Soleiman Faqiri’s family is still looking for answers.

They want to know why, less than two weeks after he was arrested, the 30-year-old was found dead on Dec. 15 while in solitary confinement in an Ontario jail.

“We want to know why my brother died,” Soleiman’s brother, Yusuf, told CBC News late last year. “Why did Soleiman die? How did Soleiman die? That’s what we’re looking for.”

Yusuf said his brother, who was jailed on aggravated assault charges that were later dropped, has schizophrenia.

The family was repeatedly denied requests to visit Soleiman in prison on the pretext that he was held in solitary confinement, which in Canada is known as “segregation,” Yusuf said. After Soleiman’s death, Yusuf said his brother’s body was returned to the family covered in bruises and with a large gash on his forehead.

Soleiman “was restrained with his hands behind his back, pepper-sprayed and had a spit hood placed over his head before his death at the so-called super-jail,” according to CBC News. These are the harsh and traumatic conditions prisoners may find themselves in when they are put in solitary confinement in federal and provincial prison facilities across Canada.

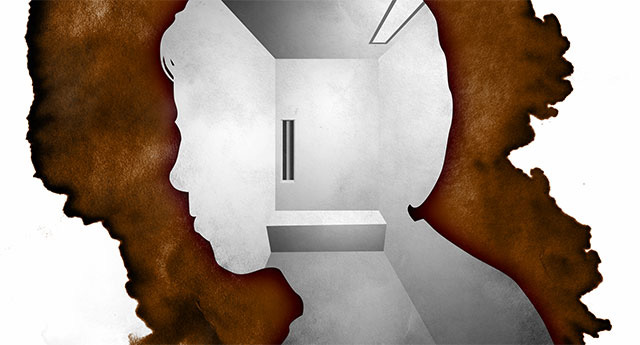

Prisoners held in segregation can be kept alone in a single cell for up to 23 hours per day, with the lights on constantly overhead. Some lack clean clothes or blankets, and many never have access to psychological care. They have little to no human contact for days, months and sometimes even years.

But a push to outlaw the practice is gaining momentum after a handful of recent cases like Soleiman Faqiri’s have shone a light on the irreparable harm and deep physical and psychological scars that solitary confinement can inflict.

“It’s 2017. It’s time for Canada to say, look, this is an inhumane … practice that should not be permitted in our country,” said Sukanya Pillay, executive director of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA).

Late last year, Ontario’s Human Rights Commissioner raised alarm about the case of Adam Capay, a 23-year-old who had been held in solitary confinement at a jail in northern Ontario for more than four years.

Capay, a member of the Lac Seul First Nation, was being held in a cell alone for 23 hours each day, and the light in his cell was never turned off.

Renu Mandhane, the human rights commissioner, told CBC News that Capay showed signs of self-harm when she met with him, and he displayed difficulty communicating and distinguishing between night and day.

Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne described Capay’s case as “extremely disturbing,” and the government moved to set up an independent investigation into the use of solitary segregation across the province.

Howard Sapers, Canada’s former federal correctional investigator, was appointed to lead that inquiry. He told Truthout that his general impression, which is not specific to Ontario, is that “segregation has become a default strategy for managing difficult individuals” in Canada. “There’s good cause to review the use of segregation and to look particularly at the use of segregation involving special needs or high needs individuals, specifically I’m talking about those with mental health concerns,” Sapers said.

Sapers said he intends to deliver a report on March 1 looking into oversight and accountability, staff safety and opportunities to reduce the use of segregation. He then expects to submit a more in-depth report on overall corrections reform 120 days later.

“Has the legal requirement to look for alternatives been met, and has the requirement to return people back to general population as soon as practical been met? Or are people simply being segregated because it’s the path of least resistance? Those are the questions I’m going to be asking.”

Tragic Cases

Capay’s case wasn’t the first time a tragic event has raised a debate around the use of solitary confinement in Canada — and some say these cases point to a disturbing trend of frequent use of solitary confinement in Canadian prisons.

In 2007, Ashley Smith hung herself in a jail cell in Ontario while prison staff looked on. The 19-year-old suffered from mental health issues and she had been held in segregation in youth and federal prisons for more than 1,000 days when she died.

“She was often given no clothing other than a smock — no shoes, no mattress and no blanket. During the last weeks of her life she slept on the floor of her segregation cell,” an inquiry into the circumstances surrounding her death, which was ruled a homicide, found.

The inquest recommended that Canada abolish indefinite solitary confinement, limit any period of segregation to no more than 15 days, allow a mental health professional to conduct daily visits to all female prisoners in segregation, and provide all female prisoners with access to a psychologist within 72 hours of being admitted into a correctional facility.

Canada’s previous federal government disputed that inquiry’s findings and argued that segregation was necessary to protect the safety of prison staff and the prisoners themselves.

