Truthout is a vital news source and a living history of political struggle. If you think our work is valuable, support us with a donation of any size.

DETROIT – On July 18, 2013, Kevyn Orr, the city emergency manager appointed by Republican Gov. Rick Snyder, declared Detroit bankrupt under Chapter 9 of the bankruptcy code. According to official accounts, Detroit is $18.5 billion in the hole, making this the largest of several recent bankruptcies declared by US cities and counties.

In theory, such a declaration means that all the city’s creditors will suffer and will have to accept only a fraction of what they’re owed. But when a bankruptcy judge decides who will have to make sacrifices, those making the most painful ones will be Detroit’s 21,000 retired city employees and its 9,000 current ones.

“Everything they’ve been promised, both contractually and kind of a social contract, is being pulled out from under them. It’s morally indefensible,” Michael Mulholland, vice president of Local 207 of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees told journalist Jane Slaughter. “I was told if I worked here I’d have a steady job and in my old age not be in poverty.” Mulholland’s pension as a retiree is $1,600 a month, not an income that can support a family, even in a city like Detroit, where housing prices have plunged.

The Detroit bankruptcy, while huge, is the latest of several that have had their sharpest impact on city workers. The city of Stockton, California, declared bankruptcy two years ago. In a court settlement this month, it forced its 1,100 retirees to accept a lump sum of $5.1 million to compensate them for canceling their previously guaranteed medical insurance. If each retiree gets an equal share amounting to $4,636, it would buy health insurance for only a year or two at current prices. In the US, there is no national health service, and people must buy insurance to pay the cost of medical care.

Huge US corporations have a long history of trying to shed obligations for pensions and health care for retired workers. In the most recent case, the Patriot Coal Company, created by mining giants Peabody Energy and Arch Coal, declared bankruptcy while corporate creators continued to amass large profits. Patriot is responsible for the pensions and health care for 23,000 retirees and dependents who previously worked for Peabody and Arch before the spin-off. The new company says it can’t sustain the payments for the benefits workers earned over years of labor in the mines.

While cities like Stockton and Vallejo in California have used bankruptcy law to accomplish this same end, legislators in Michigan have gone one large step farther. Michigan first passed Public Act 101 in 1988, when Democrats still controlled the legislature and governor’s office. It allowed temporary emergency control of cities but barred canceling the contracts or benefits of employees. Then Public Act 72 in 1990 allowed the appointment of emergency managers to take control of school systems.

Finally, in 2011, Republicans took control of the Legislature and governorship. They passed Public Law 4, which was much more radical and gave virtually unlimited powers to emergency managers appointed by the governor. Those managers could completely displace elected local city councils, mayors, school boards and other public bodies. Newly elected Gov. Snyder then ended collective bargaining rights and employee status for almost 26,000 child-care workers belonging to the United Auto Workers and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees.

Schools in Highland Park and Pontiac have had three emergency managers, and one manager in Highland Park has been indicted for embezzling. In Benton Harbor, the emergency manager sold off the sports arena built with $55 million of public funds to a developer for $583,000. He even barred the mayor from entering his own office. In Hamtramck, the financial manager stopped paying the mayor and City Council and told the council members to stop meeting. In Ecorse and Highland Park, financial managers made major layoffs to the fire and police departments, outsourcing many jobs to neighboring cities.

In Detroit’s schools, part of the agenda has been privatization. By the end of the 2009-10 school year, 50,139 students (36 percent) in Detroit already were attending charter schools. Robert Bobb was then brought in from Oakland, California, as emergency manager and unveiled a plan to covert an additional 41 schools (30 percent of the district) serving 16,000 students into charter schools. Bobb’s plan was linked to the Deficit Elimination Plan – an agreement he made with the state. It required the district to close 70 schools over two years and raise class sizes to 60 students at the high school level.

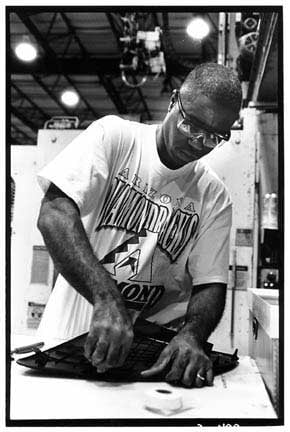

(Photo: David Bacon)Voters rebelled and repealed Public Law 4 in 2012. The legislature grew even more radical, however, passing a law forbidding contracts that require union membership as a condition of employment (a so-called “right to work” law) then passed Public Law 4 again in a slightly modified form, as Public Act 436.

