Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

Melieni Cruz, who helps prepare the meals passengers eat on airplanes, went thousands of dollars into debt because she couldn’t pay her soaring medical bills. “When the doctor found cysts on my ovaries, I had to save for a year to afford the procedure, and my cysts got bigger and more painful the whole time,” she said as she picketed the terminal at San Francisco International Airport (SFO).

Cruz works for LSG Sky Chefs, and her union, UNITE HERE Local 2, has been trying to renegotiate the contract that covers her and 1,500 other workers. The cost of health care premiums and wages are the big sticking points in bargaining. Medicare for All would certainly take Cruz’s health care costs off the bargaining table, and ensure that she gets treatment without having to endure a year in pain to save enough money for it.

That’s an important reason why Local 2 endorsed Bernie Sanders, who campaigned for Medicare for All long before the current presidential nomination race. Cruz went to work for LSG Sky Chefs for the medical coverage, for which she pays $150 a month on a wage of $18.16/hour. The deductible on the $8,000 surgery she needed put a huge hole in her income, and she’s now afraid to go to the doctor.

Preserving affordable health care was one of the reasons why Local 2 went on strike at the Marriott hotels in San Francisco a year ago. For 61 days, hotel workers mounted picket lines in a strike coordinated with other UNITE HERE locals in nine cities. The union has one of the best health plans of any San Francisco union, paid for by the hotels, and workers struck to keep the hotels from making them pay for it. Fear of losing a similar plan kept Local 2’s sister union in Las Vegas from supporting Sanders and Medicare for All, but many of its members voted for him anyway, knowing that not every worker in Las Vegas enjoys the health care that the casino workers have fought for.

In the airline food kitchens, however, the situation is very different. Roberto Alvarez, a worker who loads food onto planes, says, “I prepare food and beverage for some of the world’s biggest airlines, but I have to go to a free clinic because my company insurance is so expensive that I can’t afford it.”

What’s keeping airline food workers from following in the footsteps of their fellow Local 2 members in the hotels is an antiquated labor law. Candidates on the left side of the Democratic Party have supported some aspects of labor law reform that would make it easier to form unions. But the airline food workers’ situation highlights the need for a further reform that has yet to make it onto the stage in the Democratic candidate debates.

Hotel workers in Local 2 and a handful of its sister unions around the country used a multicity strike to put pressure on the Marriott hotel chain — the world’s largest hotel operator by far. Hotel workers are covered by the National Labor Relations Act. Under that law, striking can still be dangerous for workers, who risk being replaced by strikebreakers. But at least they can strike.

Effectively, Cruz, Alvarez, and the kitchen and catering workers in the airports cannot. Last June they took votes to strike in multiple cities. In San Francisco, 99 percent of the nearly 1,600 workers backed a resolution to act for better conditions. But the Railway Labor Act keeps them from using the tactic hotel workers found so effective.

In order to shut down the U.S. economy, workers must stop goods and people from moving. That’s a basic lesson in this country they learned the hard way on the railroads, in the years when the modern labor movement was born over a century and a half ago. Today airports fulfill the same function railroad stations did a century and more ago. A national job action in airports could bring transportation to a halt, much as strikes on the railroads did over a century ago. The Railway Labor Act was structured to keep both from happening.

To see how this repressive stranglehold was created, we have to go back to 1877, when Congress ended Reconstruction, withdrawing troops from the South that had protected the political enfranchisement of Black people following the Civil War. That same year the Great Railway Strike broke out in West Virginia. From Pennsylvania to Illinois, furious impoverished strikers burned roundhouses and railway cars. Troops — no longer protecting Black voting rights — were sent instead to put down what the government and the railroad barons feared was a worker insurrection.

One striking worker told the newspapers, “I had might as well die by the bullet as to starve to death by inches.”

A quarter century later, workers again tried to cut the railroads’ steel arteries. Eugene Debs organized the American Railway Union and led a quarter of a million workers in 27 states in one of the bitterest strikes in labor history. Once again, the Federal government called in the U.S. Army, broke the strike, and sent Debs to prison, where he became a socialist and war resister.

Despite violent repression, that long strike movement eventually forced Congress in 1916 to grant railroad workers a decades-old demand: the eight-hour day. When railroad workers won it, others demanded and won it too.

