Accurately assessing the fruits of the Iranian Revolution is crucial to understanding Iran today.

(Photo: Wikimedia)February 2014 marks the 35th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution – an epochal event whose ultimate significance remains unknown. Regarded as the “last great revolution,” one that overturned Iran’s political, economic, social and cultural order, Iranians will endlessly assess and debate its aftermath, up to and including the clerical rule that soon followed in its wake. Yet, few will regret the revolution itself. Even among those who most vigorously dissent from the Islamic Republic’s rule, the revolution remains a source of intense pride – a living testament to the will and determination of a people to break the chains and assert their independence.

(Photo: Wikimedia)February 2014 marks the 35th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution – an epochal event whose ultimate significance remains unknown. Regarded as the “last great revolution,” one that overturned Iran’s political, economic, social and cultural order, Iranians will endlessly assess and debate its aftermath, up to and including the clerical rule that soon followed in its wake. Yet, few will regret the revolution itself. Even among those who most vigorously dissent from the Islamic Republic’s rule, the revolution remains a source of intense pride – a living testament to the will and determination of a people to break the chains and assert their independence.

Even among those who most vigorously dissent from the Islamic Republic’s rule, the revolution remains a source of intense pride – a living testament to the will and determination of a people to break the chains and assert their independence.

In the United States, however, the Iranian Revolution has a much different meaning. It signifies, first and foremost, the fall of arguably the US’s closest ally in the Middle East – Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the shah – and the advent of an assertive and revisionist state – the Islamic Republic of Iran – which had little regard for maintaining America’s privileges in the region. Far from sympathizing with Iranians’ yearning to cast off the yoke of dictatorship, the United States saw in the revolution little more than a baffling, chaotic outburst of religious fanaticism – made all the more threatening several months later when revolutionary students seized the US embassy in Tehran following the deposed shah’s admittance to the US for medical treatment.

For the past three and half decades, these events – and the political and media reaction to them – have catalyzed Americans’ perception of Iran, its government and its people. Describing media coverage of Iran at the time of the hostage crisis, the late Edward Said perceptively noted, “Clichés, caricatures, ignorance, unqualified ethnocentrism and inaccuracy were inordinately evident … with the result that the distinctive continuities and discontinuities of Iranian revolutionary life never emerged.” For example, The New York Times‘ reporting, according to Said, formed “a collection of attitudes displayed for the benefit of suspicious and frightened readers.”

In other words, those in the United States saw events in Iran in 1979 through their own distinctive prism, which was far removed from – and often quite antagonistic to – the very real aspirations and grievances of a revolutionary people. It would be hard to argue that much has changed in the interim: 35 years of demonization, distrust and denial have shaped US discourse regarding the revolution and its heir, the Islamic Republic. Consequently an honest and dispassionate assessment of the revolution’s myriad and measurable achievements has proven elusive, if not altogether impossible. Meanwhile, exposition of its shortcomings and unforeseeable consequences (like Iraq’s invasion in 1980) has been routinized to the point of exaggeration and exploitation.

Even now, as we pass the revolution’s anniversary, the US press privileges and amplifies those Iranian voices that reflect back what Americans have been led to believe about Iran and its revolution. They speak contemptuously of the 1979 upheaval, either regretting its very occurrence or bemoaning the lowly place it has brought Iran in the global order. For the most part, too, their claims are allowed to pass without challenge or substantiation – the prevailing narrative beating out once more the inconvenience of historical fact. Fair appraisal, it seems, proves as rare in 2014 as it was in 1979.

Rewriting History

Two recent cases underscore this phenomenon. In October 2013, Afshin Molavi, a fellow at the New America Foundation and Johns Hopkins’ Foreign Policy Initiative, declared that, while Iran’s revolution “reordered regional and global geopolitics, and spawned hope, inspiration, joy, terror, destruction, despair and disenchantment .. [t]he one thing it didn’t do was improve people’s living standards.”

Seconding the claim, Iran-born author, Camelia Entekhabifard, wrote of the legacy of the Iranian Revolution in February 2014 in Al-Jazeera English:

“Ayatollah Khomeini promised his followers free electricity and cash from oil revenues. … Now, poverty, unemployment, inflation and a high cost of living are all what most people, I’ve spoken to, believe the revolution has brought them.”

Then, in a New York Times piece marking the revolution’s anniversary on February 11, she doubled-down on her contention: “In an attempt to eliminate what he perceived as Western corruption, Ayatollah Khomeini mismanaged the economy, setting back development and widening the gap between rich and poor – while engaging in a devastating eight-year war with Iraq.” (Entekhabifard conveniently thrusts to the side two basic facts that undercut the premise of her argument: first, Iran has been living under US-imposed sanctions since 1979, and second, Iraq was the aggressor during the Iran-Iraq War, as the UN secretary-general pointed out in a report in 1991.)

