Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

Since election night 2016, the streets of the US have rung with resistance. People all over the country have woken up with the conviction that they must do something to fight inequality in all its forms. But many are wondering what it is they can do. In this ongoing “Interviews for Resistance” series, experienced organizers, troublemakers and thinkers share their insights on what works, what doesn’t, what has changed and what is still the same. Today’s interview is the 35th in the series. Click here for the most recent interview before this one.

Today we bring you a conversation with the co-executive directors of the Action Center on Race and the Economy (ACRE): Maurice BP-Weeks, who is based in Detroit, and Saqib Bhatti, who is based in Chicago.

Sarah Jaffe: Your organization is just getting off the ground. Tell us about the idea behind it and why you’re launching now?

Maurice BP-Weeks: The idea behind the Action Center on Race and the Economy is that there is lots of really great economic justice work being done looking at the role that Wall Street plays in everyday people’s lives. What we do here at the Action Center on Race and the Economy is do that work that goes after Wall Street and corporations (who we all know are extracting wealth from communities) with an explicitly racial justice lens.

Basically, the way that we have talked about economic justice work in the past on the left has been, when we bring race into the conversation, it is often through the lens of disparate impact. We say, “Bad guys do stuff at the top and it disproportionately affects people at the bottom.” What we do here at the Action Center on Race and the Economy is look at campaigns with a slightly different lens, saying that the actual function of how these companies operate is built on the extraction of wealth from people of color. It is not an afterthought; it is actually core to their business model. All the campaigns that we do live at this intersection of corporate accountability, Wall Street accountability, economic justice and race, with that particular lens.

Can you talk about some of the campaigns that led to this point?

Saqib Bhatti: Both Maurice and I have been involved in various Wall Street accountability campaigns for the past many years. We have worked together in many capacities. Some of the other campaigns that have informed this new project include the Refund America project, which had been focused on municipal finance deals and the increasing power of the financial sector within state and local governments, the way that drives austerity policies and drives impacts that are very problematic in communities of color, in particular.

It is not just the case that communities of color are disparately impacted by cuts to budgets. It is actually that part of how the most drastic, the most draconian cuts are justified is by doing them in communities of color. There are two salient examples: a lot of the work we did with the Detroit bankruptcy and work we are doing currently around the Puerto Rican debt crisis, two great examples of places where debt has been used to try to upend people’s lives, to undermine democracy, and we see that it starts with communities of color.

We have already seen them try to export the Detroit formula in other places. You create the formula by targeting communities of color, and then once you have that, you can also try to push in other places. Some of the other campaigns that have really gone into this work were the Hedge Clippers campaign, which has been focused around holding accountable hedge fund managers, private equity firm managers, and billionaires who are very often financial folks who are trying to control our politics and are increasingly on the wrong side of a whole host of issues, whether they are pharma bros who are increasing the price of pharmaceuticals or whether they are folks who are trying to push for the charterization of entire school districts.

Maurice can probably talk about some of the other work that we have done around housing and gentrification and various other issues like that.

BP-Weeks: The housing work has really spanned several years, back to the peak of the foreclosure crisis, where really I cut my teeth as an organizer in California going after Wells Fargo and some of the other banks that were foreclosing en mass on Black and Latino families.

The nature of housing in the country has obviously changed since the foreclosure crisis. A lot of our recent work has been around Wall Street buying up formerly distressed properties, foreclosed properties in bulk, often aided by HUD or other federal agencies. We, last year, ran a campaign that targeted HUD for their involvement in this program around distressed asset pools, which was basically just a program to, in bulk, hand homes off to Wall Street. We were making the case that these were mostly people of color who were foreclosed on and had these distressed properties. We shouldn’t give these homes right back to the people who caused the crisis. There is a huge need in Black and Brown communities for affordable housing and lots of people who really want to move back into these homes that were lost. We should be focusing on that instead of giving lots of properties directly to Wall Street.

We have also been targeting specifically this multinational organization Blackstone, which was both a key actor in that program and also is one of the largest single-family-home landlords. They are just buying up thousands upon thousands of homes in the country and we just think it is really troubling that this private equity group essentially has their hands on so much of American property.

We have continued beating the drum about Wells Fargo. Wells Fargo is an interesting case because it is not just that they foreclosed on so many Black and Brown families and caused that massive loss of Black and Latino wealth, not just through the foreclosure crisis, but through private prisons and the Dakota Access Pipeline investment and donations to police foundations and their role in the student loan crisis. They are sort of this perfect intersection of all of these ways of screwing over and extracting wealth from people of color coming together to create their business model, essentially. That has been part of the foundation of our Forgo Wells campaign.