(Photo: David Bacon)Voters rebelled and repealed Public Law 4 in 2012. The legislature grew even more radical, however, passing a law forbidding contracts that require union membership as a condition of employment (a so-called “right to work” law) then passed Public Law 4 again in a slightly modified form, as Public Act 436.

In March 2013, Snyder appointed Orr as Detroit’s emergency manager. And on July 18, Orr forced the city into bankruptcy. City unions charged that he was unwilling to negotiate with them about the move and that his assistants would simply show them PowerPoint presentations during meetings in which they were supposed to bargain.

Anticipating what was to come, lawyers representing public union pension funds went to court to enforce a provision of the Michigan Constitution. It says, according to Ingham County Circuit Court Judge Rosemarie Aquilina, that the governor can’t “diminish or impair pension benefits.” Hearing that the judge was about to make her ruling invalidating any pending bankruptcy, Snyder and Orr declared bankruptcy a few minutes before she acted. The judge condemned the move, because it gives all authority to a bankruptcy judge and removes review by the normal court system. “It’s cheating, sir, and it’s cheating good people who work,” the judge told Brian Devlin, assistant state attorney general. On July 23, however, the state Court of Appeals granted a motion by Attorney General Bill Schuette to stay Aquilina’s order to stop bankruptcy proceedings because they violate the state constitution.

Veteran Detroit Congressman John Conyers, one of the most progressive in the House of Representatives, said the judge’s ruling mandated congressional hearings to determine whether Snyder and Orr were misusing bankruptcy to slash pensions and medical insurance. The chairwoman of the Congressional Black Caucus, Marcia Fudge (D-Ohio), called for Detroit to be provided federal aid like cities recovering from natural disasters. “Some want to unfairly make city workers and their pensions the scapegoats, but they are not the problem,” she said.

In another lawsuit, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People made an even deeper challenge to the emergency manager law. In US District Court, it charged that the law discriminates against African-Americans. More than half of Michigan’s 1.4 million black residents live under rule by emergency managers – which effectively nullifies their right to vote. By contrast, only 1 percent of white residents live under managers.

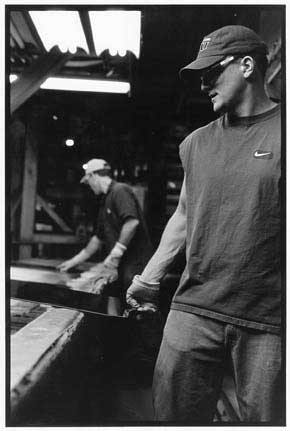

(Photo: David Bacon)That disparity is a result of Detroit’s history and its consequent financial crisis. The city shares a common history of the devastation of its industrial base with most of the largest US cities. To a greater or lesser degree, they all have suffered the same fate. If Detroit’s is deeper than most, it is in large part the result of its past as one of the most heavily industrialized places on the planet.

(Photo: David Bacon)That disparity is a result of Detroit’s history and its consequent financial crisis. The city shares a common history of the devastation of its industrial base with most of the largest US cities. To a greater or lesser degree, they all have suffered the same fate. If Detroit’s is deeper than most, it is in large part the result of its past as one of the most heavily industrialized places on the planet.

In the 1930s, the Ford River Rouge plant alone, in nearby Dearborn, employed more than 100,000 workers. Counting their families, direct employment at the plant supported perhaps half a million people. And for each assembly plant job, four or five more were created in parts plants, or in the businesses serving the needs of the workers. Those workers had families as well. One plant gave work and life to well over a million people, at least.

“The Rouge” was just the largest of many auto assembly factories in the metropolitan area. Detroit was a monoculture growing one crop – cars – and its workers were among the most skilled anywhere.

Detroit grew to be one of the country’s most African-American cities as well, at one time rivaling Washington, the Chocolate City, in the size and demographic weight of its black community. That also was a product of the auto industry, which together with the Midwest’s steel mills, drew people from the South in one of the largest internal migrations of modern times.

