Truthout is a vital news source and a living history of political struggle. If you think our work is valuable, support us with a donation of any size.

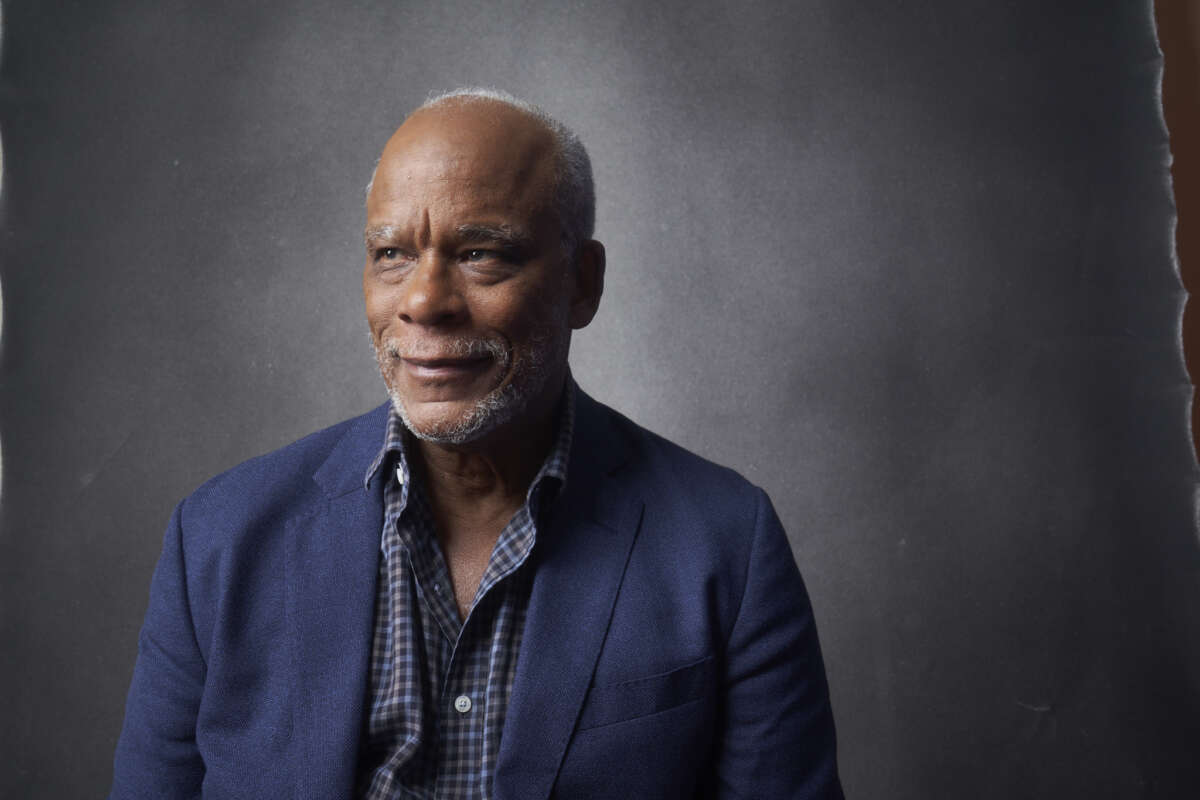

Since 1989 Oscar-nominated filmmaker Stanley Nelson has been among the leading chroniclers of Black liberation and civil rights struggles in the U.S. Some of the documentaries Nelson has directed and produced, such as 2003’s The Murder of Emmett Till, 2021’s Tulsa Burning: The 1921 Race Massacre and the 2021 short Lynching Postcards:‘Token of a Great Day’ — about souvenir postcards that commemorated some of the 4,000-plus lynchings of African Americans from 1880 to 1968 — depict the horrors of Jim Crow. But Nelson also documents Black communities’ heroic resistance to slavery, segregation and racism in films including 2022 biopics about abolitionists, Harriet Tubman: Visions of Freedom and Becoming Frederick Douglass.

2010’s Freedom Riders is about the nonviolent crusade to desegregate interstate busing, for which Nelson won Emmy Awards, and 2014’s Freedom Summer recounts the movement schools and voter registration drives of 1964 Mississippi. Nelson boldly tackles Black Power in 2015’s The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, which was Emmy-nominated, and in the gripping 2021 prison uprising saga Attica, Academy Award-nominated for Best Documentary.

