Part of the Series

Voting Wrongs

No one who was cognizant during the 2000 election will ever forget it. Hanging chads, pregnant chads, dimpled chads. Butterfly ballots. Men in suits. Nepotism. Voter purges. Bush v Gore.

Secretaries of state around the nation were breathing sighs of relief that it didn’t happen in their states. Poor Katherine Harris.

Nowhere was that sigh more audible than in Georgia, which had an even higher rate of undercounted votes than Florida (3.51 percent versus 2.9 percent). Georgia Secretary of State Cathy Cox was understandably relieved that the focus was on Florida that year, and she became determined to eradicate any possibility that Georgia might be next.

The cliché that the cure can be worse than the disease aptly describes the steps that many states have taken since that time, ostensibly in the pursuit of improving elections.

Georgia was at the head of the pack. By 2001, it had established a commission that made recommendations to the governor and legislators regarding a touchscreen electronic (DRE) system to be implemented uniformly throughout the state. Diebold was chosen from among several options, even though it wasn’t the most cost-effective bid, but the now-notorious revolving door between Diebold (now ES&S) and Georgia’s state government was just kicking in.

Georgia would be the first in the nation to hand management of its entire state’s elections over to a partisan, private company. Nothing could go wrong with this, right? Especially with untested voting equipment that leaves absolutely no paper evidence of voters’ intent, or even the possibility of audits or meaningful recounts.

But Georgia did not act alone. Enabled by the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA), other states responded with similar knee-jerk reactions and replaced their voting systems with unproven technology. HAVA’s newly-founded Election Assistance Commission had not yet fully established the voluntary standards and guidelines for election technology, so states were already spending the funds and interpreting the rules variously. By the 2004 presidential election, nearly one-third of registered voters were expected to cast their votes on unaccountable touchscreen computers.

Perhaps Americans should thank the Russians for finally jolting the nation out of its denial about the vulnerabilities of electronic voting systems, and the mess in which the U.S. finds itself almost 20 years later.

The genius of unaccountable systems is that, short of a court-mandated order, rigging, hacking or errors remain undetectable. Even so, many problems have always been obvious to voters: selected votes “jumping” on screens from one candidate to another, screens freezing, units randomly shutting down. These common failings cannot be hidden. How can voters trust that their votes were recorded correctly? Or even recorded at all?

As states such as Georgia bulldoze over these concerns, the nation careens into another possible election debacle, leaving voters fearing that the results of the 2020 election could lead to doubt and rancor.

Rinse, Repeat…

In 2018 a new commission was convened by Georgia’s then-Secretary of State Brian Kemp to review options for the next election system. The commission heard testimony from the cybersecurity community and election integrity activists who strongly urged them to change to a hand-marked, optical-scan paper ballot system with risk-limiting audits (and one machine per precinct for accessibility compliance). Cybersecurity experts advised that any computer that comes between a voter and her/his vote introduces the possibility of hacking or error. Machines malfunction. Audits cannot be performed without trustworthy recorded votes.

Despite that advice, but with the competing “help” of corporate lobbyists, the commission recommended a ballot-marking device (BMD) system. The state legislature, which had also heard compelling arguments recommending a hand-marked paper ballot system, quickly moved ahead to adopt a BMD system, potentially costing $150 million.

The Dominion BMD system Georgia selected is barely an improvement over the old DRE one. Basically, it’s another touchscreen computer system with a newer operating system, paper printouts and other tweaks, but is still vulnerable to attack. Secret, proprietary software and hardware are still at the heart of the system. Public oversight of the chain of command of the vote is still broken.

All Paper Ballots Are Not Equal

Voters are being lulled into a false sense of confidence that all is now well because the new BMDs provide paper printouts.

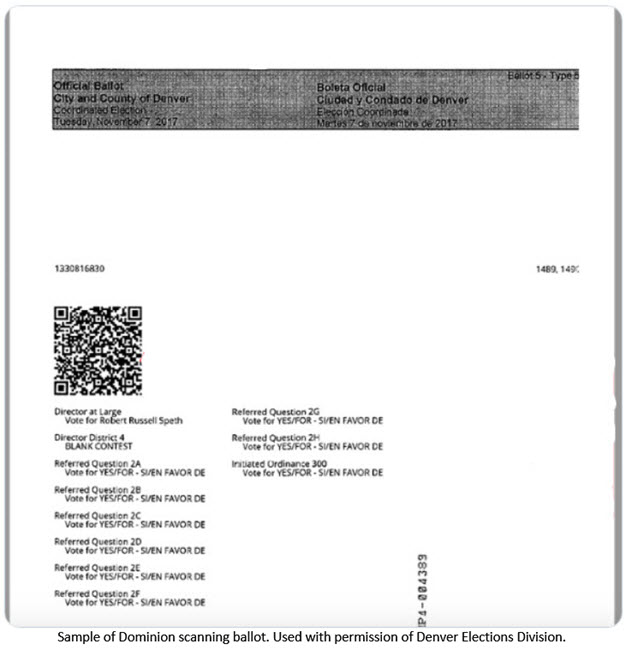

This paper feature is insidious for many reasons. First, it should not be called a paper ballot. Unfortunately, that is the vernacular that has been adopted by the media. An official name was coded into Georgia law: scanning ballot. A scanning ballot is not a full-face ballot that contains the names of all candidates and wording of initiatives. It is simply a summary list of voter selections that also contains a proprietary QR barcode that allegedly encodes what’s on the list. The QR barcode, not the human readable portion, is what is tabulated. Meanwhile, the human readable portion is barely readable: apart from the dearth of information it provides, the summary list is printed in tiny font.