From 1940 to 1943, more than 200,000 migrant workers made their way to the city. Many blacks and whites from the South took with them the South’s racial attitudes and even racist organizations. Because that tension was used to set workers against each other and make the organizing of unions in the factories difficult, the union had to find ways to bring workers together. One was the celebrated “checkerboard marches” of the 1930s, where vast parades of workers were organized in such a way that black and white workers alternated in their ranks, walking beside each other in a show of racial solidarity.

Black workers, however, were given the dirtiest, lowest-status jobs. Rapid migration resulted in extreme housing shortages. That, plus rampant discrimination and segregation, led to tension between white and black residents. In June 1943, the tension exploded in the Detroit Race Riot, which lasted for three days before federal troops restored order.

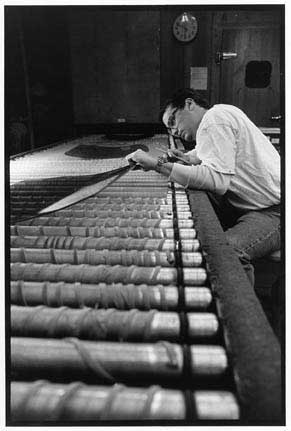

(Photo: David Bacon)By 1950, many union members believed in workplace integration but still lived and socialized in segregated neighborhoods. White residents worried that black newcomers would harm property values. Black families had to fight racial covenants, redlining and hostile neighbors. Many white residents fled to segregated suburbs in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties.

(Photo: David Bacon)By 1950, many union members believed in workplace integration but still lived and socialized in segregated neighborhoods. White residents worried that black newcomers would harm property values. Black families had to fight racial covenants, redlining and hostile neighbors. Many white residents fled to segregated suburbs in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties.

During the 1960s, racial tension grew. On July 23, 1967, a police raid on an after-hours bar triggered one of the biggest riots in American history. Conditions in inner-city plants were the worst in the industry. Black and white workers often felt neglected by union leadership. A new generation of militant black workers organized the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) and accused Chrysler of recruiting common labor from the black ghetto while going to white suburbs to recruit supervisors and skilled workers. Its efforts collapsed in 1971, but the turmoil it created forced companies to hire more black foremen and the UAW to hire more black staff members. Many local unions elected black presidents.

Migration took place also from Mexico and the Middle East. The first wave of Mexicans went into the plants in the 1920s. They were then caught in mass deportations that shipped them back across the border in 1930, often in railroad cars. Yet thousands returned to Detroit as soon as they could. Some families, like that of Elena Herrada, came back as early as 1932. When they returned, she said, some families realized that their children actually were American citizens – babies who had been born before their parents were deported.

Then another wave came with the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1993 – part of a migration that totaled more than 8 million people over the next 15 years. “There wasn’t anybody new here for a long time, until NAFTA,” Herrada told journalist Julie Bally.

People came from the Middle East as well: first, a wave of Chaldeans (from what later became Iraq) and Palestinians before World War I. Then Yemenis came right afterward, with another wave from Lebanon and Syria. Today people from the Middle East number over 300,000 in Detroit and perhaps half a million in Michigan.

(Photo: David Bacon)“Everywhere in the country and in the world, people left their beloved homelands to try their luck in this cold, faraway place where all you had to do was be willing to work,” Herrada wrote in 2009. She is a member of the Detroit School Board and one of the most vocal opponents of the bankruptcy. “Whether one came from the segregated South, post-revolutionary Mexico, Europe, Kentucky or the Virginia mines, everyone who came here was ready to work. And there was plenty of work to go around.”

(Photo: David Bacon)“Everywhere in the country and in the world, people left their beloved homelands to try their luck in this cold, faraway place where all you had to do was be willing to work,” Herrada wrote in 2009. She is a member of the Detroit School Board and one of the most vocal opponents of the bankruptcy. “Whether one came from the segregated South, post-revolutionary Mexico, Europe, Kentucky or the Virginia mines, everyone who came here was ready to work. And there was plenty of work to go around.”

They were the base of the United Auto Workers and helped create a union culture with deep roots. “We grew up walking every picket line in town, whether my parents worked there or not,” she remembers. “We took food to strikers, talked Union at the dinner table, and to hear my family tell it, the working class would save the human race.”

Active UAW membership peaked in the 1970s at 1.5 million, falling to 540,000 in 2006. After the restructuring of the automobile industry from 2008 and 2010, UAW membership fell to 390,000, with more than 600,000 retired members.