With regard to life expectancy, health, education and living standards – “Iran has made considerable progress in human development when measured over the past 32 years.”

For both authors, the Iranian revolution – despite whatever promises it may have held – has left Iranians despondent and desperate, worse off than where they started in 1979. But this tale, tall as it is, confounds fact and fiction, ignores historical data on Iranians’ living standards, and thus rewrites history. Furthermore, perpetually casting the revolution as merely a backward embrace of medieval theology and a stubborn rejection of modernization and development does a great disservice to the reality (and messiness) of the Islamic Republic and forces us to question the ultimate integrity of the writers themselves.

Decades of Development

It doesn’t take long, for instance, to undermine Molavi’s claim that the Iranian revolution failed to “improve people’s living standards,” nor Entekhabifard’s contention that the Islamic Republic “setback development.” In its 2013 report, for instance, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which measures long-term societal progress in human development around the world, assessed that – with regard to life expectancy, health, education and living standards – “Iran has made considerable progress in human development when measured over the past 32 years.” It did this while under constant economic siege and military threat.

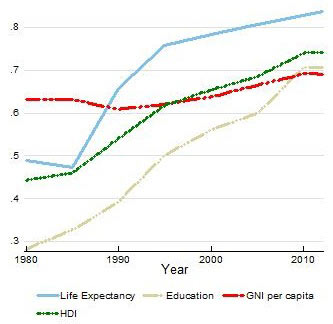

Not only is the Islamic Republic of Iran considered a location of “High Human Development,” according to the UN’s Human Development Index (HDI), but “between the years 1980 and 2012, Iran’s HDI value increased by 67 per cent,” virtually doubling the annual gains of other countries in the same category and more than twice the global average. The UN notes that “from a human development standpoint – during the period 1980-2012, Iran’s policy interventions were both significant and appropriate to produce improvements in human development.” In other words, Iran’s gains are not haphazard luck but, rather, a direct result of specific policies of the Islamic Republic.

HDI trends for the Islamic Republic of Iran since 1980 (United Nations Development Programme)

HDI trends for the Islamic Republic of Iran since 1980 (United Nations Development Programme)

The media have been virtually silent about the ravages of the Shah’s dictatorial rule, the brutality of his CIA and Mossad-trained secret police force, SAVAK, and the surveillance, corruption, and torture that thrived during his reign.

This works to undermine the predominant narrative – subtly hinted at in both authors’ pieces – that were it not for the shah’s illiberal policies at home, which alienated Iranians, he could have followed through on his modernization scheme and left Iran in a much better place than it finds itself today. (This narrative may likewise explain why the media has been virtually silent about the ravages of the Shah’s dictatorial rule, the brutality of his CIA- and Mossad-trained secret police force, SAVAK, and the surveillance, corruption and torture that thrived during his reign. Even today, accounts of the shah’s Iran border on the hagiographic – his social policies widely praised for the “modern” attitudes that they are said to resemble. While Entekhabifard, for instance, laments what she deems the destruction by the clerical leadership of Iran’s pre-revolution “pluralistic society,” few recount, as scholars Shahrzad Mojab and Amir Hasspour do, that “during the entire rule of the Pahlavi dynasty, the possession of Kurdish, Turkish or Baluchi publications, gramophone records or even a handwritten poem was proof of ‘secessionism’ of political prisoners.” The benefits of the shah’s “pluralism,” it seems, were very narrowly targeted.)

In his 1989 study, Social Origins of the Iranian Revolution, Misagh Parsa described the stark living conditions faced by Iran’s impoverished citizens pre-1979:

“During the 1960s and 1970s, Iranian society was characterized by housing shortages, land speculation, and considerable social and economic inequality. The government’s rushed development policy and its strategy of serving the interests of the upper class and wealthier groups were largely responsible for these problems. …

“Despite increased spending, the housing shortage remained unalleviated for the working classes and the poor. Part of the reason was that most government investments financed the construction of military and “national” buildings.”

Parsa adds, “On the eve of the revolution, as many as 42 percent of the inhabitants of Tehran lived in inadequate housing.” Furthermore:

“Whereas 80 percent of the city budget was allocated to provide services for the wealthy inhabitants of northern Tehran, shantytowns lacked running water, electricity, public transportation, garbage collection, health care, education, and other services. The contrast between urban shantytowns and rich high rises was an embarrassment to a regime that had promised the advent of a ‘great Civilization.’ As shantytowns proliferated, the government declared them illegal. Eventually, in mid-1977, the government sent bulldozers to demolish a number of shantytowns in large cities, including Tehran.”

The Islamic Republic managed to pull together one of the most impressive rural development schemes in modern history.

