In spring 2011, Hooman Majd did something gutsy. He packed his bags and, with his wife and infant son, moved to Iran.

His move came during the strained period following the disputed 2009 re-election of firebrand President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and violent crackdown on Iran’s reformist Green Movement. A string of suspicious nuclear scientists’ deaths, increasingly harsh economic sanctions and repeated warnings from Israel and the United States that “time was running out” to find a diplomatic solution to Iran’s pursuit of nuclear technology defined the tension-filled annus horribilis of 2011, when Majd, his Wisconsin-born wife and their not-quite-1-year-old son relocated from New York to Tehran.

Majd, author of the critically acclaimed The Ayatollah Begs to Differ (2008) and subsequent The Ayatollahs’ Democracy (2010) began writing about the Islamic Republic a decade ago after controls over dual-passport holders were relaxed, allowing him to travel frequently to Iran. Majd, the son of a diplomat and grandson of a prominent Ayatollah, was born in Tehran but raised around the world in Tunis, New Delhi, London, New York and elsewhere. After a career as a music industry executive, Majd gravitated toward journalism.

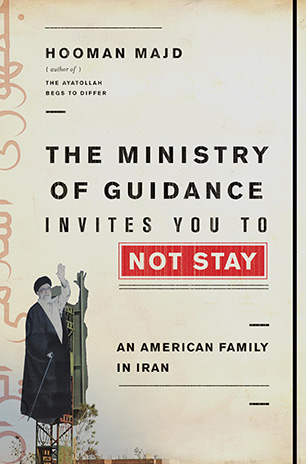

When Majd decided to take his family to Iran for an extended stay, he knew he would be writing about it, even if he was officially there “to spend time with his family.” The result of the Majd family’s near yearlong stay is his newly published book, The Ministry of Guidance Invites You to Not Stay: An American Family in Iran, in which Majd experiences an Iran quite unlike most people, certainly most Americans, envision. His descriptions – insightful, irreverent and often hilariously ironic – reveal a country that, like China in the 1980s, remains largely unknown to the West, shrouded in darkness but, as Majd writes, “Iranians are prepared to turn the lights back on at a moment’s notice.”

In October, Majd spoke to Truthout contributor Jon Letman on Skype about his new book and life in Iran.

Jon Letman: You wrote that your family tried to dissuade you from moving to Iran.

Hooman Majd: Yeah. Everybody was like, “You’re out of your mind.” The political situation wasn’t very good. All we heard about was Ahmadinejad and his craziness. Everyone was like, “Are you mad? You’re going to go to Iran for a year?” Maybe it was crazy, but it didn’t seem that way, to me anyway.

JL: Although you’ve said you wrote this book for yourself, I imagine you were thinking about your son reading this in the future too.

HM: Sure. I thought a lot about my son. I feel very strongly that, at a young age, it’s good to breathe the air, drink the water and eat the food of a place. Your body never forgets that. I spent the first eight months of my life [in Iran]. There will be that hidden memory of always having spent close to a year of his life in Iran. The air will always be familiar to him – and the pollution!

JL: You write about how your wife adapted to life in Iran more quickly than you expected.

HM: Yeah, I think so. If you move somewhere and don’t know people, you are going to be a little out of sorts, which had nothing to do with Iran. Other than the pollution and altitude, there wasn’t really a big culture shock. She knows Iranian culture and has experienced it on the outside. Although Iranian culture is somewhat different inside. She went around the city by herself; she took Farsi lessons, learned the alphabet. And by the end, she pretty much understood everything. Hopefully my son will have that experience too.

JL: In Tehran you lived in and area called Tajrish?

HM: Yeah, Tajrish, it’s pretty far north in the foothills of Tehran. I explain in the book why my wife wanted to get away from pollution, to be around trees and in that kind of neighborhood where there are parks and stuff like that. It used to be a village, but it is now very much part of Tehran. And it’s mixed – religious and that modern Tehran that we think of as being pretty secular and modern and people are living a very Western lifestyle. But there’s also very religious families who’ve lived there for generations and mosques, so that it’s an interesting mix.

JL: Would this book have been different had you been living in south Tehran or outside of Tehran?

HM: No question that it would have been different. If I was living in south Tehran, it’s a different lifestyle. You are surrounded by, generally speaking, much more religious, traditional people. We would have stuck out like a sore thumb, and we didn’t stick out at all in north Tehran – there were embassies around us, foreigners there; I’d go shopping in the bazaar for fruits and vegetables and run into the Norwegian deputy ambassador’s wife doing the same thing with her little baby. You see foreigners there, and at the same time people in chadors. But south Tehran would have been different.

JL: I found your new book to be very accessible.

HM: I hope so. It’s a story of a family that goes to a strange place that very few Americans know or have been to or, even if they have been, have an idea of what society is like. Plenty of journalists have been to Iran, but they spend four or five days in the capital and are isolated in their hotel with a translator. Also, it’s about a family, so anyone who has a family and has any kind of dual identity – you could be a Samoan who moves to America – understands what it means to be dislocated from your roots.

JL: There is a scene in the opening when you’re being questioned by two officials at Ershad – the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. When they want assurance you won’t write about the encounter, you tell them you won’t, admitting in the book that you lied to them. Are you concerned that what you write could come back to bite you?

