Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

Translated by Danica Jorden.

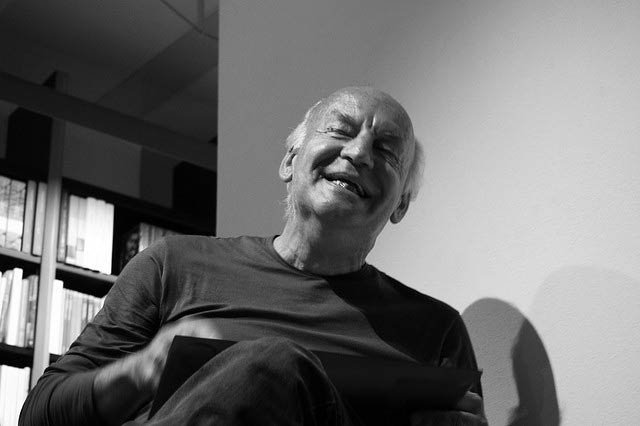

The Uruguayan writer and journalist, author of emblematic books such as Open Veins of Latin America, Memory of Fire and The Book of Embraces, died at 74 in Montevideo, Uruguay.

Eduardo Germán Hughes Galeano was born in Montevideo on September 3, 1940, the son of EduardoHughes Roosen and Licia Ester Galeano Muñoz, whose last name he took as a writer and journalist. When he was a teenager, he began publishing cartoons in El Sol (The Sun), a socialist newspaper in Uruguay, under the pseudonym “Gius.” He also worked as a laborer in an insecticide factory and signboard painter, among other jobs, despite coming from an upper-class family.

He began his career as a journalist in the early 1960s, as editor of the weekly Marcha (March) and the daily Época(Epoch). At the time of his country’s coup d’état, he was imprisoned, and later set himself up in Argentina. A decade afterwards, he became director of cultural and political magazine Crisis, founded by Federico Vogelius (1919-1986). “It was a great act of faith in the solidary and creative human word…. To believe in the word, in that word, Crisis chose to be silent. When the military dictatorship prevented it from saying what it needed to say, it refused to continue speaking,” he said when it closed in August 1976.

That same year, his name made the “wanted” list of the Argentine military dictatorship, presided over by Jorge Rafael Videla, and Galeano travelled to Spain. There, he wrote the Memory of Fire trilogy (The Births in 1982; The Faces and The Masks in 1984; and The Century of Wind in 1986), in which he revisited the history of the Latin American continent.

A chronicler of his time, the vision of a united Latin America was reflected in his works, going back to titles like The Next Days (1963), the Vagamundo (Vagaworld) (1973) stories, The Book of Embraces (1989) and Paws Up: The Story of the World Upside Down (1989).

In 1985, he returned to Montevideo when Julio María Saguinetti assumed the country’s presidency by means of democratic elections. Together with Mario Benedetti and Hugo Alfaro, among others, he founded the weekly Brecha(Opening, or Breach). And then his own publication, El Canchito (a termof endearment referring to a little pig). He also joined the National Pro-Referendum Commission (between 1987-1989), which was formed to revoke the Law for the Expiry of State Punitive Presumption, to impede judgment of crimes committed during the military dictatorship in his country (1973-1985).

For his work, Galeano was honoured with the Casa de las Américas Prize in 1975 and 1978; the Uruguay Ministry of Culture Prize in 1982, 1984 and 1986; the American Book Award in 1989; the Stig Dagerman Prize in 2010; and the Alba Prize for Literature in 2013.

Upon receiving the Doctorate Honoris Causa from the University of Havana in 2001, the writer said, “I have loved this island in the only dignified way, with its lights and shadows,” while the jury definitively called the writer and journalist “a redeemer of the real and collective memory of South America and a chronicler of his time.”

In 2004, he wrote a “Letter to Sir Future,” which summarized his ambitions. “We are being left withouta world. The violent kick it like a ball. The sires of war play with it like a hand grenade; and the voracious squeeze and drain it like a lemon. At this rate, I’m afraid, sooner rather than later the world will be no more than a dead stone revolving in space, without earth, without water, without air, withouta soul,” he warned in this letter. “That’s what it’s about, Sir Future. I ask you, we ask you, not to put us out. To be, to exist, we need you to continue to be, we need you to continue to exist,” he wrote. “For you to help us defend our house, which is the house of time.”

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 310 new monthly donors in the next 4 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.