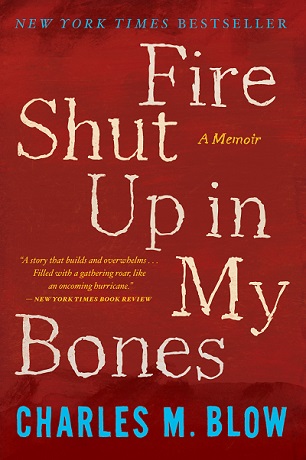

Charles Blow, 45, began his personal journey in rural and segregated Gibsland, Louisiana, growing up in “The House With No Steps.” He describes his first memories in the following excerpt:

The first memory I have in the world is of death and tears. That is how I would mark the beginning of my life: the way people mark the end of one.

My family had gathered at Papa Joe’s house because Mam’ Grace was slipping away, only I didn’t register it that way. For some reason I thought that it was her birthday.

Papa Joe was my great-grandfather. Mam’ Grace was his laid-up wife who passed the days in a hospital bed squeezed into their former den, looking out through a large picture window that faced the street, watching the world she was leaving literally pass her by.

We were in the living room when he called to us.

“I thank she ’bout to go.” I didn’t know what that meant. I thought it was time to give her a gift.

With that, my family filed into her room, surrounding her with love. Their hearts were heavy. Mine, though, was light. I thought we were about to give her something special. They knew something special was about to be taken away.

She peacefully drew her last breath as her head tilted, and she fell still.

No dramatic death rattle, no fear-tinged soliloquy, no last-minute confession. Like a raft pushed gently from the shore, she drifted quietly from now into forever – a beautiful life, beautifully surrendered.

But I recorded it differently. I thought she turned to see a gift that wasn’t there, and that something went tragically wrong in the turning.

When Mam’ Grace left the room she took the air with her. No one could breathe. They could only scream.

(Image: Mariner Books)My mother was overcome. She ran from the house, and I ran behind her. She threw herself to the ground near the hog pen, wailing, her back rocking against it. I shooed the hogs away as they tried to lap at her hair. I was too young to know what it meant to die, but tears I knew. Sorrow flooded out of my mother like a dam had broken. It was one, though, that she would soon rebuild, taller and stronger than it had been. As a child, I would never see her cry again.

(Image: Mariner Books)My mother was overcome. She ran from the house, and I ran behind her. She threw herself to the ground near the hog pen, wailing, her back rocking against it. I shooed the hogs away as they tried to lap at her hair. I was too young to know what it meant to die, but tears I knew. Sorrow flooded out of my mother like a dam had broken. It was one, though, that she would soon rebuild, taller and stronger than it had been. As a child, I would never see her cry again.

I spent most of my life believing my three-year-old’s version of what happened that day, until as an adult I recounted my memory to my mother and she set the story straight – our gathering at Mam’ Grace’s bedside was not to celebrate the day she was born but to accept that it was her day to die.

My mother’s telling of it seemed more fitting. As a child I became accustomed to death spectacles. I went to more funerals than birthday parties. My mother took me even when she left my older brothers behind. She thought me too young to stay home with them. I was also too young to understand what I was seeing at the funerals. My brothers once asked me how the dead man had looked at one of the services. I responded as a child would: “good, I guess. He was jus’ up there sleepin’ in a big ol’ suitcase.”

I was born in the summer of 1970, the last of five boys stretched over eight years. My parents were a struggling young couple who had been married one afternoon under a shade tree by a preacher without a church. No guests or fancy dress, just the two of them, lost in love, and the preacher taking a break from working on a house.

By the time I came along, my mother was a dutiful wife growing dead-ass tired of working on a dead-end marriage and a dead-end job. My father was a construction worker by trade, a pool shark by habit, and a serial philanderer by compulsion.

My mother was a stout woman with a man’s name – Billie. She was plain-faced with honest eyes – no black grease by the lash line, no blue powder on the lids, eyebrows not plucked up high and thin. She used only a stroke of lipstick, dark like a fig, and a little powder to cover the acne that still popped up under the balls of the cheeks that sat high on her face.

My father was short for a man, with a child’s plaything for a name – Spinner. He had flawless dark brown skin and a head full of big, wet-looking curls, black as oil. And he had the smile of a scoundrel – the kind of smile that disarmed men and undressed women.

We lived in the rural north Louisiana town of Gibsland, nearly halfway between Shreveport and Monroe and right in the middle of nowhere. The town was named after a slave owner named Gibbs whose plantation it had been. Its only claim to fame was that Bonnie and Clyde had been killed just south of town in 1934. Townspeople still relished the infamy. Gibsland was a place where the line between heroes and villains was not so clearly drawn.

Although the town was already contracting, downtown retained a one-of-each-thing, much-of-nothing quaintness. There was one grocery store and one dry cleaner. One feed-and-seed and one drugstore. One dry goods store and one bank. One restaurant and one furniture store. One stoplight and one policeman.

It was a place with whites and blacks mostly separated by a shallow ditch and a deep understanding. Main Street cut through town from north to south and was flanked on both sides by most of the white community. Most blacks, like my family, lived on the western side of town.

Ours was a small, rent-to-own house on a narrow street – Third Street – that ran down a gently sloping hill. The street was populated with young families and old couples – everybody nickname-close. I wasn’t only the youngest boy in my family, I was the youngest boy in the whole neighborhood – not just my mother’s baby, but everybody’s baby, a fact expressed in a nickname of my own: Char’esBaby. That was what everyone but the single mother next door, a round woman with three round sons, called me. She insisted on Chocolate. She said that my skin looked “just like chocolate.” Every time she saw me, she met me with a smile and a request: “Come here and give me some sugar, Chocolate.”

Our house had a small, uneven yard dotted with fire ant mounds, prickly weeds, and clover patches, but little grass. It had an unpaved driveway and a three-foot-high front porch with no steps. This meant that you had to either jump up onto the porch or, as was more often the case, enter through the back. My mother pleaded with my father to build steps. He could easily have done it, construction being his trade and all, but he never did.

A lone pink-flowered mimosa tree stood near the street, stunted and distorted, bowing to passersby and drawing a charm of hummingbirds. A large sweetgum tree marked the property line, its muscular, runoff-exposed roots cascading into a ditch – twisting terrain for secondhand action figures and a handful of Hot Wheels. Wasp nests dangled from the overhangs. Paint strips peeled away from the house like husks from corn. Son of a Bitch, a dog my brothers found – they begged my mother to let them give it its literal name – sought refuge in cool spots under the house.

I don’t remember much about my brothers in that house, only that I shared a room with my oldest brother, Nathan, and that my next-to-oldest and next-to-youngest brothers, William and Robert, shared the adjoining room.

Theirs was the only bedroom in the house with a television, up on a chest of drawers between twin beds. That meant that their room served as a den by default. We had pillow fights and tickle fights in that room. We draped sheets over box fans to make inflated tents. We watched Soul Train, lighting up at the dancers getting down, joining in as they ended the show: “Love, peace, and soooouuul!” There was a hole in the wall that joined our closets, just big enough for me to squeeze through and make repeated “surprise!” entries into William and Robert’s room. To do so, I had to crawl over a bunch of old guitars that littered the closet floors like limbs blown down by a heavy storm.

Nathan told me that they belonged to my father, that he had been in a band, that one night after a gig and a little too much liquor my father and his bandmates had a car wreck. My father was driving. Someone in the band was killed in the crash. My father did a stint in prison for his part in it. When he got out, he never played again. That’s when he took up construction.

Copyright (2015) by Charles M. Blow. Not to be reproduced without permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.