But as World War I unfolded, Debs — railing against the war — was sent to prison again, declaring, “While there is a lower class, I am in it, and while there is a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.” As Debs sat behind bars, President Woodrow Wilson and Congress created a Railroad Labor Board, which then cut wages. Railroad workers began another national strike; the Board declared it illegal, and the Department of Justice carried out the board’s prohibition.

Then Congress passed the Railway Labor Act, to make sure that never happened again. The law’s overt purpose was to make it virtually impossible for railroad workers to go on strike, by setting up an arbitration process under a National Mediation Board, which could last almost indefinitely. Unions were prohibited from taking job action before they’d exhausted its interminable steps. And as air travel became common, in 1936 Congress put the workers in the airline industry under the Act as well.

Today, this history of repression traps workers far from the cabs of locomotives or the cockpits of airplanes, but with effects as devastating in their way as the predicament described by the striker almost 150 years ago.

In an earlier era, transportation workers faced violence, but at least they could take action against the robber barons who directly employed them. Today, the airlines are not only protected by the Railway Labor Act, but by the fact that they long ago contracted out their meal preparation. They control the income of workers by negotiating the price of meals they pay to the kitchen companies, but the airlines are not the workers’ legal employer. In response to February’s demonstration, American Airlines in fact claimed, “We are not in a position to control the outcome of their negotiations or dictate what wages or benefits are agreed upon between the catering companies and their employees.”

To the union, this is a legal fiction. One important provision of the Protecting the Right to Organize Act — the labor law reform that Democrats passed in the House of Representatives this year — is to limit the ability of corporations to contract out various aspects of their work. It would also prevent the permanent replacement of strikers. But of course, in order to benefit from this proposal if it passes, first workers in the airport kitchens have to win the right to strike itself.