Today most of Detroit’s auto plants are closed. Jobs that paid a wage that allowed parents to send their children to college disappeared as auto manufacturers moved production to countries with wages that don’t allow such “luxuries.”

“All that is gone now,” Herrada mourned. “No longer is longevity rewarded; older workers are run out, replaced by employees who must work for less. Two-tier contracts are the rule now, not the exception. Older workers in high-wage industries under collective bargaining agreements are an endangered species. They will not reproduce. They are nearly extinct.”

And today a greater percentage of African-Americans are part of the population of Mississippi (in the heart of the deep South) than any other state, as the great migration reverses itself and people leave Detroit and other cities in the north to go back to the land where their ancestors were owned as slaves 150 years ago.

By the 1950 census, Detroit’s population had reached its highest point – 1,849,568 people living within the city limits, with many more in Flint, Dearborn and the other satellite auto towns around it. The Southeast Michigan Council of Governments estimates Detroit’s population today at much less than half – 772,419 – and says it has lost 2,000 residents each month since downsizing began in the 1960s.

(Photo: David Bacon)Just from 2000 to 2010, Detroit lost one-quarter of its population; 273,500 people. After New Orleans, which lost 29 percent of its population in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Detroit’s 25 percent loss is the largest percentage drop in the history of an American city with more than 100,000 people. Ten years ago, Detroit was the tenth-largest city in the country. Demographers at the Brookings Institute now believe it might be the 18th. That’s the smallest it’s been since 1910, just before the automotive boom brought millions of well-paid jobs and turned Detroit into the Motor City.

(Photo: David Bacon)Just from 2000 to 2010, Detroit lost one-quarter of its population; 273,500 people. After New Orleans, which lost 29 percent of its population in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Detroit’s 25 percent loss is the largest percentage drop in the history of an American city with more than 100,000 people. Ten years ago, Detroit was the tenth-largest city in the country. Demographers at the Brookings Institute now believe it might be the 18th. That’s the smallest it’s been since 1910, just before the automotive boom brought millions of well-paid jobs and turned Detroit into the Motor City.

In 1960, Detroit had the country’s highest per-capita income. Today, while Detroit makes up only 23 percent of the metropolitan region’s population, it is home to nearly half of the people living in poverty. Median household income for Detroit residents ($26,098) is less than half that of residents in the suburbs ($54,688), and 52 percent of that of US residents generally ($50,221).

Another consequence of the crisis was the concentration of African-Americans, Mexican-Americans and Arab-Americans in Detroit’s urban core, while more affluent white people left for the suburban areas that surround it. Half of Michigan’s black population now lives in the city of Detroit. In the suburbs, only 9.6 percent of residents are black.

In October 2009, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found the city’s unemployment rate was 27 percent. Detroit Mayor Dave Bing, however, argued that this number was an undercount, because it doesn’t include people who have given up looking for work or those working part-time jobs because they can’t find full time ones. He said that one of every two working-age Detroit residents was unemployed or couldn’t find enough work to support themselves. In any city with high unemployment and precarious jobs for those working, an economic downturn wreaks much more havoc than it would in a more stable community. The Detroit News estimated that when the current recession began, Detroit’s official unemployment rate jumped 7.2 percent in one year.

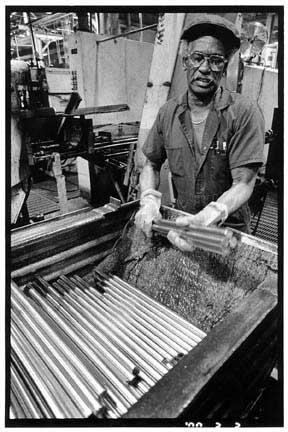

(Photo: David Bacon)High rates of unemployment, in turn, produce widespread poverty. Michigan, even counting communities far from Detroit that aren’t as affected by the decline of the auto industry, has one of the highest poverty rates in the country. Detroit ranks last in median family income, per capita income and the number of families and individuals living below the poverty line. During the past decade, median household income dropped by 31 percent, and the region around the city by 24 percent.

(Photo: David Bacon)High rates of unemployment, in turn, produce widespread poverty. Michigan, even counting communities far from Detroit that aren’t as affected by the decline of the auto industry, has one of the highest poverty rates in the country. Detroit ranks last in median family income, per capita income and the number of families and individuals living below the poverty line. During the past decade, median household income dropped by 31 percent, and the region around the city by 24 percent.

