Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

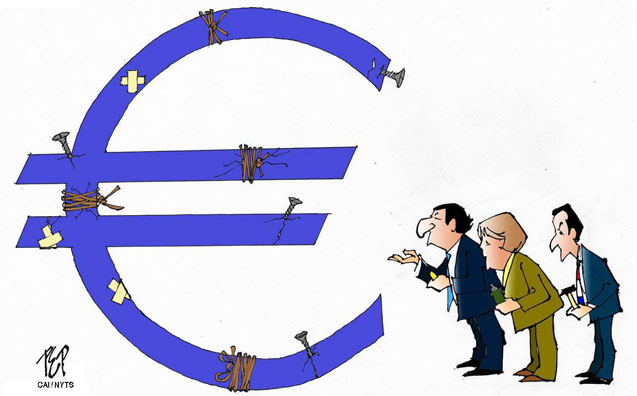

One of the key arguments made by the proponents of fiscal austerity, even in a deeply depressed economy, has involved a sort of macroeconomic version of Pascal’s wager. Yes, the more open-minded admit, borrowing costs are very low in the United States and Britain. Yes, the arithmetic suggests that cutting spending now will do very little to improve long-run fiscal prospects. But you never know — maybe the last trillion dollars of spending will be what causes a sudden loss of market confidence, turning you into Greeeeeeece. (Cue scary noises.)

Leave on one side the enormous difference between countries that do and don’t have their own currencies (and debt in their own currencies). Let me instead point out that there are other risks.

Specifically, if allowing an economy to remain persistently depressed reduces long-run growth prospects — and there’s pretty good evidence to that effect — then austerity in a depressed economy has enormous costs, and may even lead to a vicious circle of shrinking potential leading to even more austerity and so on. Indeed, maybe that’s happening to Prime Minister David Cameron’s government right now.

So will the austerians admit that they might be making a terrible mistake; that far from safeguarding the future, they may be destroying it?

Macroeconomic Chutzpah

Chutzpah, according to the old definition, is when you murder your parents, then plead for mercy because you’re an orphan. I found myself thinking of that definition when reading Justin Fox’s description of recent remarks by Jean-Claude Trichet.

“Jean-Claude Trichet, now a few months into retirement, has no regrets about his eight-year tenure as president of the European Central Bank,” wrote Mr. Fox, the editorial director of Harvard Business Review Group, in an article for HBR.org. “At least, that’s what he said at Harvard’s Kennedy School Thursday night when a student asked him point blank. ‘I don’t regret anything,’ was the response. But listening to the full talk … it was clear that Trichet did regret something about the last few years. He regrets that economists didn’t give him better advice.”

Mr. Trichet laments what he says was the failure of macroeconomics to yield useful guidance in the crisis. On the whole, I’m sympathetic to that view. A lot of modern macro proved not just useless but actually harmful, because it undermined the workable macro consensus we used to have — a consensus that could and should have led to a better response.

But from Mr. Trichet? After all, his hallmark during the crisis was his willingness, even compulsion, to throw the things we actually do know out the window. He tossed everything we know about aggregate demand out in favor of the fundamentally implausible (and now failed) doctrine of expansionary austerity.

And now, having willfully rejected and ignored what macroeconomics had to say, he complains that macroeconomics doesn’t offer useful policy guidance. Awesome.

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Paul Krugman joined The New York Times in 1999 as a columnist on the Op-Ed page and continues as a professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. He was awarded the Nobel in economic science in 2008.

Mr Krugman is the author or editor of 20 books and more than 200 papers in professional journals and edited volumes, including “The Return of Depression Economics” (2008) and “The Conscience of a Liberal” (2007).

Copyright 2012 The New York Times.

Thank you for reading Truthout. Before you go…

…We ask that you take just a second to read this message.

We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. Since his inauguration last year, we’ve seen frightening censorship, a right-wing takeover of the news industry, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We need your help to sustain the fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.