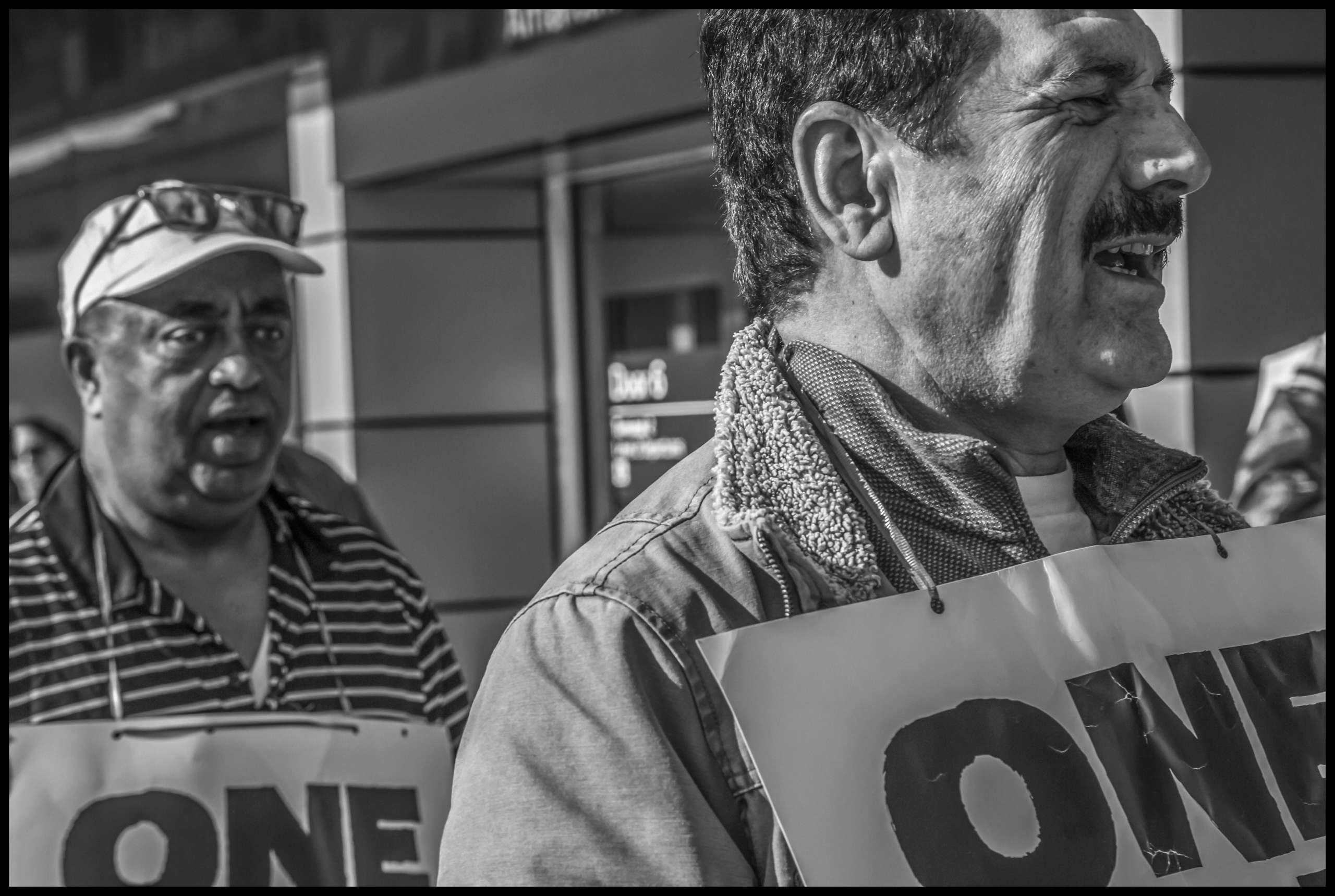

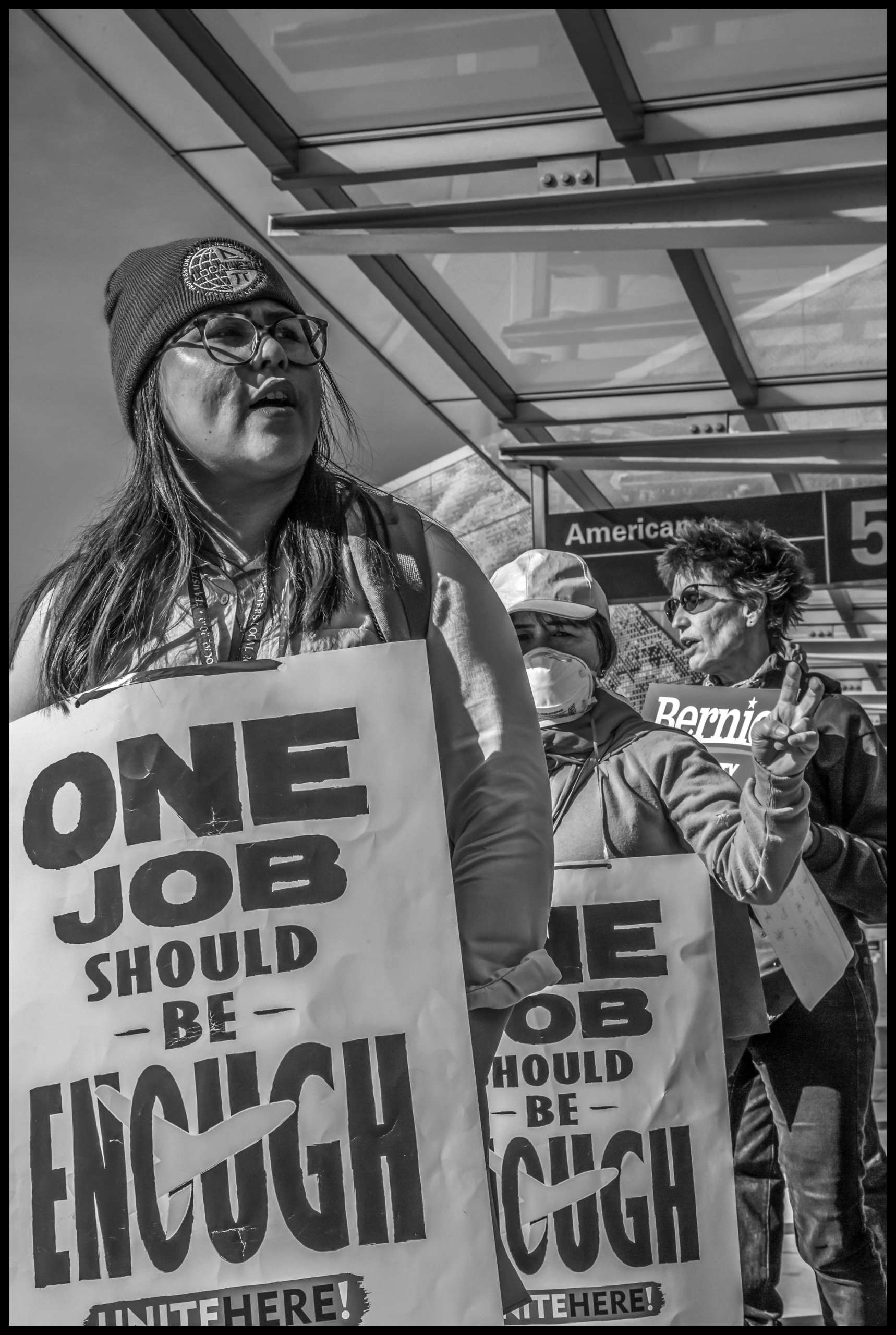

