Haiti is rich in water resources, according to a 1999 study by the US Army Southern Command called Haiti Water Resources Assessment.

The US army studied Haiti’s water “to provide Haiti and U.S. military planners with accurate information for planning various joint military training exercises and humanitarian civic assistance engineer exercises.”

According this CBS report and many others, the US will soon face “a water crisis.” Americans are the world’s biggest water consumers – about 150 gallons each every day, compared to 40 gallons a person in the UK and less than the minimum of 13 gallons in poor countries like Haiti and Kenya. Some 36 states will face water shortages in the next three years, according to CBS.)

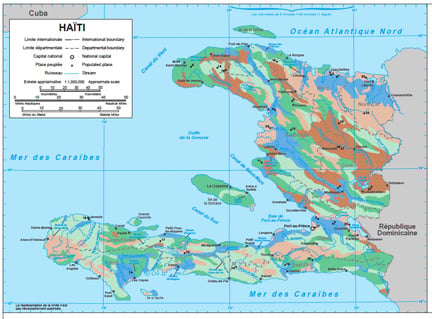

Haiti doesn’t have a water shortage, although it is in danger due to environmental degradation, lack of zoning, industrial, human and animal waste, and lack of sound distribution and management. Haiti’s water is also not equally accessible to everyone.

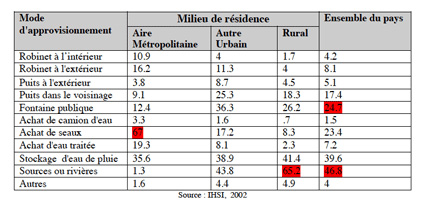

While the estimates vary, about 40 to 49 percent of Haitians supposedly have access to “improved” water, although a 2005 study by FOKAL showed that 65 percent of rural Haitians use rivers and springs.

Today, according to the new national water agency DINEPA (the Direction Nationale de l’Eau Potable et de l’Assainissement), 70 percent of the capital is reached public or private DINEPA outlets.

Port-au-Prince began providing its citizens with water almost 200 years ago, in 1841, from standpipes. By 1878, some homes – the more wealthy families – even had indoor faucets. The rest of the population got their water from the standpipes or paid water porters to bring buckets. In 1916, as the first US occupation began, the capital still had a respectable water system, according to author Simon Fass.

“Some 3,500 families, or a third of the population, were connected directly to the distribution system,” Fass writes in The Political Economy of Haiti which dedicates a chapter to water.

What Happened?

In short, the government water distribution system failed to keep up with the capital’s growth, with the increasing number of illegal connections, and with a de facto privatization that allowed a relative few to profit at the expense of the many powerless.

Among the phenomenon cited by Fass, “higher income consumers” in the 1970s and beyond “established clandestine private connections wherever nearby trunk lines permitted them to do so” and thus “contributed to further system deterioration.”

Many of those customers had (and have) small pumps. On days when CAMEP (Centrale autonome métropolitaine d’eau potable, the water authority for the capital which has recently been folded into DINEPA), supplies water to a neighborhood network, these households suction as much water as possible out of system and pump it into a private reservoir, to the detriment of all the non-pump subscribers, including public fountains.

A 1976 UN study, in which FASS participated, showed that CAMEP produced about 64 million liters a day, but lost almost half – 30 million liters – to theft, leaks and waste.

The study also showed that “the water industry” in the capital was big business. Those with connections sold water they didn’t actually purchase. High level Tonton Macoutes and their henchmen controlled access to fountains and standpipes, thus controlling and pushing up prices. Water trucking companies – unregulated by the state – also made handsome profits.

According to us at the UNCHBP [UN Centre for Housing, Building and Planning], water distribution was not a public service in the narrow sense of the phrase, but rather a sizeable private industry producing $3.78 million in value-added. About 26 percent of this accrued to 25 truckers, 32 percent to 2,000 connected households, 25 percent to 14,000 porters and 17 percent of CAMEP.

