but I come from the working poor. I always wanted to give back.”

Sweeping Up in Memphis

Just a three-hour drive from Nashville, the cold winter is also impacting the homeless and the political fabric of Memphis.

A homeless man in Memphis, Tennessee, slowly and with great care folds plastic sheeting he uses to stay warm.

Memphis does not have a city-run, free shelter for men, and staying at the Memphis Union Mission shelter costs $6 a night after the first four nights free. There is also a fee for other privately-run shelters, and a picture ID is required. This is in a city where panhandling is a crime.

The Memphis police began enforcing a new policy on December 9, 2009, of rounding up and processing homeless people living on the streets. The plan initially was billed as a crackdown and sweep of the streets, but the police action soon mellowed into a community service action after Mayor A.C. Wharton Jr. was hammered by advocates for the homeless. You had nothing to worry about unless you were wanted on outstanding warrants, promised the chastened mayor.

“A Nudge”

It was not surprising, though, that on the first day of the new order, police found very few homeless milling around in their usual hangout locations. “If you stay out here they’re gonna take you to jail,” said Karl Nolan, who has been homeless in Memphis for the “last four months, this time.”

“I’m shining hubcaps trying to get enough money to pay for the shelter for a few nights,” said the theatrical Nolan. He relaxed after a few minutes of conversation and spoke of the growing numbers of homeless and how the city just doesn’t understand the problems faced by those on the street. I got a big hug as I left, and I gave him $20.

Karl Nolan, a homeless man living in Memphis, Tennessee.

An official gathering, documented by the press, around one of the few homeless people who had not vacated Memphis city center for a police sweep in December 2009.

Later in the morning, I found a gathering of police, media, city sanitation workers and a few homeless men in the city center. All the players clearly know their role in this scene. The police acting with civil restraint as members of the media watch at arms length, as if afraid to get too close. These few cornered homeless men, seen in their uniforms of layered dirty and tattered clothing, seem bewildered and confused at the attention.

Lt. Sandra Marshall of the Memphis Police Department explained that the homeless man who is the center of the group’s attention was found sleeping next to a trash can across from the Memphis Courthouse, but is “known” to be in that area most days. She said “he did not fit the criteria” mandated for the new city policy, which I found odd. She followed with, “I don’t think people should live like this in unsanitary conditions, and they need a nudge to find services.”

A homeless man in Memphis, Tennessee, who was moved along by police during a citywide sweep of the city center. The police said he is always there and so he “doesn’t fit the criteria” of the target group for the sweep.

“I’m tired and ashamed of who I am,” said Robert Warren, another street person sitting nearby, who was also caught in the sweep. He reads on from an unseen script, as from a play, about finding Jesus and wanting to finally change. He is surrounded by three, calm police officers, a social worker, a few photographers and one lone reporter.

The police on the scene were nonthreatening and working very hard to appear empathetic in their efforts to assist Warren, who has been homeless for ten years and is battling drug and alcohol addiction. Lt. Felix Calvi of the Memphis police department, who was standing stiffly by Warren, said they were “waiting for the Friendship Church to come and pick him up and take him to a shelter.” Warren is the stereotypical homeless person normally overlooked by the average person walking around in the famous Beale Street area.

Lt. Sandra Marshall (center) of the Memphis Police Department talks to Robert Warren (seated), a homeless man in Memphis, Tennessee, as Lt. Felix Calvi looks on during the first day of a citywide sweep of the homeless population in the city in December 2009.

Brad Watkins, organizing coordinator for the Mid-South Peace and Justice Center, said that city government keeps trying to find ways of pushing homeless people out of Memphis’ business district. For example, a proposal now being considered would prevent sales of single cans of beer within the city’s Business Improvement District, but Watkins said this will only push people with alcohol addiction into surrounding neighborhoods, increase the sale of cheap liquor instead of beer and benefit chain stores just across the boundary line that is being considered as opposed to the mom and pop stores inside the zone.

He said that the city is taking a few positive steps for the homeless, such as trying to get a more accurate count of homeless people. At the same time, he said, police continue surveillance, using cameras, in front of Manna House, where homeless people can get food.

Lt. Felix Calvi of the Memphis Police Department stands next to Robert Warren, a homeless man. They are waiting for a local shelter to come and pick Warren up during the first day of a citywide sweep of the homeless population ordered by the mayor’s office.

He said further that many homeless people are not seen camped on the streets because they have taken up occupancy in abandoned homes that abound in the Memphis. A major problem contributing to homelessness, he said, is that, because of inadequate funding, the Federal Section 8 housing subsidy program in Memphis has a four-year long waiting list. “It is very shameful,” he said, and “it is a national problem.”

Disappear?

Arresting or moving homeless people to shelters would quickly overwhelm the private nonprofit facilities and the jails. Most homeless people would find themselves back on the streets within a few days. June Averyt with the nonprofit group Door of Hope explained that sweeps won’t fix the problem. “Are they supposed to disappear? Fall off the face of the earth? What they need are the services,” Averyt said in a recent interview with the local paper.

There appears to be no clear, comprehensive plan in Memphis other than pressuring homeless people to creep deeper into the background of the city’s fabric until it’s safe to creep back out. The status quo of Memphis’ “homeless problem” has been a nuisance issue, but the dark cloud approaching on the horizon, the tsunami of need of the new homeless, is really what Memphis should be reacting too, particularly as the cold of winter settles in.

Politics as usual keeps many of these people in check, often stuck in family shelter situations that are just getting more and more crowded. The mayor’s office pushes hard when under pressure from the public or business owners to do something and then retreats when painted as heartless and militant in the media.

The career homeless in cities like Nashville and Memphis are also feeling the growing pressure of more people entering their ranks and vying for services. There are now families, teens and the unemployed, who have run out of options, entering the ranks of no place to call home. Tent cities and alternative communities are seeing incredible growth that also brings in a spotlight that is focusing attention on people that otherwise preferred to survive in the shadows of social blindness and disregard.

(This is part of an ongoing series about the new homeless in America.)

Matching Opportunity Extended: Please support Truthout today!

Our end-of-year fundraiser is over, but our donation matching opportunity has been extended! All donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar for a limited time.

Your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. Your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. As Trump attempts to silence dissenting voices and oppositional nonprofits, reader support is our best defense against the right-wing agenda.

Help Truthout confront Trump’s fascism in 2026, and have your donation matched now!