Saqib Bhatti takes part in a press conference about Puerto Rico in Humboldt Park in Chicago in January 2016. (Photo: Grassroots Collaborative)

Saqib Bhatti takes part in a press conference about Puerto Rico in Humboldt Park in Chicago in January 2016. (Photo: Grassroots Collaborative)

A lot of these things had roots well before Donald Trump was elected. Over and over again we see these cuts to social services and these policies targeting communities of color. But they don’t only hit communities of color. They screw up the whole economy. And then somebody like Trump, in turn, manages to consolidate his own power by further blaming people of color. I wonder if you could talk about the way all of this has worked.

BP-Weeks: To me, the Trump administration is actually a perfect demonstration of our analysis. On the one hand, you have a group of people who are just outright racist, who are just pushing forward the most hateful, xenophobic ideas that you could possible imagine. And on the other side, you have this group of people who are some of the economic justice targets that we have been fighting for the past 10 or 20 years. Folks from Goldman Sachs, Steven Mnuchin, and that whole bunch.

In our analysis it makes a lot of sense that those two camps of people came together. There is a wealth extraction plan that they are pushing forward and the tool to do it is the racist hate language. Blaming the problems of the economy on Black and Latino [people], Brown folks and whoever else they can blame. It makes perfect sense that those two things are together and it is a really important calling for us to focus on race as a central piece of the work that we are doing. Because, if we don’t, it can be used as a tool against us.

Bhatti: I would add that one of the original sins of the Democratic Party going into the 2016 election was the failure of the last administration and the supermajorities in Congress to actually offer meaningful relief to struggling families in the aftermath of the financial crisis. The focus was on “How do we make sure that we can keep the financial system afloat?” and they left working families, struggling families behind.

One of the things that really is important about that is that one of the ways in which Wall Street ensured that they were able to push through their agenda was by racializing the issue. The homeowners who were facing foreclosure, they [were portrayed as] irresponsible Black and Latino families who got into loans they couldn’t afford and so they “didn’t deserve help.” The reality is, we know, that Black and Latino families were actually targeted with predatory mortgages.

But, the other side of that, though, is that while it is true that Black and Latino families are disproportionately the people who are impacted by the foreclosure crisis, in raw numbers it was a lot more poor white folks who were foreclosed on because there are a lot more poor white folks in the country than there are poor Black and Latino families.

The “white working class,” they very much were impacted by the same pro-Wall Street policies that were justified by scapegoating people of color. What is interesting now, of course, you had Donald Trump who really appealed to a lot of folks who felt left behind by the Democratic Party by saying the system is rigged. He wasn’t wrong that “The system is rigged.” It was rigged. Of course, it was rigged by the very people that he has put in his cabinet. So, it is this vicious cycle. As Maurice said, this is the perfect example of how race and class and racial and economic analysis go hand in hand and come together to give us the moment that we are in now.

I want to talk about “bargaining for the common good.” For people who are reading, who don’t know, explain what that means. What is bargaining for the common good?

Bhatti: Bargaining for the common good is this idea that when you have either public or private sector workers who are in unions who are bargaining, that they don’t need to and, in fact, they shouldn’t only limit their bargaining demands to issues that are workplace issues. That, in fact, workers lives don’t end when they go back to their communities, and what is good for the communities is also good for the workers.

With that in mind, workers should form long-term partnerships with community partners, with the communities in which they live. And for public sector workers, of course, the communities they live in are also the communities that they serve and that they should bring the demands of the broader community to the table when they walk into bargaining. By doing this, by politicizing bargaining and aligning their interests and by making bargaining something that is a platform for moving broader issues, workers can make their bargaining process relevant to the broader community. By doing that, there is both added power at the bargaining table for workers, and it also helps the community organizations and members of the broader community more effectively fight for a better future for themselves.

BP-Weeks: A couple of examples … one is in Los Angeles. It is spearheaded by a community group in Los Angeles, the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE). Along with SEIU 721, Scope LA, [and] lots of other partners in the Los Angeles area, [ACCE has] formed this campaign called Fix LA. As the municipal workers were coming up for contract, they said, “Let’s not just bargain around just the contract itself; how do these issues affect the community and specifically the Black and Brown community in south Los Angeles?” One of the things that they focused on was that the city’s sanitation workers had been cut by an enormous amount and it led to real problems in the city. More floods than normal because the city’s workers weren’t able to clean out sewer traps. Terrible roads and street lights, overgrown trees, etc. These things were all in south Los Angeles, all in Black and Brown Los Angeles.

