I work with, lead education events with, and talk with White anti-racists all over the country, and over and over again, questions of how to do this work, concern for doing it right, fears of mistake, are often the focus of what we talk about. My goal over and over again is to help move people through the demobilizing effect of endless questioning and concern, and the underlying fear, so that white anti-racists can step up with courage, vision, strategy and love, to engage and move White people, in large numbers, toward anti-racist consciousness and action.

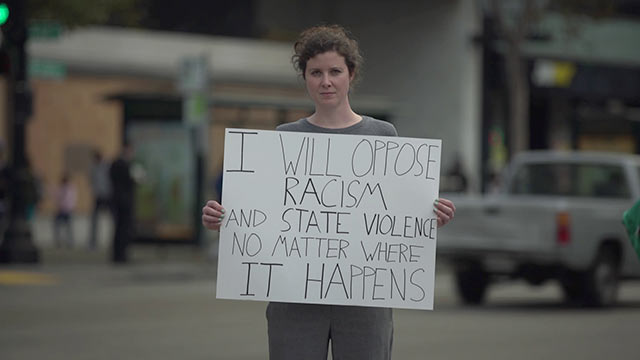

We are living in a time in which millions of White people are having their hearts, minds and souls shaken, devastated and opened by the national debate and coverage of racist police violence and by the militant protests and uprisings of the Black community.The Black Lives Matter movement has changed the political landscape of the country toward racial justice with Black liberation vision, strategy, culture, resilience and resistance at the forefront, with a new generation of Black leadership rising to meet the challenges of our time.

Around the country there are also White racial justice organizers and leaders who, even though they have questions, concerns and fears, are also cultivating dynamic and healthy approaches to throw down against White supremacy and work for the structural and cultural changes that Black Lives Matter demands. Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) is one of the organizations both nationally and locally that has been at the forefront of cultivating this fearless, love-based, possibility-focused approach to organizing. And it is both facilitating and coming from a massively growing membership, new chapters, a continued use of direct action and civil disobedience and a compelling justice vision that is resonating with more and more people.

The Jewish community is multiracial, and Jews as a group, along with many other groups (Irish, Eastern Europeans, Germans) were racialized into White supremacy and Whiteness in the late 1800s as part of the Americanization programs to divest them from multiracial working-class solidarity for a better world and invest them into the ruling-class logic and structures of White supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

That said, this interview is focused on organizing in majority white Jewish communities for racial justice and Black Lives Matter. It is also a collective interview with JVP leaders Rebecca Vilkomerson, Stefanie Fox, Rabbi Alissa Wise, Cecilie Surasky and Ari Wohlfeiler.

My goal with this interview series is to help equip white people to be courageous, humble, visionary, accountable, loving and effective as we, as White people, work to save White communities from the death culture of White supremacy and unite our people with the deeply life-affirming, liberatory power of the Black Lives Matter movement. While White people need to be mindful of how White privilege operates, we must also be powerful for collective liberation, knowing that the time for us to rise against structural racism is now. Let us build, together.

Chris Crass: How are you working to move White people into racial justice movement in this time? What’s working? And what are you learning from what works?

Jewish Voice for Peace: Jewish Voice for Peace is a national organization working for equality, justice and freedom for all people of Palestine and Israel. As such, we see our work as having always been part of a racial justice movement.

Over more than 10 years, our understanding of our role in moving White people into racial justice movement has evolved through experimentation in words and deed. Vigils, discussion groups, leadership retreats, emergency mobilizations, divestment campaigns, late-night conversations, spiritual practice and cultural events have provided opportunities for our members to think through an understanding of how our work is based in racial justice and how what we do impacts other struggles.

Fairly early on in our journeys, each of us is confronted by the myriad ways our voices as Jews are privileged as more valid than the voices of Palestinians. This experience quickly brings many in the movement into a deeply personal and immediate confrontation with our own positionality and privilege, whether as White people or as Jews. Naming it, and taking intentional actions to mitigate its impact, are just the first steps in a longer process of understanding our work as racial justice work.

We pay attention to the small details of organizing and leadership development on a daily basis – how are group dynamics, how do decisions get made, what relationships should we build with other organizations, how do we think about our positionality as Jews, who is good at talking to the press.

Last summer during the latest Israeli assault on Gaza, and later this fall as #BlackLivesMatter activists took to the streets nationwide, our members led JVP into action in cities across the country. To both national and local leaders, the need to act was both obvious and urgent. In St Louis, New York and Baltimore, our chapter leaders had been doing their JVP organizing in coalition for many years and already had active partnerships with African-American-led organizations, and so felt a sense of local accountability even more than a national mandate from JVP. We were grateful and eager to be led in this way, from our relationships in the grassroots on up.

Building on this strength, in other cities, and for our membership at large, we offered resources and opportunities for engagement that encouraged our people to act and offered a political framework for those actions. In turn, JVP’s participation in actions alongside, and often led by, Palestinian and Black organizers deepened the relationships and experience we can now draw on to further strengthen our work.

Marching against Israel’s attack on Gaza, summer 2014, Boston, Massachusetts. (Photo: Marilyn Humphries)

Marching against Israel’s attack on Gaza, summer 2014, Boston, Massachusetts. (Photo: Marilyn Humphries)

How do you think about effectiveness, and how do you measure it? Can you share an experience that helps you think about effective work in White communities for racial justice?

We have built a dramatically larger and stronger organization, and the assumptions of public debate about Israeli policies toward Palestine – and of the legitimacy of Israeli democracy itself – have moved, for the better. That said, none of our accomplishments has perceptibly reduced the daily and structural violence Palestinians face.

It’s thus impossible for us to talk about effectiveness without needing to name and hold this tension that during the horrific war on Gaza this summer, so much of our growth, as an organization and as a movement, occurred. Our chapters were forged and strengthened by doing civil disobedience together, and literally dozens of new chapters formed. Across the US and around the world, tens of thousands of people poured into the streets and committed themselves to this struggle.

Our work is not to convince people of our knowledge, but to give people room to respond to the fire of their own truth.

So we are both facing enormous solemnity and urgency and obligation to do the work we need to do to make real change, and we can also celebrate the hope that comes from feeling, really feeling, how much this movement is growing and how much more growth we are still poised to bring. So it’s all true and all part of how we think about effectiveness: the urgency and the hope; the mourning and the determinatio;, the spark of transformation; and the building of community.

Another aspect of effectiveness for us is measured in very deliberate and focused training around the brass tacks of organizing. We pay attention to the small details of organizing and leadership development on a daily basis – how are group dynamics, how do decisions get made, what relationships should we build with other organizations, how do we think about our positionality as Jews, who is good at talking to the press – so that when crises arrive, we can trust ourselves and each other to show up correctly. We saw this all summer and into the fall as our chapters transformed years of training and practice into our most powerful actions ever to protest Israel’s horrifying assault on Palestinians in Gaza and to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Chanukah 2015 video still, Oakland, California. (Photo: Zach Behar)

Chanukah 2015 video still, Oakland, California. (Photo: Zach Behar)

What are the goals and strategies (as emergent, planned, messy and sophisticated, basic as it is) you’re operating from?

We’ve got to grow. One of our big, messy, beautiful goals is to grow fearlessly – in terms of absolute numbers, and in terms of the commitment, power and savvy of our members. We believe we can only do that by practicing a really expansive kind of compassion and at the same time a serious kind of rigor: remembering we’re all somewhere we weren’t before, we’re all still learning, and at the same time giving none of us permission to stop learning, pushing, growing. It’s in this way that we feel we will build a movement huge enough and resilient enough to make real change. Though we are typically thinking about this goal in relationship to bringing Jews into the movement for justice in Palestine, it certainly also applies to the way we are operating when we think about organizing the White Jews in (and more importantly, beyond) our organization. We don’t get to just build with the folks that make us feel best about our perfect analysis, but instead, we have an obligation to reach out to people who are still struggling to understand their own complicity in anti-Black racism and to learn with and from each other as we spring into action.

Our work is not to convince people of our knowledge, but to give people room to respond to the fire of their own truth. There is a brutal reality that the greatest periods of growth and mobilization in our movement have consistently come during and from Israeli military assaults. Like economic crashes and police brutality, these assaults and invasions are guaranteed by the political economic system itself, but the death, destruction and terror of Israel’s military assaults do not follow a set schedule. Knowing that, one of our most important goals is to be there for people when reality becomes unavoidable. Septima Clark said: “I believe unconditionally in the ability of people to respond when they are told the truth.” In moments of great tragedy we see openings where people allow themselves to be told the truth. It is our work to give them the space to respond.

Speak from the heart. Knowing the myriad ways people come to the movement, and the ease with which groups can devolve into incapacitating ideological arguments, early on we explicitly developed a values-based approach to language we use with mass communications channels. To quote Edward Said, “equality or nothing.” Our growth is itself a strong measure of our effectiveness, and of the power of that language. Clearly, focusing on equality does not automatically assume a deep understanding of race, but it does provide a strong foundation for building a deeper analysis for those who move along with us – especially given how hard it is to argue that Israeli policies meet even the most basic tests of equality.

Maintain solidarities and accountabilities. At our recent National Membership Meeting, Angela Y Davis said to us, “It is necessary that JVP lead. And it is necessary that JVP take leadership from People of Color.” This is our dual mandate. We act in solidarity, and without taking leadership from Palestinians our work would be meaningless. At the same time, we also have to be the most effective we can possibly be in moving our own people – in moving Jews, and for those of us who are White, moving White people. As Jews doing work for Palestinian liberation and for ways of being Jewish that do not condone or allow racial violence, we are always spending a lot of time thinking about the dynamics of power, positionality, privilege and voice.

Make connections. Another goal we strive for is to make our campaigns intersectional in demand, tactics and relationship. Sometimes that means looking for targets that live in the intersections of our struggles – that follow the systems of control, violence, domination and profit – from Ferguson to Ramallah. But just as important as the connections between the “bad actors” in our work, so too we want our campaigns to make connections between the love in one liberation struggle and the next. We look for opportunities for a kind of passion, love, spirit or ruach, whatever you want to call it, to catch from one movement to the next. Sometimes just turning out for each other’s actions and swapping stories and strategies and lessons learned from one action or campaign to the next is an even more vital point of connection than finding a common target or demand.

What challenges are you facing? How are you trying to overcome them? What are you learning from these experiences?

One of the biggest challenges we face in trying to draw the (for us) obvious connections between liberation movements in the US and Palestine/Israel [despite] the deeply ingrained notion in the Jewish community that such connections are distracting, off-topic, or ill-intended. The idea in institutional Jewish communities that you can be progressive except for on Palestine is not only allowed, but actively cultivated, and reinforced by funding streams that demand self-censorship, specifically to prevent racial-justice frameworks developed and used by Jewish organizing in a US context from being applied to Palestine. But in JVP, we don’t see the world that way, and indeed most of us come to JVP desperate to find a political home where we can bring our full Jewish, activist selves, along with our holistic understandings of the world, including global systems of oppression. So attempting to join or help lead broad Jewish mobilizations as part of the Black Lives Matter movement has been challenging.

Conversely, too many of us – White and of color, working on US and Palestine-based struggles – settle for simplified connections between our struggles. It’s a problem that G4S runs privatized prisons in Israel and the US, or that US and Israeli police forces train each other. Those are legitimate and worthy campaign targets. And we also want to encourage people to look deeper. Whether or not your local police chief goes to Israel, what is it about policing as a system itself that links our struggles? And even if G4S is a fabulous coalition-building target, how do we fight a private prison company without obscuring the fact that 95 percent of prisoners in the US are in public prisons? We believe asking these questions is critical to devising strong campaigns and also that the conversations themselves offer opportunities to join in the debates and dialogues that will form the basis of future emergency-response networks, coalitions and alliances.

We also have a lot to reckon with in terms of racism and systems of exclusion within our organization and within the Jewish communities we are a part of. Heeding the call of the Black Lives Matter movement is for us a chance to reclaim and extend those moments and movements in long and varied Jewish histories, where Jewish people fought for justice and liberation – for themselves and others. And at the same time it is about taking off the rose-colored glasses on Jewish history that sometimes lead us too quickly to the photograph of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heshel marching alongside Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, rather than to grappling with the history of Jews who were slaveowners or Jews who were part of White flight in the ’70s and part of rampant gentrication and displacement in urban centers today. A challenge of our work is to face and carry both, to see our inspiration and obligation in the proudest and ugliest parts of our histories.

Whether or not your local police chief goes to Israel, what is it about policing as a system itself that links our struggles?

Furthermore, we have a lot to take up within our own organizational history, patterns and practices. We are an organization predominantly of White Ashkenazi Jews that has until very recently not systematically addressed the experiences of Mizrachi and Sephardi Jews, or of Jews of Color in JVP. Mizrachi, Sephardi and other Jews of Color within JVP have just started to organize to connect with each other and critically examine the workings of race and racism within our own organization, in what we expect will be the beginning of an ongoing process.

We have an ethic as organizers to make the road by walking.

From this follows the challenge to speak directly and powerfully to White people within the organization and the levers of power so many of us have access to as White people without alienating members of color or flattening the multiracial reality of JVP and Jewish opposition to Israeli policies. We often speak of our power as coming from the “J in JVP” – but the work ahead of us includes more intentionally sketching the Venn diagram of White and/or Jewish opposition to occupation, dispossession and institutionalized discrimination.

How are you developing your own leadership and the leadership of people around you to step up in these profound, painful and powerful Black Lives Matter movement times?

We have an ethic as organizers to make the road by walking. The Black Lives Matter uprising provides a powerful new path for us to move along, all the while seeking to refine our thinking and our work. Rather than trying to get it perfect, we believe it’s our obligation to jump into action when called. We encourage members to take leadership, try things out, jump into the fray. And then to have an intentional, iterative process and an openness to feedback to help us internalize the lessons as we keep moving ahead.

As organizational leaders, we think stepping into leadership in this moment is largely about taking hard questions that emerge from our base and our allies, and translating those questions into priorities for inquiry, policy and practices. For instance, as Jews of Color in JVP are beginning to connect with each other around their own experiences in our organization, it’s critical that we find ways to put resources – money, staff time, priority within the long list of organizational conversations – into those connections immediately. And to do so knowing that an immediate political investment is prelude to hopefully even deeper commitment.

As for so many others, the Black Lives Matter movement is a source of inspiration, hope and challenge for us as individuals and as an organization. We don’t know many of the answers yet, but we do know that we have a deeply held commitment to continuing to integrate the action we are taking, lessons we are learning, relationships we are building and the analysis we are developing into all aspects of our work.

Leaders from JVP who worked on this interview:

Stefanie Fox is the co-director of Organizing at JVP and has been on staff since 2010. She brings over a decade of field organizing experience, a masters in Public Health focused on community organizing, and deep love for the beautiful, messy, exhilarating sometimes-slog of grassroots movement building.

Rebecca Vilkomerson has been executive director of JVP since 2009 and a member since 2001. In previous lives she has organized around welfare rights, ending homelessness and immigrant rights.

Rabbi Alissa Wise is JVP’s co-director of Organizing at Jewish Voice for Peace and has been an activist for justice in Israel/Palestine for over a decade. She is founding cochair of the JVP Rabbinical Council and the Nakba Education Project (NEP), which offers educational resources to an American audience about the history of the Nakba and its implications in Palestine/Israel today.

Cecilie Surasky is JVP’s deputy director and one of the founding members. Her analyses have appeared in numerous print outlets including The New York Times, Boston Globe, The San Francisco Chronicle, the Nation, Ha’aretz, the Jerusalem Post, and more.

Ari Wohlfeiler is from Oakland, California. Before coming to JVP, he was the development director at Critical Resistance and has worked with Californians United for a Responsible Budget and grassroots organizations fighting the prison industrial complex.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.