Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

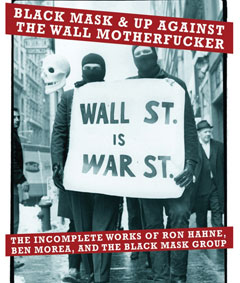

“Black Mask & Up Against the Wall Motherfucker:

The Complete Works of Ron Hahne, Ben Morea and the Black Mask Group“

Oakland: PM Press, 166pp, $15.95

I recall seeing the legendary Ben Morea only once. It was at a Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) national convention, probably in 1967, and he appeared about to explode. People on each side of him held him down as he attempted to rise, apparently in response to what was being said on the stage, although he didn't shout (as I recall) and the particulars were a bit mysterious.

Very Morea, in other words. By 1968, black and red flags crossed at the front of the SDS convention, and it seemed a fine moment for anarchism … and the global revolution. My own Radical America magazine, syndicalistic by nature, had begun planning the translation/publication of “Society of the Spectacle,” the Situationist text (by the time it happened, SDS had imploded), and documents as well as analyses of the crossover from student radicalism to black power and working class resistance, not to mention feminist initiatives. “Marxism” was much too small for all this.

Thus, Morea and his comrades. He was, as we learn in the last section of the book (a 2006 interview reprinted here) an artist who experienced his teen years in Manhattan, somewhat older than new left types (like me). A substance abuser, he spent some time in jail, emerging to grasp onto the Living Theater as lifeline and radical art of some kind as his mission. Dada, surrealism, Zen, and more fed the mix, and he formed a group with like-minded types in the middle 1960s. Black Mask, (co-founded by Morea and Ron Hahne, who otherwise disappears from this publication), a pamphlet that looked like a tabloid, first appeared in 1966. For those days, it was wild.

So was the group. They believed in a kind of anti-art, a disruption of galleries and exhibitions that represented the official art world, offering guerilla theater and bold statements in Black Mask, sold for a nickel or given away free. Likely, the most famous incident involving the group was not theirs: Valerie Solaris' attempted assassination of Andy Warhol. Morea not only wrote a pamphlet defending her act and her politics (she was a brilliant and extremely funny polemicist), he probably left a gun around where she could grab it. Because Warhol was seen as corrupting the possibilities of avant-garde art, he was (and is, in the interview) seen as an appropriate target.

Much of the rest of the story belongs in that same time period, when experiments with LSD were likely to accompany the boldest antiwar activity; when rock promoter Bill Graham represented the performance music industry and in response The Family (a broader entity around Morea and Black Mask) could seize the stage, enforcing a free night of music for eager youngsters; and when resistance against police seemed to rise to the occasion, at least sometimes. If anyone inspired the Affinity Groups that accompanied demonstrations and confronted the law, for better or worse, it was the group that was called UAW/MF (they accepted the title without calling themselves that).

They also promoted the merger of the counterculture with the homeless, on the Lower East Side, thus offering a precursor to Occupy. That on the positive side. The negatives should not be ignored. In retrospect, they appear larger than they did at the time.

When UAW/MF disrupted peace-poetry readings because old-timers were of Popular Front vintage; when pacifists found themselves outmaneuvered by macho tactics; when efforts to build coalitions were damaged and, in relation to the young feminist movement, made nearly impossible, the limits of anarchist tactics had been more than reached. The nearness of possible revolutionary transformation justified what could not otherwise be justified or perhaps even comprehensible. It should also be added: the degree of ego was too evident. Black Maskees could not work with Situationists (even more conspiratorial and egotistic) or with anarchist chieftain Murray Bookchin (despite his brilliance or because of it, urgently seeking Bookchinites, his own camp followers), making issues often seem less political than personal. It was a turf war.

Readers can judge for themselves, because this book reprints the entirety of Black Mask, albeit not in the tabloid format, along with assorted leaflets. The documentation is terrific and worth the price alone.

Matching Opportunity Extended: Please support Truthout today!

Our end-of-year fundraiser is over, but our donation matching opportunity has been extended! All donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar for a limited time.

Your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. Your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. As Trump attempts to silence dissenting voices and oppositional nonprofits, reader support is our best defense against the right-wing agenda.

Help Truthout confront Trump’s fascism in 2026, and have your donation matched now!