To a large degree, the public sector became the major employer in the absence of industry. More than a quarter of the city’s workers are employed in health, education and social assistance, more than twice the number in any other cluster of occupations. Those jobs, however, are heavily dependent on the tax base and vulnerable to economic downturns that erode tax revenues. A lower percentage of people work in management and professional positions than any other city in the Great Lakes region.

The declining tax base eroded the ability of the city to supply basic services, and it can no longer maintain and manage its public works, its water system, its buses or its parks. Detroit Public Schools lost half its students in the past decade, a rate even faster than the loss of population generally. Only 65 percent to 70 percent of high school seniors make it to graduation, according to the Detroit Literacy Coalition.

The DLC has trained more than 200 tutors at the Detroit Public Library to help people learn to read. Dreams of better jobs, however, have to contend with the deterioration of the city in which students have grown up. Detroit occupies 138.7 square miles of land, with 375,000 homes. While there are plenty of apartments, the city was one of the places where the postwar dream of the single-family home was realized by large numbers of working-class families. Today 66,000 properties are vacant, with 78,000 in foreclosure, amounting to 30 percent of the city.

So many homes lie vacant that proposals have been made for 20 years that the city wall off “dead zones,” moving out the residents and demolishing their homes, and supplying city services only in the remaining populated areas.

Meanwhile, Orr has announced that he plans to sell major Detroit assets, including Belle Isle Park, the largest public park island in the country, and the huge Water and Sewage Department, as well as cutting almost half the city’s street lighting. Rumors in the city say its world-famous art museum, with murals by Diego Rivera and paintings by Picasso, also is up for sale.

(Photo: David Bacon)In addition to challenging these plans in court, protest demonstrations and civil disobedience are spreading. Four community leaders were arrested as hundreds of others disrupted an April City Council meeting, charging that they were turning over control of city finances to a law firm tied to the banks holding the city’s loans. One of those arrested was Herrada, a former union organizer among cafeteria workers. “We should oppose the emergency manager at every turn,” she said at a meeting of the Detroit library commission. “We have no one but ourselves to depend on and our own resources to fight with.”

(Photo: David Bacon)In addition to challenging these plans in court, protest demonstrations and civil disobedience are spreading. Four community leaders were arrested as hundreds of others disrupted an April City Council meeting, charging that they were turning over control of city finances to a law firm tied to the banks holding the city’s loans. One of those arrested was Herrada, a former union organizer among cafeteria workers. “We should oppose the emergency manager at every turn,” she said at a meeting of the Detroit library commission. “We have no one but ourselves to depend on and our own resources to fight with.”

On July 4, 2013, a long line of marchers showed up at the swank Cadillac Hotel, where Orr has been living since arriving in Detroit. The marchers demanded independence from city managers. One of them, Elder Helen Moore of the Keep the Vote No Takeover Coalition, founded in 1999 to combat the takeover of Detroit Public Schools, said, “There is no reason to celebrate the Fourth of July, because Detroit is not free. We have no democracy. Our school system has been practically destroyed by state takeovers. We are crying out today for freedom for our people, black, white and Latino. We don’t do second-class citizenship very well.”

“When you hear that the service is terrible in Detroit,” Herrada laughed in a telephone conversation with Truthout, “imagine us raising our collective glass in cheer, because we did not come here to serve anyone.”

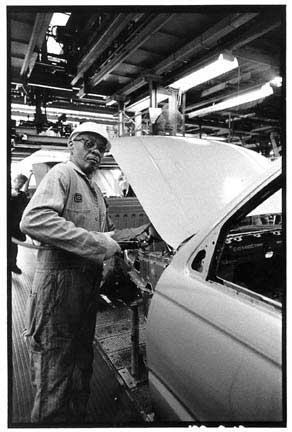

The photos accompanying this article were taken by David Bacon in auto plants in Detroit and around the country. They are reproduced here to acknowledge the importance of their work in building Detroit and other cities, and the physical and mental effort expended by millions of people in these factories. These workers created the enormous wealth of this industry, yet the communities where they labored are often now in ruins because the plants have closed, the jobs taken elsewhere.

Copyright David Bacon.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 500 new monthly donors in the next 9 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.