So, this table came together to say, “The excuse that we don’t have money to hire back these workers is not acceptable. There actually is money. Los Angeles is in several bank deals. Let’s go after them, get that money back, and study other places where we are in bad bank deals as a way to fund a way to rehire these workers and expand the work that they do and fix Los Angeles. Money for our streets, and not for Wall Street.” That is an ongoing campaign, but they were able to win a restoration of local jobs based in south LA for Black and Brown folks. They were able to win a commission, a revenue commission, that looks at the bank deals that the city is in and how they can get out of the bank deals that are just costing them lots of money…. It is a real deep partnership [between ACCE and the SEIU] that lasts way beyond the contract. The contract was a piece in a broader puzzle.

Another example is the Chicago Teachers Union.

Bhatti: A lot of work the Chicago teachers have done over the course of the last couple of contracts cycles really is a good frame. In this past contract cycle where the CTU had just settled their contract this past fall, one of the key issues was tied to the budget — the Chicago Public School system does not have enough money coming in and it needs more revenue. The revenue is being held hostage at the state level by a governor that refuses to pass a budget unless he gets a series of anti-union reforms. In the meantime, you have this devastating budget crisis in which a lot of state universities are losing their funding. The ones that are impacted particularly hard are Chicago State University, which is the largest historically Black college or university (HBCU) in the Midwest. The other one is Northeastern Illinois University, which is the largest immigrant-attended school in Illinois. Those are the two that are being hit the hardest. Chicago State has been on the verge of closure for the past year. This time last year, every single person who worked there got a layoff notice.

But then, there have also been huge cuts to service providers. A lot of home care agencies have actually shuttered their doors because they are simply not getting payments from the state for work they have already done.

What was great about the Chicago teachers’ contract fight was that at bargaining they raised demands around the need to have new revenue. Last year on April 1, they went on a one-day strike. That strike was all about getting funding for the state budget. The big demand around the day of action was “We need the funding for our futures.” Through that, they were able to align a broad coalition of folks across the state and certainly across the city of Chicago who joined them in fighting for revenue.

In the end, when they settled their contract in October, the notice of the settlement came out at about six minutes before the midnight deadline. At the very last second Rahm Emanuel and the school board finally agreed to put new revenue at the table. That was a thing that they were holding out for, saying, “Unless more money [comes] into the district, no contract is worth the paper it is printed on because there simply is not enough money to be able to provide our students with the type of education that they deserve.” By leading with that and sticking with that, they were able to win new revenue and build long-lasting relationships.

BP-Weeks: We just hosted a conference on bargaining for the common good for racial justice. Bargaining for the common good is a tool that folks can use. We think that his tool can be used to push forward racial justice victories and racial justice outcomes. One of the things that we talked about at the conference is “What would it look like to put into the contract that the school district will refuse to bargain with any contractor who agrees to build the southern border wall?” or “What does it look like to put in the contract that the district will refuse to do business with any bank that forecloses on students during the school year?” Let’s also bring those to the bargaining table and get both unions and community members doing the work of having those conversations and pushing those things forward through bargaining. Not just using it [as] just a revenue tool — although it is extremely effective for that — but using it to ensure racial justice outcomes, in particular, too.

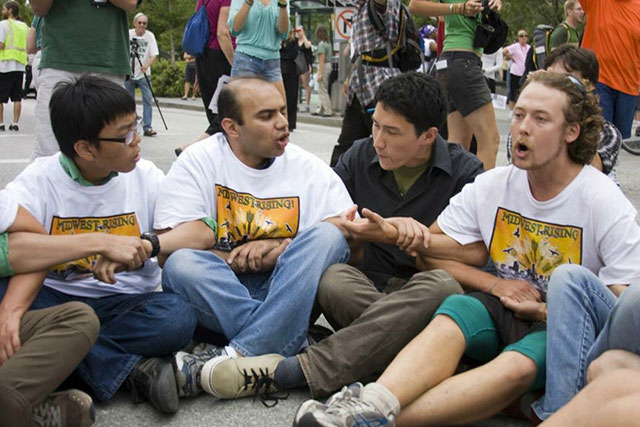

Saqib Bhatti takes part in the Midwest Rising conference in St Louis, August 2011. (Photo: Courtesy of Saqib Bhatti)

Saqib Bhatti takes part in the Midwest Rising conference in St Louis, August 2011. (Photo: Courtesy of Saqib Bhatti)

There is a tendency from some people to see police violence and prisons as an issue that cannot be part of an economic justice campaign. Can you talk about how your work has focused on those issues?

BP-Weeks: There is that tendency for folks to not see that as part of potential economic justice/racial justice campaigns. That is a real danger because both policing and prisons are smack dab at the intersection of economic justice and racial justice. We have been working on developing a campaign around this thing that we are calling “police brutality bonds,” which is a great example of this.

