The home of Cássia Sales and her family was destroyed by a World Cup light rail project, which is continuing to displace members of her community of 42 years in Fortaleza, Brazil. The residents of Trilha do Senhor, a community along old train tracks, have been weaving a social fabric for over 70 years. They depend on the hospitals and schools nearby, and they own the land.

But the light rail project, the VLT (Veículo Leve sobre Trilhos, in Portuguese), has not destroyed her or her community’s resolve to come together as a movement and win thousands of reductions in the evictions the city has claimed necessary for the train route. As part of the Movement to Fight in Defense of Housing (MLDM) in this large northeastern city, Sales and numerous other community members and activists successfully fought for the guarantee of compensation for their homes when initially none was offered. They are also working to ensure the government follows through on its promise of replacement housing.

The VLT was originally touted by the government as a way to make an exciting improvement in the city’s “urban mobility” for the World Cup. According to government press releases and the website of the international football governing body FIFA, the VLT would allow tourists staying in nearby hotels to more easily reach the World Cup stadium.

Over a year after the World Cup, this VLT project – among numerous other World Cup projects throughout the country – remains far from complete. According to activists on the ground, even the basic rails have been barely laid down. Now after a yearlong pause, construction has recently resumed, and the government claims that if there are no further interruptions, it will be ready by 2017.

“We fought against the violations of the powerful and throughout the fight we were able to change a lot.”

The proposed VLT does little to serve the transportation needs of Fortaleza’s residents, however. Contrary to the government and FIFA’s story, local residents argue that this project is a form of social cleansing. It is set to run approximately eight miles from Parangaba to Mucuripe, affecting 22 communities in its path, totaling around 2,500 families who are being forced to move, according to MLDM.

The Sales family’s home before it was demolished. (Photo: Nolan Morice)

The Sales family’s home before it was demolished. (Photo: Nolan Morice)

The city’s population has been waiting for the completion of a robust subway system, “o Metrô,” since the transportation department formed Metrofor 27 years ago with that intention. The only line currently running with regular frequency for in-city transportation, however, is the South line, “Linha Sul,” and four other lines are being implemented in stages. These lines were planned with in-city transportation for residents in mind; in contrast, the VLT’s route runs from hotels to the stadium.

Though it is clear that the city needs serious transportation improvements, the government used the World Cup, and has been using the VLT project, as a way to remove working-class residents without fair process or compensation. The domineering and arduously bureaucratic approaches of the city’s government have prioritized development for the upper class and tourists over serving the transportation needs of longstanding communities.

The government and FIFA may have been able to sweep these violations under the stampede of World Cup tourists if MLDM hadn’t organized and demanded otherwise.

But the fight for reducing evictions and protecting civil rights is far from over. “We didn’t just sit back and do nothing,” said Sales, who has belonged to MLDM since the communities started organizing against the removals in 2010. “We fought against the violations of the powerful and throughout the fight we were able to change a lot.”

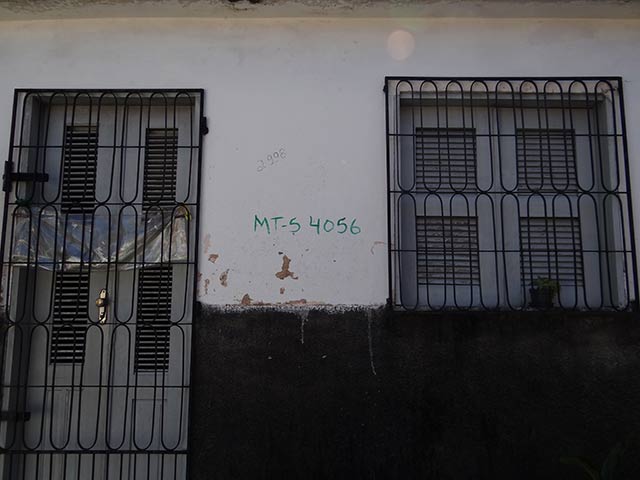

House marked for removal in Comunidades do Trilho. (Photo: MLDM)

House marked for removal in Comunidades do Trilho. (Photo: MLDM)

Cássia’s Story

After being forced to leave her home in Trilha do Senhor, one of 22 communities along the proposed route, Sales fought for proper compensation and replacement housing, and eventually found a place in a neighborhood eight miles from her home community. With her significant involvement in the movement since the beginning, and in turn, strong community-organized support, Sales was able to win about 98,000 reais ($24,800) in compensation. This was a big win in comparison to the 39,000 reais ($9,900) originally offered by the state.