Now Nelson is back with a new nonfiction film that zooms in on a recurring theme interwoven through many of his productions: police violence and brutality against Black people. Sound of the Police compellingly, comprehensively catalogues police abuses of power. In only 85 minutes, Nelson and co-director Valerie Scoon render a historic overview of the clash between police and Black people from the pre-Civil War slave patrols and Fugitive Slave Act through the Jim Crow era and civil rights movement, up to today’s Black Lives Matter struggle against police brutality. The documentary also probes the role that police “fraternal associations” play in protecting officers accused of using brutal and deadly force against unarmed Black people. The soundtrack features sharp hip-hop music, including Ice Cube’s “Who Got the Camera” and KRS-One’s “Sound of Da Police,” which inspired the documentary’s title.

In this exclusive interview with Truthout, Nelson discusses the history of policing, the role of copaganda in perpetuating police violence and defunding the police.

Ed Rampell: What is the legacy of slave patrols and the Fugitive Slave Law, and how does this history impact contemporary policing?

Stanley Nelson: It’s really important that you understand the history of policing, that problems between African Americans and police didn’t start with George Floyd, didn’t start with the Black Panthers, didn’t start with Eric Garner. In many ways the modern police, as we know it, came out of the slave patrol. In early America, the slave patrols were some of the first police forces. So, that’s very significant.

And then the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 made it so every African American was now a suspect. It was the duty of every American, especially the police — not only in the South, but in the North — to turn in anybody they suspected of being a fugitive slave. That meant every African American was suspect and every African American could be turned into the police and be represented by white folks as being suspicious of being [a runaway slave].

In the film, we draw the comparison to what we’ve come to know as “Karens” today. Karens are a phenomenon where people call what they feel to be their police on African Americans especially.

How does this affect the way Black people view police today?

A poster in Boston in the 1850s said: “Warning To our Negro citizens: Do not trust the police. They are not your friend. They are working with slave catchers.” And that distrust is from the beginning. Think about being there in 1850. And it’s come down to modern days in various ways so that in many instances, African Americans cannot trust the police in the same way that our white citizens can trust the police. The way that African Americans rightly view police is very different from the way white people are afforded the opportunity to see the police.

Tell us about the power of police unions and what their role is vis- à-vis rules, laws and enforcement regarding police excessive use of force?

That was one of the things that’s really important that we included in the film. So many times, the role of police unions and benevolent associations etc., are forgotten, are not highlighted. But police unions are there pretty much just to defend the police. If you can tell me an instance when a police union goes against anything that a police officer does, you’d be doing really well.

Also, the police unions have a really big bully pulpit. They’re speaking from an elevated status. They’re believable. They’re the police; they’re the police unions, and they say this guy is a bad guy … and we’ve seen it over and over again. We have clips in the film where Eric Garner is being strangled and he’s telling the officer, “I can’t breathe! I can’t breathe!” And the head of the police union in New York says, “Well, if he can speak, he can breathe.” Yet, he was choked to death.…

The police unions negotiate contracts where the police are not held [personally] liable. They negotiate contracts that are very, very, very liberal to anything that police do. They negotiate contracts where one police department can’t report to the other that a cop just got fired, that a cop will get fired and thrown off of the police force for some action and he’ll get hired by another police force right next door. Police unions have become really bad actors. We wanted to make sure that we understood the role of police unions in defending the actions that police officers commit.

What is “copaganda” and what is its role?

There are so many things that are propaganda. One that we talk about in the film are cop shows. We don’t think about “Law and Order,” “Hawaii Five-O” and “Dragnet” as propaganda, but they are. We talked to an ex-police officer who, while he was a police officer, wrote half of the scenes of the “Dragnet” show in the ’50s and early ’60s. The shows were actually written by a cop and the police department actually got approval of the scripts. So, is that propaganda? Yes!

In Sound of the Police, we have a montage of maybe 50-60 cop shows over the years. If you look at your TV Guide tonight, count the number of cops shows on the major networks. I would say that that’s propaganda. In the cop shows, the cops are always trying to do right, trying to protect and serve the public, all citizens. It’s propaganda for the police. The reality for African Americans is very, very different.