But in a mandate letter to Canada’s Minister of Justice and Attorney General after winning the federal election, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau instructed Jody Wilson-Raybould to implement the recommendations stemming from the Smith inquest. These included restricting the use of solitary confinement and improving the treatment of prisoners with mental illness.

Prisoners can currently be placed in two types of solitary confinement in Canada. According to the government, disciplinary segregation is used to punish bad behavior and encourage prisoners to respect “the good order” of the detention facility. Administrative segregation, meanwhile, should only be employed “for the shortest period of time necessary, when there are no reasonable alternatives and in accordance with a fair, reasonable and transparent decision-making process,” the government has stated.

Pillay says that while Canadian officials do not use the term solitary confinement, that is exactly what “segregation” is. The CCLA is currently challenging Canada’s use of solitary confinement in federal court as being unconstitutional.

“We don’t want to wait for the next Ashley Smith or Adam Capay to act,” Pillay told Truthout.

“It reaps no benefit and it causes a great deal of harm and it reflects on who we are as a society, in addition to the very direct and serious harm that’s done to the prisoner. So this is a serious concern for us.”

“Systemic Overuse”

The Ontario Human Rights Commission also recently described what it called an “alarming, systemic overuse” of segregation in Ontario. About 19 percent of prisoners — or 4,178 people — were put in solitary at least once in a three-month period, while 1,383 of these spent 15 days or more in segregation.

The data also showed that 38.2 percent of prisoners placed in segregation had a “mental health alert” on their file.

Last March, data provided by corrections officials as part of one of the commission’s cases showed that more than 1,600 prisoners were held in solitary at two provincial jails over five months.

According to a report published at the University of Toronto in 2012 on the treatment of female prisoners with mental health issues, one prisoner known as K.J. spent five to six years in segregation, including an uninterrupted period of 21 consecutive months.

K.J. told the authors of the report that “some of the staff really challenge you … they come in there like ‘oh I’m going to mess with her'” and she reported often having her personal belongings taken away by prison staff when put in segregation.

Jean Casella is the co-founder of Solitary Watch, a project that investigates, documents and spreads information about the widespread use of solitary confinement in the United States. She said solitary confinement has been shown to have extremely detrimental psychological and even neurological effects on prisoners, ranging from anxiety, depression, visual and auditory hallucinations, and difficulty communicating with others, to suicidal thoughts and self-harm. While 5 percent of all prisoners in the US are held in solitary, 50 percent of all prisoner suicides take place in solitary confinement, Casella said. “That statistic alone, I think, should be compelling reason to stop using it,” she told Truthout.

Casella said solitary confinement is deployed as “a control measure of first resort” that is often used in response to untreated mental illness among prisoners, or to contain prisoners deemed “in need of protection,” such as LGBTQ prisoners, for example.

“The important thing in both countries is that no judge or jury is deciding if people need to be sent to solitary. It’s completely a decision being made by the prison staff,” she said, adding that this decision is largely arbitrary and often unfair.

The former United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture has cautioned that youth and prisoners suffering from mental health issues should never be placed in solitary confinement, and no one should be held in solitary confinement for more than 15 days.

“Segregation, isolation, separation, cellular, lockdown, Supermax, the hole, Secure Housing Unit … whatever the name, solitary confinement should be banned by states as a punishment or extortion technique,” Juan Méndez said in 2011.

Solitary confinement “can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment when used as a punishment, during pre-trial detention, indefinitely or for a prolonged period, for persons with mental disabilities or juveniles,” he said.

A Drop in the Use of Segregation at the Federal Level

In contrast with provincial jails, Correctional Service Canada statistics showed a drop in recent years in the use of segregation at federal prison facilities: between April 2014 and June 2016, administrative segregation decreased by 41.8 percent, from 780 to 454 prisoners.

Federal prisoners also spent fewer days in administrative segregation during this time. Pillay said this drop in federal prison segregation, if accurate, shows that the practice is not needed in Canada, and practical alternatives must be considered. “If there is the will to reduce its use, it can be done,” she said.

According to Casella, while organizing against solitary confinement has a long history in the United States and important steps have been taken, there is more attention paid by comparison in Canada when a prisoner dies in solitary confinement.

“I’ve actually been impressed by how much press coverage and response a death in custody gets compared to here. People die in solitary all the time in the United States,” she said. She added that the potential for change in Canada is there, if the public makes the issue a priority.

Sapers, meanwhile, said he is encouraged that the Ontario government is already moving ahead with some reforms, including infrastructure investments, and hiring additional staff to deal with segregation specifically.

In October, the province said it would only use segregation “as a measure of last resort,” and a 15-day limit would be placed on disciplinary segregation, down from the previous 30-day maximum.

“I’m convinced that the government of Ontario wants to make substantial and permanent changes in how correctional services are provided in this province. If I wasn’t convinced of that, I wouldn’t have taken the job,” Sapers said.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.