In general, the government has only been offering 15,000 reais ($3,800) or less to families for the houses in the area. “Where will you find a new place to live that costs only 15,000 reais?” said Gláucia Sayuri Takaoka, an activist involved in MLDM. The average price per square meter for real estate in Fortaleza was 3,600 reais last October.

Families learned that they were facing eviction not from someone coming to inform them, but from news reports.

But even Sales’ compensation doesn’t adequately cover the expense of relocating a family. She was forced to take out a loan because it wasn’t enough for a new place. On top of that, the government has then been requiring the families to pay IPTU, a Brazilian urban real estate tax, for the land from which they are being evicted. This means in order to receive the government compensation, families first have to pay the IPTU for all the years they’ve been living there because they don’t have papers saying they own the land, even if they have been living there for decades.

“It’s really ridiculous because one time they say the land isn’t theirs, and the other time, they ask for money for the land,” said Gabriela Zaupa, an activist from Fortaleza and MLDM member. “That makes people feel really vulnerable every time the government is asking for more and giving less.”

In 2010, the families in Trilha do Senhor learned that they were facing eviction not from someone coming to inform them, but from news reports and the discovery that outsourced companies had begun marking their homes for removal without their consent, according to MLDM. This was when they started organizing and learning what they could do to stop this, and as they met with some of the 22 communities affected by the light rail project, they then founded the Movement to Fight in Defense of Housing.

“The movement remains focused on the struggle for adequate housing,” Sales said. “I believe that through the struggle, the families who remain in the train track communities, in the future, will have gained their space and their deserved respect.”

Activist Victories and Government Roadblocks

After MLDM demanded the government make an alternative route proposal for the VLT, the number of families facing displacement was reduced from an estimated 5,000 to about 2,500, housing activists said. In addition, temporary compensation was initially 200 reais per month before MLDM got it raised to 400. While a success for housing activists, the doubled compensation still only covers the cost of a single room in the city, far from sufficient for an entire family.

Another major gain for MLDM and the threatened communities was getting the government to promise alternative housing. The families could thus either choose a government house through Minha Casa Minha Vida, a federal government housing program for low-income families, or additional compensation for their home.

However, none of the houses for the train track communities have been built, even though a government press release stated that over 1,000 “processes” have been completed, meaning those inhabiting over 1,000 homes have already been evicted before construction resumed. Furthermore, some of those already evicted haven’t even started receiving the 400 reais per month to be used to rent temporary housing.

Sales is concerned those replacement houses are never going to become displaced families’ homes.

“I sincerely do not believe that the government intends to fulfill these promises of houses from Minha Casa Minha Vida,” she said.

During the World Cup, the streets were so militarized people were afraid to even go out.

The two housing options the city has promised are in the neighborhoods of José Walter and Cidade 2000. The José Walter houses would be about 30 miles from their previous homes for some community members, while at the site of the closer housing, in Cidade 2000, the city has not started construction. In order to receive the promised housing, community members must prove they have a regular income, which many do not have.

The state has said that the number of families facing removal has been reduced, but there is no new estimate provided. This reduction is then qualified by stating that it could increase if other construction is determined necessary or if there are project changes. Government press releases state that the VLT is 50 percent complete, while activists in the communities believe it to be much less than that. In any case, the danger is that the government has left open the possibility for increased evictions.

The State of Ceará’s Secretary of Infrastructure (SEINFRA) now has a pamphlet on its website explaining the VLT project and the removals that includes cartoons of neighbors discussing why they have to leave, compensation and replacement housing, though the reality outside this cartoon world has been much different. Government promises have been broken and guarantees, as well as basic information, have been received only after a tremendous fight from the communities.

According to the pamphlet and the law, the government is required to provide housing, sufficient compensation for their homes and temporary rent assistance to the displaced residents. As a result of broken promises to date, however, many MLDM members are skeptical that the government will follow through on these obligations.

For example, after a public hearing in April, the government suggested creating a working group involving government representatives, people from the communities and MLDM members, which met for a couple months. However, essentially nothing came from the meetings for the community, and the government stopped the meetings in June citing a change in staff.

Displacement of Working-Class Families: Development for Whom?

Trilha do Senhor established its community over 70 years ago, in what is now one of the wealthiest neighborhoods of Fortaleza, Aldeota. Residents of Trilha do Senhor and housing activists claim the city’s intention is to remove working-class residents from wealthier areas.

The World Cup provided an excuse for the government to “clean the city in the eyes of the tourists,” Zaupa said. “So they came up with a lot of projects all over Brazil to remove those kind of communities they didn’t want to see.”

The government continues to use other development projects, such as a tunnel and overpasses, as a way to remove community residents. Some families that were originally able to stay despite evictions are now being told they must also move.

“That’s actually something we said from the beginning, that people should fight for what they have now because once this first project is done, others would come because they don’t want people there,” Zaupa said. “They want buildings, or something that gives investment to the upper class. They don’t want people who don’t have a lot of money in those areas.”

Other Tactics and Resistance

Aldaci Barbosa, another community that has faced displacement from the VLT project, took a different approach in its resistance and negotiation due to the circumstances in the community, according to resident and activist Jersey Oliveira de Albuquerque.

Community organizers saw that families were individually negotiating with the government and “resolved to negotiate collectively before the government weakened us,” Albuquerque said.

They have also made significant gains, including an 80 percent decrease in potential removals in the area, better compensation and promised housing close to the community, as well as keeping the health center and town hall where the community center was previously. In total, about 600 families took part in organizing, which primarily occurred through the residents’ association.

Significance of Protests Leading Up to and During the World Cup

Though Fortaleza was one of several Brazilian cities affected by the displacement, extravagant spending and violent repression associated with the World Cup, the city and the injustices faced by working-class residents and protesters who took to the streets received little international media attention.

While many speculated as to why the protests weren’t as strong during the World Cup as in June 2013, when they caught the world’s attention with their magnitude, those on the ground said the streets were so militarized, people were afraid to even go out.

One protest that occurred at the FIFA Fan Fest didn’t face as intense repression due to all the tourists outside the game, and the protesters’ ability to blend in, while other protests were completely shut down with extensive arrests.

Many people avoided the protests out of fear.

“The police made it very difficult to protest,” Zaupa said. “That’s actually a very dangerous thing to happen because if you can’t even protest, what can you do?”

Jeffrey Rubin, an associate professor at Boston University, whose research has focused on the history of grassroots activism in Brazil and its contributions to democracy, noted that Brazil has a long historical trajectory of social movement activism, particularly since the late 1970s, when civil society organizing surged and new social movements focused national attention on a wide range of inequalities.

The outbreak of protests on the streets in 2013 was a natural result of this trajectory, according to Rubin. He said the protests at the time of the 2014 World Cup were then a second, very significant moment in that trajectory of activism, and added that the reconfiguring of sports in the public perception was also crucial.

“People are not just saying, ‘World Cup! Wow! We’ve made it,’ which is what leaders imagined they would say,” Rubin said. “Rather, ordinary Brazilians are saying, ‘World Cup! Wow! We love it, but this is a moment when all sorts of really difficult or downright horrible things are happening in our daily lives.'” In a context of ongoing economic hardship, a few cents added to bus fares can become national news alongside the World Cup, he added.

“That’s the connection-making that the trajectory of social movement activism inspires,” Rubin said. “And it shapes whether democracy can bring about real change. So what happens now in Brazil is really relevant to what happens in Latin America and what’s possible in the world.”

Where Are the Families Now and What Does the Future Hold?

The residents who have already been forced out of their homes and communities have wound up in various situations. Some have been successful in finding houses, but usually very far from where they lived before because it’s cheaper.

“Then they are far from their jobs, far from their schools, far from the hospitals, far from their neighbors, their friends – it’s tough and really sad,” said MLDM activist Takaoka.

Others live with their relatives or friends who offer to help. But MLDM is still organizing, whether against the VLT project or another threat.

It’s important for the community struggles to continue to gain international attention, MLDM said. The impact of the protests against FIFA and government priorities in Brazil and in the international community remains a test for the future, particularly as the Olympics come to Brazil in 2016.

Questions remain for the housing activists and all communities impacted by these infrastructure issues. Will Brazil’s protests against how the World Cup came to Brazil hold governments and FIFA, along with other major sporting institutions, accountable to democratic processes in the future? How can public transportation and sporting events develop without dismantling tight-knit, working-class communities? How can the resistance of groups like MLDM set an example for future communities fighting displacement by major sporting and government interests?

“It’s good that the whole world knows what’s really happening here in Brazil, in Fortaleza, because what the mainstream shows isn’t what’s really happening in the streets,” Takaoka said.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $205,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.