What do you think of the fact that enormous parts of state, city and federal budgets go to “security” in the form of police, military and intelligence agencies, instead of funding for essential services for ordinary people?

There’s a limited amount of resources, no matter how great the resources are. And we spend a disproportionate amount on the police force and military, and it means we have less to spend on other things. Less to spend on education, on transportation, on the safety net for the people, on the arts. That’s because there’s a disproportionate amount of money spent on law enforcement of one type or another.

What do you think of calls to defund or abolish the police?

It’s not very simple in my mind. We really have to look at defunding the police, which can mean total defunding or just a little less money. One of the things that is said in the film is that we really don’t need a cop with a gun to handle every situation. It’s probably not the best in every situation. It probably hurts the situation, escalates the situation if you come in with a gun….

All of those things should be studied because it’s not working as it is. Whether it’s defund or abolition or reform, something has to be done. I don’t think anybody would tell you: “Yeah, this is great, it’s working really well as it is.” I know a vast majority of African Americans would say that, a number of white Americans are seeing and knowing that. And a number of police are seeing that it’s not working the way it should be and could be.

Sound of the Police observes that some Black police officers also engage in brutality against African Americans. Why?

I think it’s the culture, the institution — it’s not the individual. One of the things people thought in the ‘60s was: “Oh, we should have more officers of color. More officers that look like the community they were patrolling. Things would improve.” They have not. If you’re African American or Asian or Latino and you join the police, the odds are that you’re going to become a part of that culture that’s already established there. And that’s been proven out through statistics and other things.

Who are some of the victims of police brutality and murder you highlight in your film?

We start out with the case of Amir Locke, who was a young man in Minneapolis and the police broke into his apartment in the middle of the night. Within nine seconds he was shot dead.

Other lesser known cases: Keyon Harrold and his son were accosted in a New York hotel by a “Karen” who just thought that, for some reason out of nowhere, that his young son, Keyon Jr., had stolen her phone for no reason…

Another incident that we highlight is at a mall in New Jersey where a white [kid] and a Black kid are having a fight and the cops come and throw the Black kid on the ground and handcuff him and let the white kid just sit there. The cops had no reason to feel that one kid was the instigator and the other wasn’t, except for the race of the kid. We also talk about other cases that have become famous: Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, and others.

How have your own personal interactions with police been?

My own personal interactions [laughs] — like so many people, I’ve been stopped and frisked and harassed for no reason. Probably more important at the moment is I have a 24-year-old son. When he was a teenager growing up in New York City, what I told him is: “You want to have the least amount of interactions with the police as you can. If you’re on one corner and the police are on another and they’re walking towards you and you can kinda mosey across the street to be on the other side of the street [laughs], you probably should. Because there’s nothing good that can come from a confrontation with the police and you probably want to avoid as much contact with the police as you can.”

So, you gave your son “the talk.” When you were a youth, were you given the talk?

…As I became a teenager and 20, 21, me and my friends realized that we were stopped a lot. As you grow older as an African American, you tend to be stopped and harassed less. But when you’re 16, 17 and 18, you are harassed by the police all the time, all the time. It’s almost like they can do it, they can do it with impunity and so they do. As one guy talks about in the film, when he was a teenager police threw all of his friends and him down on their faces while they’re playing basketball and just continued to harass them for 20 minutes. It’s like entertainment for the police. It just increases the animosity between African Americans and the police.

What is something you learned that may have surprised you when you were making Sound of the Police?

One of the things I learned in making the film is that negative relationship between African Americans and the police has a long history in this country. It’s not something new. We show [archival photos of] people being lynched — their hands have on police handcuffs. Not only did the police not stop the lynching, but the police lent their handcuffs to the lynchers. That was just part of how it was. Someone says: “Throughout the history of this country when the police often had to choose a side, this side was always with white people.”

What’s next for Stanley Nelson?

We’re working on a bunch of things. We’re just starting a film on medical racism for [PBS’s] “NOVA.” We’re working on a film for Lincoln Center about the destruction of the neighborhood, San Juan Hill, that was there until they built Lincoln Center. The building of Lincoln Center wiped out an entire community. We’re just starting a film that will hopefully be a lot of fun, on funk music.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we have a goal to add 242 new monthly donors in the next 48 hours. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.