In several cases, when a city reaches a settlement for police brutality, the city doesn’t have or doesn’t want to pay out the cash out front for the settlement. The city finally settles with the family for $20 million or something like that. Instead of just writing a check for $20 million from the general fund, they instead issue a bond for that amount of money. As we know from other places and city budget campaigns, the bondholders always get paid. If you come into an economic crisis and you are running out of money and you have to choose where to put your dollar, the dollar goes to the bondholders, not schools.

So this police brutality bond is an interesting, very cyclical violence really. A physical violence incident then leads to ongoing economic violence for the communities that won’t get this money for their roads or communities not being able to fund their schools because you are paying the bondholders instead of the Black schools. These police brutality bonds exist in Chicago and several other cities. We are working on building a campaign to both bring that issue up more and to illuminate it.

Bhatti: Just to give an example of how this works, in Chicago there is one instance where there was a settlement for $28 million. The city bonded that out and as a result, they had to pay $25 million in fees and interest [on top of the $28 million for the settlement]. The amount of money they paid was actually almost double the original principal. In the case of Chicago, over the course of the last 13 years, the city has paid out $660 million in police settlements. It is unclear at this point exactly how much they have bonded out. But to bond most of that means … the city could be paying half a billion dollars in fees and interest. In the case of Chicago, the city also has structural revenue issues and there is constantly a threat of budget cuts. The thing that never gets cut is debt service. In Chicago, when there are cuts to services, you can be sure it is in the Black and Latino neighborhoods on the south and west sides, and the investment has gone on the north side.

The other thing we are starting to look at is the connection between private prisons and Wall Street. The issue that has gotten the most attention thus far really is the fact that you have banks like Wells Fargo and JP Morgan Chase that are either invested in private prison companies or that help provide private prison companies with credit so that they can actually build the facilities. You have a lot of the private prison companies — in order to be able to build the prisons, the immigrant detention centers that they are making — they rely on lines of credit from banks like Wells Fargo and JP Morgan Chase.

One of the other issues that has actually been less reported on is that there is also a big link between municipal bonds and private prisons. Even when you have private prisons, in many cases the way the counties actually build the facilities [is] by issuing municipal bonds. Those bonds are underwritten by banks. One of the things that has happened in several places is that you had underwriters at banks that wanted to sell these bonds that went around to cash-strapped counties, really pitching them on private prisons as a way to attract federal dollars: “If you build this prison, you can fill it with inmates from the federal system. The federal government will pay you to have this facility within your county. If you issue a bond, you can build the prison, you can then contract it out with the CCA or GEO Group, and based on the revenues you get from the federal government, you can pay back the bond and you will have extra money left over to fill your budget hole.”

In many cases, the [prisoners] didn’t actually materialize because over the course of the last 10 years, prior to the Trump administration coming in, there actually was a move away from mass incarceration. Not on a big level, but certainly on a level that the trends were looking downward and a lot of the private prison companies were really in trouble…. Counties that had taken out these private prison bonds … in many cases they defaulted on those bonds. It affected their credit ratings and then [led] to budgetary problems for those counties and so forth. We really want to dig into this issue on private prison bonds and figure out how we can both hold accountable the banks that really pushed counties to take out these bonds, but then also, how do we look at the bonding process as a lever in the broader campaign to try to stop private prisons.

Anything else that you guys are working on that people should know about?

Bhatti: One other area that we are looking to develop over the course of the next year or so is looking at “Who are the individual people that are funding Islamophobia and who are the corporations that are profiting from it?” There has been a lot of great work that has been done by other organizations like the Center for American Progress, the Center for New Community, the Southern Poverty Law Center, identifying some of the foundations and think tanks that are funding attacks on Muslims. We want to dig a little bit deeper and look to see “Who are some of the individual people that fund those foundations that help lead and fund those think tanks and what are the different ways they are profiting from or funding attacks on Muslims and how do we hold those people accountable?”

We suspect that as we actually start looking at identifying who these people are that we will also find that these same people are also bad on a whole host of other issues. We suspect that once we start digging in on these examples, what we will find is that by doing this research, by doing these campaigns, we can also build bridges between the Muslim community and other movements of the left.

How can people keep up with you and your work?

BP-Weeks: You can visit our website at www.acrecampaigns.org. If you are interested, in particular, in the Forgo Wells work, you can go to www.acrecampaigns.org/forgowells, as well. We are also on Twitter and Facebook @acrecampaigns.

Interviews for Resistance is a project of Sarah Jaffe, with assistance from Laura Feuillebois and support from the Nation Institute. It is also available as a podcast on iTunes. Not to be reprinted without permission.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.