In Port-au-Prince, Fass writes, “relatively few suppliers with privileged access to advanced technology… amassed revenues from the many without access,” meaning there was “an annual transfer of US $1.22 million from 295,000 low income people” to “higher-income households of the political class.”

Water prices in the capital at that time “may have neen the highest urban water prices in the world,” Fass notes.

Alphabet Soup, NGOs and Fatal Politics

By the 1980s, an alphabet soup of ministries, agencies and committees in cities and the countryside – MTPTC, CAMEP, SNEP, POCHEP, CAEP, URSEP – had brought some improvements in terms of distribution and price, but not many. Theft, faulty maintenance, corruption and lack of investment, combined with the lack of sanitation, have all contributed to the systems degradation, and to Haiti’s cholera vulnerability.

According to recent figures, there are about 57,000 households in the capital connected to the water system, 33,000 of which are “active” or pay their bill. As in previous centuries, water distribution follows economic class and privilege – the wealthy have direct connections or buy tanker trucks full of water, the poor get water at fountains (for free or for a fee) or buy it from itinerant vendors.

In the smaller cities, by 2005 the SNEP (Service National d’Eau Potable, now part of DINEPA) was managing, or mis-managing, 28 systems. In other towns and hamlets, various committees managed pumps, fountains and cisterns built by communities, “non-governmental organizations” (NGOs) [1] and private citizens. Whether or not water is free or is sold, and at what price, varies from place to place but almost universally, where it is sold, poor pay more than the rich since they often buy by the bucket. There is no control on the price.

Nobody controls the quality of private sector water, either.

“There are so many NGOs in the country,” explained Dr. Maxi Raymondville of Zanmi Lasante/Partners in Health who works at the cholera treatment center in Mirebalais. “My colleagues call some of their interventions ‘folkloric.’”

All over the country, communities, towns, cities and regions are involved in bilateral agreements with foreign NGOs – “projects” – which might provide short- and even medium-term relief for water shortage or other issues, but the work is often not coordinated with the state or with each other.

“What we need is a strong state, and even a code of ethics from the state, to orient them so that they coordinate their work,” Raymondville told Haiti Grassroots Watch.

The NGO issue is related to another reason behind Haiti’s poor water system: successive governments have become more and more dependent on foreign assistance – loans and grants – meaning they are also subject to the whims of the “donors.”

For example, a $54 million loan agreement with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), signed in 1998, did not go into action until 2009 because Washington and other donors decided to “slow” all government aid in order to pressure the Jean-Bertrand Aristide government. The loan would have rehabilitated and expanded water systems in two of Haiti’s larger cities.

A 2005 report, Wòch Nan Solèy, showed clearly how Washington’s political agenda overruled public health.

Download English here.

Dr. Paul Farmer, who collaborated on that report, wrote – with colleagues – about the issue again in The Lancet (login necessary but article is free) earlier this month:

Some argued that such punitive policies were the prerogative of the donor countries, but blocking access to credit from the region’s largest development bank, a funder of public works throughout Latin America, should not have been the prerogative of the USA or any other government.

Thus, the origins of Haiti’s water problems are many:

rooted in governments that favored the wealthy or well-connected,

influenced by the fact that water was considered an “industry” more than a “public service” or public good,

strangled by irresponsible and inept governments, and

stymied by a foreign assistance-dependent approach.

Notes:

1. The term is a bit of a misnomer, since it defines using a negative, and because many of the larger NGOs receive a good deal, if not most, of their financing from government sources.

References:

Fass, Simon, Political Economy in Haiti – The Drama of Survival, Burnswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. 1988.

Fondation Connaissance et Liberté (FOKAL), Étude sur l’approvisionnement en eau potable en Haïti : Etat des lieux, propension à payer, mode de gestion et possibilités d’appropriation des systèmes d’adduction d’eau potable par les usagers, 2005

Also Read:

Behind the Cholera Epidemic: Introduction

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.