Outside of Tehran and other major cities, the situation was even worse. In the rural provinces, basic services proved absent, literacy rates remained at appalling lows, health care was largely unavailable, and schooling for children was dismal. As Ervand Abrahamian noted in his magisterial study, Iran Between Two Revolutions, an International Labor Office report dated from 1972 called Iran “one of the most inegalitarian societies in the world.” Whatever his intentions, then, Iran’s self-styled Ataturk proved himself remarkably incapable of, or simply disinterested in, meeting the needs and demands of his people.

On the other hand, the Islamic Republic managed to pull together one of the most impressive rural development schemes in modern history, despite being under savage attack by Western-backed Iraqi forces and economic assault from the world’s leading power. In doing so, too, the Islamic Republic triggered a profound cultural revolution that enlisted women in the fight to remake society from the ground up and thus undermined the tethers that had for so long tied them to their religious families – a fact that scholars of Iran’s gender politics are beginning to uncover.

We see its effects when we look at the hard data. In the two decades between 1984 and 2004, the poorest 25 percent in rural areas saw their access to basic electricity increase from 37 percent to 94 percent and to piped water from 31 percent to 79 percent, highlighting the substantially increased access to basic services for Iran’s rural poor.

Iranians live longer and healthier lives than they did under the Shah, having added over two decades to their average life expectancy (up from 51 years to 73 years).

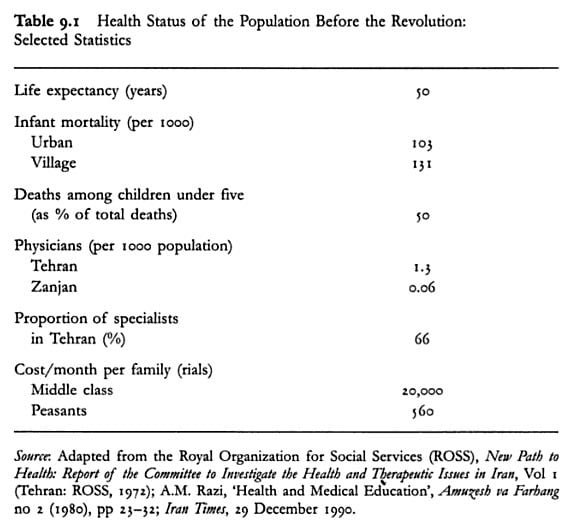

Improvements in health care are similarly impressive. During the shah’s reign, access to health care was deplorable, with rural populations suffering the most. In addition to a dearth of both hospitals and doctors, Parsa reveals that “infant mortality in rural areas was 120 (per 1,000 live births), one of the highest in the world. … Malnutrition was prevalent in many parts of the country, and anemia was almost universal.”

“The real problem,” Parsa concludes, “was the regime’s failure to commit sufficient resources to meet society’s needs. Instead, resources were spent, or rather wasted, on military buildup” – a fact overlooked in the hype and hysteria over the Islamic Republic’s meager outlays to its military apparatus.

Today, however, Iranians live longer and healthier lives than they did under the Shah, having added more than two decades to their average life expectancy (up from 51 years to 73 years). Infant, maternal and neonatal mortality rates have dropped dramatically. For every 100,000 live births in Iran today, only 21 women die from pregnancy-related causes. (The average for other High HDI countries is 47.)

“Poliomyelitis has been reduced to the point of near-eradication and the coverage of immunization for children and pregnant women is very extensive,” reports UNICEF. “Access to safe drinking water has been provided for over 90% of Iran’s rural and urban population. More than 80% of the population has access to sanitary facilities.”

More than 85 percent of Iran’s rural and vulnerable populations now have free access to primary health care services through an impressive system of “health houses,” which have been described by the World Health Organization as an “incredible masterpiece” and replicated for disadvantaged communities in the Mississippi Delta region.

Literacy is practically universal, thanks to the extensive literacy programs put in place soon after the revolution.

While commentators – such as Entekhabifard – are quick to point out that Iran still experiences a wide rural-urban gap in income inequality, they fail to note, as Djavad Salehi-Isfahani has, that since the end of the Iran-Iraq War, “poverty has declined steadily to an enviable level for middle-income developing countries.”

Iran’s literacy programs also have proven a boon. In 1975, 68 percent of all Iranian adults were illiterate; only 35 percent of women were literate; and literacy rates in Iran’s poorest provinces typically hovered around 25 percent. Today, however, literacy is practically universal, thanks to the extensive literacy programs put in place soon after the revolution (none more significant than the Literacy Mobilization Organization, which was an outgrowth of the efforts of leftist students in the period 1979-81). Women and the rural poor shared these gains. That is why, for instance, more than 60 percent of college and university students today in Iran are women, many of them studying in the sciences.