It is unreasonable to burden voters with responsibility for identifying machine errors in the tiny print, especially with a long list of candidates and ballot measures. It is even worse to expect them to trust that a barcode accurately reflects what is in those lists. Research indicates that most voters do not take sufficient time to review these summary lists; many do not even glance at them before they are tabulated.

Finally, cognitive limitations, such as imperfect recall, prevent accurate and complete verifiability. This system takes longer to complete, creating longer lines at polling places.

Georgia’s Race to the Bottom

As states focus on getting every legitimate voter registered and equipped to vote, they must not take their eyes off the biggest prize of all: the technology undergirding the actual vote counts.

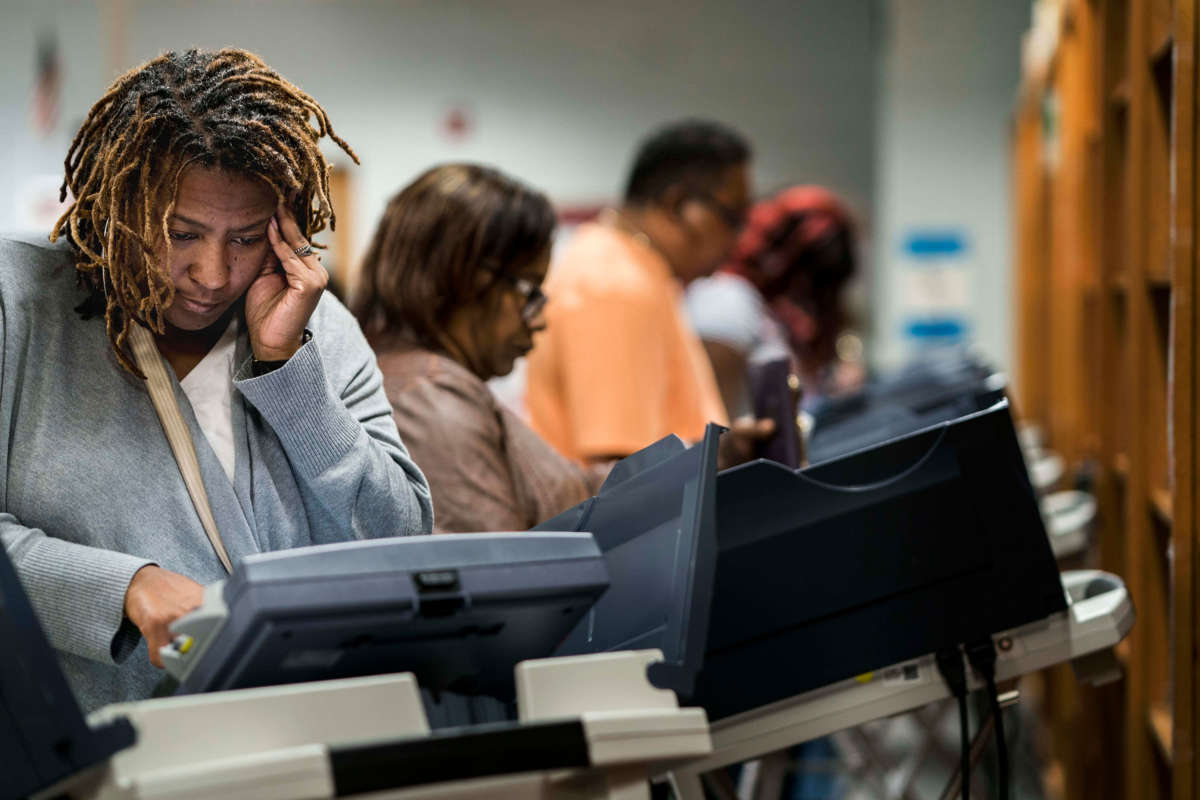

Voter suppression takes many forms. Georgia has earned itself a reputation as the epicenter of voting nightmares, especially for voters of color. Notorious as one of the first states to require photo voter ID, it continues to make news with its voter purges, polling location closures and numerous other affronts. It is hardly surprising that Fair Fight Action rose from the incompetence and malfeasance that Stacey Abrams perceived as a candidate for governor in 2018 against the man then in charge of elections, Secretary of State Brian Kemp.

The role that Georgia’s unverifiable electronic voting system has played in this suppression cannot be understated. Because entire elections can be rigged without detection, no one can be certain that any election in the state of Georgia since 2002 accurately reflected the will of the voters. Even with that lack of transparency, enough has been exposed to paint a dismal picture of the system: the state’s Election Center server was breached in 2016; confidential voter information for the entire state has been exposed; the state wiped election data from the state server just days after a lawsuit was filed requiring the data for examination; an unexplained undervote of possibly 127,000 votes occurred in the lieutenant governor’s race in 2018; the 2018 ballots were built on home equipment by corporate employees.

If this is what is known, imagine the jaw-dropping truth lurking in proprietary cybermemory, and what, if insecure voting technology continues to proliferate, it portends for the future of our democracy’s most treasured ritual.

As other states and districts consider different voting technologies, they would do well to avoid Georgia’s example. Most of the new BMD systems offer little confidence that matters will improve. They are within the purview of private companies whose trade secrets give them greater access to the voting process than voters are entitled to. They are still computer-based systems, with all the vulnerabilities implicit with computers. The ones with barcode summary lists fall far short of providing adequate voter verifiability.

It is enough to make voters long for the days of hanging chads.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $250,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.