HM: I have a funny feeling they probably knew I was going to write about it. It’s the kind of lie that I think is explainable. Despite what some people think – because I have been accused of being pro-regime – I have not actually censored myself. All the things that I’ve written I truly believe, whether it is an opinion piece or observation. I couldn’t live with myself if I was censoring myself in order to not get into trouble. In my first book I did a whole scene about smoking opium in Qom, and people were saying this is going to get you in such trouble. I won’t say I wasn’t a little concerned, but even in my interrogations in Iran I have never been asked. I just have to hope for the best. At the time I lied, but I felt it was important to write about it.

It has to be [real], otherwise there is no point writing it. I will have some criticism again with this book. I get criticized by the Iranian Islamic authorities for being anti-Islamic, and I get criticized by the Diaspora and people who are very anti-Iran here, the neocons, of being pro-regime and a “regime mouthpiece.”

JL: Your book has many examples of skepticism and real brash displays of anger by Iranians with the government. Are there people in Iran who are satisfied or happy with the government?

HM: Sure there are. There are people who owe their livelihood to the system. We’ve heard a lot about the Basij, the paramilitary force who’s repressing people who protested or whatever. There’s maybe a million of the Basij, and they get treated very well. They get to go to universities for free. They get scholarships. They get allowances, and they are completely dependent on the regime. … We’d be wrong to think that the entire population is anti-regime. I would say there is a good number who are, particularly in Tehran, and particularly in north Tehran, but in the overall 75 [million to] 80 million people, no, it’s not as if the people who are pro-regime or pro-government don’t exist.

JL: And yet, even among those who may be pro-government, do you think there’s a sense that they need a new relationship with the West, especially the United States?

HM: Absolutely. And that’s why someone like Rouhani won this election. It’s like, “We don’t want to overthrow the regime, but we do have to see some change. This is not working.” Even people who’ve done reasonably well understand well that the economy can’t keep going like this and we can’t be isolated from the world, the way we have been, as Iranians, in every respect. They just don’t like this constant sense of [being] in this cold war. It’s exhausting for the people.

JL: There were so many points in this book when I laughed. Your personality comes through, and it’s funny. People might not expect that.

HM: I don’t think people expect that, certainly not with a title like that, or maybe they do, with a title like that, because it is a bit of an ironic title and somewhat sarcastic. Real life is funny whether you live in Brooklyn or in Tehran. You could be in a war zone, and there are funny things that happen and people have written about those funny things, with humor and pathos, too. There’s sadness and drama and tragedy and all that stuff. But there’s also humor in everyday life, even under the most difficult circumstances, and it is my personality to reflect that as much as I can because the funny stuff is what makes it interesting for a lot of readers.

JL: With your music-industry background, you use musical references to such effect. Was that an intentional Spinal Tap reference in the book?

HM: It was indeed. “These go to eleven.” That’s one of my favorite movies – having lived through plenty of bands that have been too close to the Spinal Tap version of a rock band.

JL: Your previous book The Ayatollahs’ Democracy was much more political. For people who have never read about Iran, this is a great one to start with.

HM: I hope so. … It is impossible not to have politics in the book, but I try to relate politics to the culture – not to look at politics as it is. The second book was written in the aftermath of the Green movement, and there was a great interest in that. But the audience is always going to be smaller for political books.

When I was writing, I felt like this is my final chapter on Iran. … I’ll leave the next books for other writers who want to discover or write about their experiences. There have been plenty of other good books on Iran, but this is my trilogy, as it were. I’m not saying never, but I felt like this one had to be the most personal.

JL: You’re not thinking of a fourth book on Iran?

HM: (Laughs) An encyclopedia, 26 volumes? Circumstances could change, but right now I’m hoping my next book will be fiction. I haven’t done a novel, and I’d like to do that. It might have some bearing on Iran and Iranian culture and Iranian characters might be in the novel, but it’s not going to be specifically a nonfiction book about Iran unless something happens and my publisher and my editor say, “You’ve got to write another one, this one’s different.” But we’ll see.

JL: The ending of the book is bittersweet. It’s clear you feel conflicted when you leave Iran.

HM: Absolutely, that conflict has always been there for me. … There is this bittersweet thing that I leave, I go away. I have this dual identity, but people in Iran, my countrymen, they’re there. They go through it all – they’ve experienced the Iran-Iraq war, hardship, sanctions. They’ve experienced all that. It’s easy for us to sit here and talk about all that stuff without realizing there is a real human element to all of that.

I do feel sad about it, and yet I abandoned it of my own volition. So there is that pang of regret, I guess, and guilt is probably the word. I come here, and I can write. I have been [in the United States] most of my life, but I could go back. I could live there. I could be productive for Iran. But I also feel American – I am American – so it’s not a question of loyalty or nationalism. It’s like, “Where is your culture?” I guess it’s more here than it is there, because 95 percent of my life has been as an American and 5 percent as an Iranian or 10 percent or whatever you want to call it. But yeah, there is that sense that these are my countrymen and it is their country, but it is my country, too.

Mr. Majd’s comments were edited for length and clarity.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $31,000 in the next 48 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.