Only a further transformation in cultural values can replace the deep misogyny that underpins much of the leadership’s attitude toward women.

Claims that the Iranian Revolution marked an ideological rejection of modernization are even more difficult to substantiate considering that, as the New Scientist reported in 2010, “scientific output has grown 11 times faster in Iran than the world average, faster than any other country.” Moreover, scientific “publications in nuclear engineering grew 250 times faster than the world average – although medical and agricultural research also increased.” And, far from being an illiterate and backward ruling elite, Iran’s leaders tend, on the whole, to be highly educated: that Iran’s Cabinet employs more American Ph.D.s than Barack Obama’s White House made for a “fun fact” not long ago.

The Revolution, Continued

Acknowledging these basic facts (of which there are many more) does not, by any means, condone the very real repression that exists in the Islamic Republic, nor the tension in values inherent in the Islamic Republic’s very name. It is perfectly true that Iranians face severe limitations on their ability to vigorously engage in political, social and cultural life; that, despite the rise in women’s health and education standards, gender inequities remain firmly rooted in the Islamic Republic and only a further transformation in cultural values can replace the deep misogyny that underpins much of the leadership’s attitude toward women; that access to information in Iran is restricted because of government censorship; and that upholding human rights remains critical to improving the Islamic Republic’s reputation at home and around the world.

Ignoring what the Islamic Republic has done right imperils efforts to create a more promising future for all Iranians.

But, fictionalized representations of the Islamic Republic perform no service to Iranians, who struggle for a more just and equitable public space in their beloved country, and disrespects those who, after deposing a puppet dictator, set about improving the lives of their fellow citizens. In fact, as discerning scholars have noted, much of the recent activism in Iran – including the Green Movement – is thanks to a broadened middle class, “whose empowerment stems from the developmental push of the Islamic Republic over the past two decades.” In other words, the growth of Iran’s reform movement can be traced back “in part [to] the modernizing efforts of the post-revolutionary state itself.” That is not an analysis that is heard all too much in popular discourse about Iran.

Besides the damage done to an honest appraisal of Iran’s history, a failure to acknowledge the very real achievements of the Islamic Republic – including the way it rendered visible entire segments of the population that had before been scorned and denigrated (the rural poor, the religious classes, etc.) – risks exacerbating the rampant ignorance about the country here in the United States, serving only to further cultivate the damaging Manichean view of Iran so prevalent in our politics and press.

Moreover, ignoring what the Islamic Republic has done right imperils efforts to create a more promising future for all Iranians – a lesson unlearned and thus doomed to go unheeded. Accurately assessing the fruits of the Iranian Revolution not only respects the value of truth but also the will and determination of the Iranian people to throw off the shackles of autocracy and continue their long revolution.

Help us Prepare for Trump’s Day One

Trump is busy getting ready for Day One of his presidency – but so is Truthout.

Trump has made it no secret that he is planning a demolition-style attack on both specific communities and democracy as a whole, beginning on his first day in office. With over 25 executive orders and directives queued up for January 20, he’s promised to “launch the largest deportation program in American history,” roll back anti-discrimination protections for transgender students, and implement a “drill, drill, drill” approach to ramp up oil and gas extraction.

Organizations like Truthout are also being threatened by legislation like HR 9495, the “nonprofit killer bill” that would allow the Treasury Secretary to declare any nonprofit a “terrorist-supporting organization” and strip its tax-exempt status without due process. Progressive media like Truthout that has courageously focused on reporting on Israel’s genocide in Gaza are in the bill’s crosshairs.

As journalists, we have a responsibility to look at hard realities and communicate them to you. We hope that you, like us, can use this information to prepare for what’s to come.

And if you feel uncertain about what to do in the face of a second Trump administration, we invite you to be an indispensable part of Truthout’s preparations.

In addition to covering the widespread onslaught of draconian policy, we’re shoring up our resources for what might come next for progressive media: bad-faith lawsuits from far-right ghouls, legislation that seeks to strip us of our ability to receive tax-deductible donations, and further throttling of our reach on social media platforms owned by Trump’s sycophants.

We’re preparing right now for Trump’s Day One: building a brave coalition of movement media; reaching out to the activists, academics, and thinkers we trust to shine a light on the inner workings of authoritarianism; and planning to use journalism as a tool to equip movements to protect the people, lands, and principles most vulnerable to Trump’s destruction.

We’re asking all of our readers to start a monthly donation or make a one-time donation – as a commitment to stand with us on day one of Trump’s presidency, and every day after that, as we produce journalism that combats authoritarianism, censorship, injustice, and misinformation. You’re an essential part of our future – please join the movement by making a tax-deductible donation today.

If you have the means to make a substantial gift, please dig deep during this critical time!

With gratitude and resolve,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy