As the eviction moratorium sputters uncertainly onward, a new genre of news article has emerged from the chaos: the woes of the so-called “mom-and-pop landlord.” These landlords — individuals with just a handful of rental properties — are hard-pressed to keep up mortgages and maintenance due to their inability to collect rent during the COVID crisis. Most landlords featured in such stories agree that ending the moratorium is the answer.

“What’s the difference between me and a grocery store or a restaurant?” Carol Kelly asked The Washington Post. “You would never go into a restaurant and say, ‘Please feed me for the next 12 months and I’ll give an IOU.’” Michelle Quinn, a partner at a law firm, agreed. “Really the landlords are the party taking the brunt of the effect of the pandemic…. They’re giving tenants a break, but not giving landlords a break,” she told Forbes.

Some claims verge on self-aggrandizement. “Next to the front-line medical workers and emergency responders, I think the small-business landlords who have kept their tenants housed should be getting a good deal of credit,” Jerry Howard, CEO of the National Association of Home Builders, told Politico.

Others point to emotional distress as reason to overturn the moratorium. “The stress and anxiety, the mental stuff,” Vanie Mangal told The New York Times in one of the most high-profile articles on afflicted landlords, “It’s too much.” The Times article described a nightmare scenario: destructive and noisy tenants who refuse to pay rent or negotiate. The article neglected to mention what internet sleuths quickly figured out: The units in question are illegal and have been the subject of neighbor complaints, including unaddressed flooding issues.

As Mangal’s situation suggests, the plight of the small landlord is complicated. It is true that the so-called mom-and-pop landlords are feeling the squeeze, though not to the extent they like to pretend. At worst, these beleaguered landlords will lose their rental properties, while those they evict stand to lose housing, a financially stable future and even their lives as the Delta variant surges. Yet landlord complaints are not entirely unfounded. As mom and pops begin to exit the rental market, large corporate entities are already swooping in to buy up the excess stock, which threatens to funnel wealth into the pockets of the ultra-rich, put further pressure on remaining small landlords to sell and create worse conditions for tenants down the road

Who Owns Rental Property?

The term “mom-and-pop landlord” has no official definition and does little to convey the actual spectrum of landlords within the rental market. Housing reports instead tend to divide the rental landscape into individuals and business entities.

According to the Brookings Institute, business entities control just over 60 percent of rental housing, and own an average of 20 units each. The rest of the U.S.’s rental stock belongs to unincorporated individuals. Most of these small landlords do well financially — 70 percent of individual landlords make over $90,000 per year, well over the national median income of $79,900.

There are, however, some small landlords who may be in a very precarious position as a result of the eviction moratoriums. The small minority of these landlords making less than $50,000 per year depend on rent for 20 percent of their total income, which means a lack of rent can constitute a genuine hardship. This burden falls especially heavily on senior citizens who depend on rental income for their retirement; according to the Urban Institute, 34 percent of property owners of two- to four-unit buildings are over the age of 65. Of these, 81 percent have no other job and 40 percent still owe mortgage payments on their rental properties.

Is it true that only the elimination of eviction moratoria can help these landlords? Under analysis, most of their arguments in favor of resuming evictions fall apart.

Disproportionate Harm?

Greta Arceneaux, like many landlords, feels abandoned by the government. “I don’t understand how they can come up with all of this financial aid for the homeless, for renters, for agriculture, for big business, for airplanes,” she told Time Magazine. “And they’re forgetting about the small mom-and-pop people that have two units or four units.”

Arceneaux may not be aware of it, but the American Rescue Plan (ARP) passed in March 2021 has instituted two programs that can help small landlords. While only businesses with a payroll were able to take advantage of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, the Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) program offers businesses adversely affected by the pandemic — including small landlords — loans of up to $500,000. The ARP also set aside nearly $10 billion in relief specifically for landlords making less than 150 percent of median income in their area.

Even without considering these programs, it is disingenuous to focus on the plight of small landlords without looking at the comparatively larger harm of eviction. Evictions mean more than the loss of housing. Evicted tenants can often only find housing in far worse neighborhoods, which exposes them to poorer education for their children, physical and mental health troubles, and deepening financial insecurity.

“It doesn’t really hold water to me to say that landlords are uniquely hurting relative to their tenants during the pandemic,” says Max Besbris, assistant professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Besbris points out that evictions disproportionately impact Black women and other women of color, which can lead to increasing inequality in the long-term. A 2019 study found that homeowners have an average net worth of $255,000, while the average tenant has a net worth of $6,200. Landlords, who own more than one home, are far more comfortable than the tenants they wish to evict.

Unlike their tenants, mom-and-pop landlords also have backup from powerful organizations that work to protect their interests. In Maryland, for example, many small landlords belong to the Maryland Multi-Housing Association, an organization dedicated to lobbying both state and national government for landlord-friendly legislation.

Evictions and the Delta Variant

In a June CNBC article, the CEO of the Small Multifamily Owners Association indulged in a bit of hyperbole. “The eviction moratorium is killing small landlords, not the pandemic,” asserted Dean Hunter, who is a landlord himself. This callous statement, printed two months ago in the wake of over 600,000 dead of COVID-19 in the U.S., seems positively ghoulish in light of the surge in COVID cases due to the Delta variant.

Multiple studies of the effects of eviction moratoria demonstrate that prohibitions on evictions save lives. A study published in the Journal of Urban Health in January 2021 found that evictions lead to overcrowding, houselessness, decreased access to health care, and an inability to adhere to CDC recommendations such as social distancing, all of which increase COVID transmission. An April 2021 study reinforced these conclusions when scientists used established epidemiological modeling techniques to simulate the transmission of COVID with and without strict eviction prevention. In every simulation, evictions led to more infections — not merely among those evicted but across entire urban areas. These findings became more dramatic when applied to poorer neighborhoods.

These predictions hold tragically true in practice. A July study, published in the American Journal of Epidemiology, studied 44 states with eviction moratoria between March 13 and September 30, 2020. Some of these states allowed their moratoria to lapse, while others kept eviction protections in place. Controlling for other variables, the study found that, 16 weeks after lifting moratoria, states experienced twice as many COVID infections and five times as many deaths as states that left moratoria in place.

“As the Delta variant spreads faster than the virus that was circulating last summer, we need to think about how these more transmissible variants of the virus might affect what we see when moratoriums lapse,” said Kathryn Leifheit, an epidemiologist at UCLA and one of the authors of the study. “The research that we did demonstrates that preventing evictions … are a really critical tool to help people stay safe and avoid infections.”

Wall Street Landlords

While allowing evictions to resume would be devastating for tenants by nearly any metric, moratoria without efficient rent relief come with long-term hazards as well.

According to a study by the National Rental Home Council (NHRC), 12 percent of single-housing landlords have already sold their properties as a result of their inability to collect rent, with more sales likely to follow.

“A lot of people who are small-time landlords are going to sell these properties that have become liabilities as a result of the pandemic,” Besbris said. “They’re going to sell them to much bigger corporations … what we call institutional landlords, who own hundreds if not thousands of properties.”

Institutional landlords are large corporate entities, such as private equity firms or real estate investment trusts (REITs), which allow investors to buy and sell shares in a large holding of rental property owned and managed by the fund. The nine largest REITs own nearly 250,000 single-family homes.

This “financialization” of housing means that trading of shares generates more revenue than the housing itself. Such practices ensure that money from rental property flows to shareholders rather than remaining in the community. Financialization can also cause disastrous bubbles and instability, as when the financialization of mortgages led to the 2008 recession.

Ironically, the housing bust of 2008 led directly to the financialization of single-family rental properties. In 2012, the Federal Housing Financial Agency launched a pilot program that allowed investors to buy foreclosed houses in bulk under the condition that they rent the houses for several years. The program, meant to stabilize the housing market, led to massive investments by REITs in single-family houses.

REITs and other equity firms are already moving to buy the property small landlords sell, along with anything else they can get their hands on. According to a report by Redfin, corporate investors bought nearly 68,000 homes in the second quarter of 2021, shattering previous records. Such practices drive up prices and make it more difficult for regular people to become homeowners. Little wonder housing prices reached an all-time high in March 2021.

Not only does this practice divert yet more of America’s wealth into the pockets of the ultra-rich, corporate landlords may be significantly worse for tenants than smaller landlords. Though Besbris emphasizes that more research is needed before sociologists can draw definitive conclusions, “It does seem that institutional landlords are worse for tenants in a lot of ways.”

What research exists supports this conclusion. A study by the Atlanta Federal Reserve found that corporate landlords are 8 percent more likely to evict tenants than individuals. This willingness to evict may result from the practice of charging late fees and other hidden fees, which can make evictions not just cost-neutral, but even profitable. This finding comes from a report released by the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (AACE), Americans for Financial Reform, and Public Advocates. Rental contracts also offload responsibility for maintenance onto tenants, including for appliance breakdowns and sewer issues. These institutional investors especially target communities of color: in Fulton County, Georgia, for example, corporate landlords own over 75 percent of housing in Black neighborhoods, compared to just 33 percent in white neighborhoods. Researchers in California have observed similar trends.

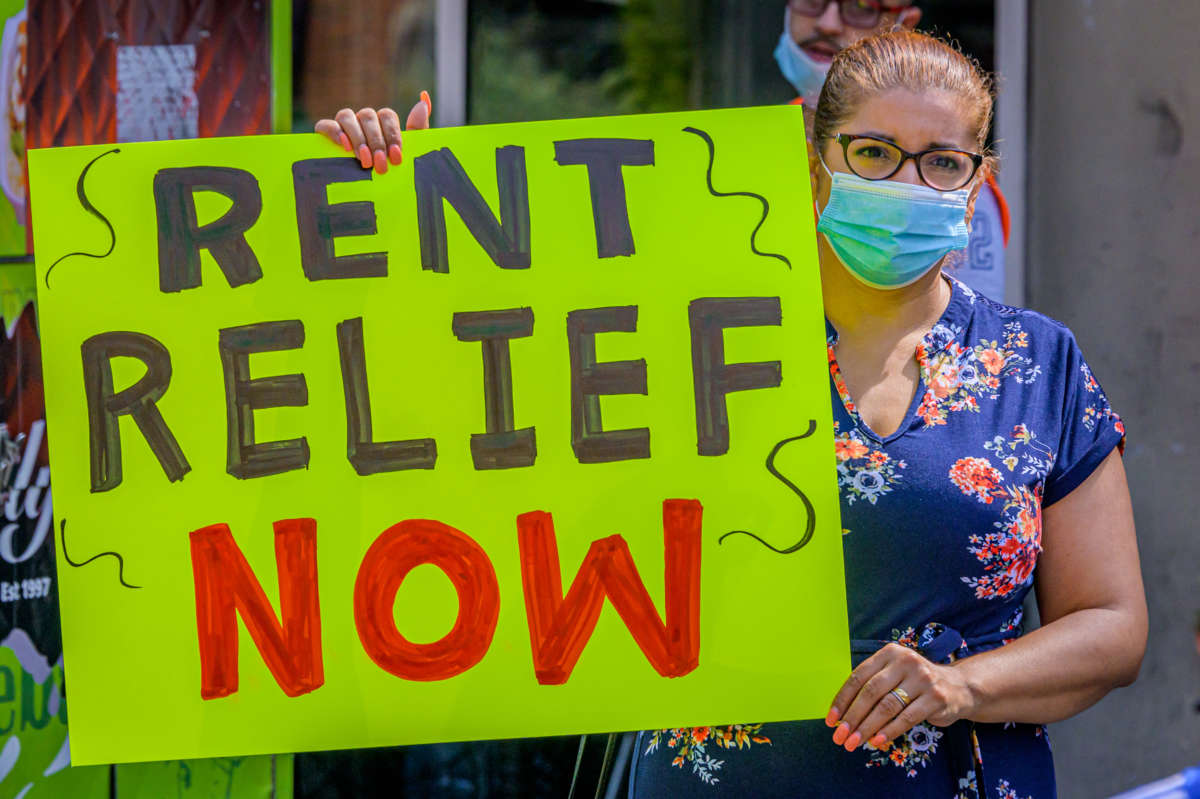

Rent Relief Now

The elimination of eviction moratoria would be devastating and even life-threatening. Yet the status quo threatens to give corporations even more power over everyday American life. What should be done?

“We could essentially have rent subsidies right now, instead of letting landlords evict their tenants, from whom they might still be owed a lot of money,” Besbris says. “We have the money for it. We just haven’t distributed it.”

The ARP of 2021 earmarked $46 billion for rental assistance. As of June 30, only $3 billion of this aid had been distributed. This money would both keep tenants in their homes and help save rental stock from the clutches of Wall Street financiers. Local government in Baltimore and Santa Fe provide models of how aid could be distributed more efficiently: both have worked closely with nonprofit organizations and activists to distribute aid more quickly.

“Rental assistance is now available in every state to cover up to a year-and-a-half of back and future bills,” says Patrick Newton of the National Association of Realtors. “We should direct our energy toward the swift implementation of this assistance.”

With multiple challenges to the eviction moratorium working their way through the court system, judges ignoring the moratorium entirely and assistance programs operating at a glacial pace, it remains to be seen whether the United States is capable of distributing rent relief swiftly enough to avert the humanitarian crisis of mass evictions looming on the horizon.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.