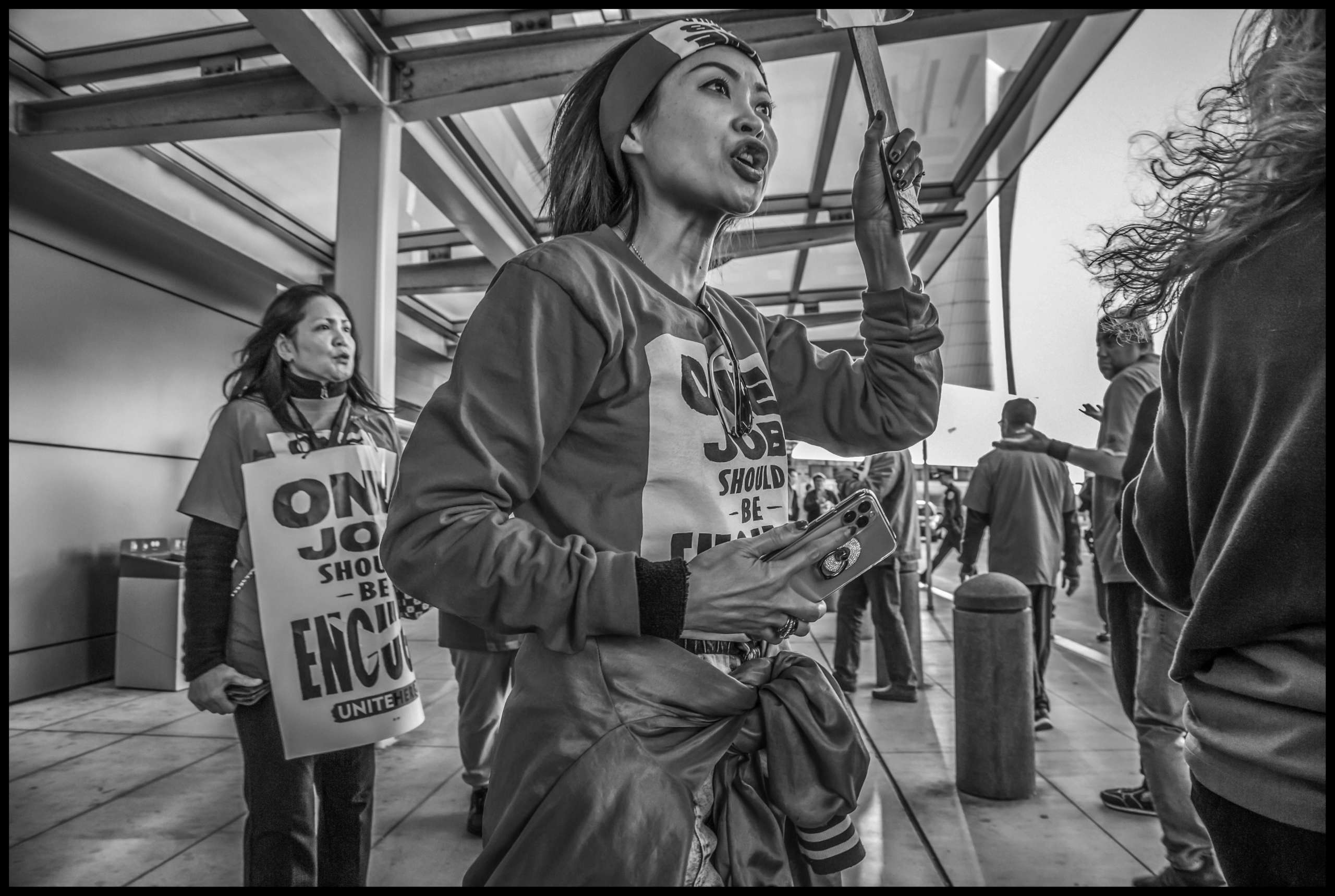

To keep pressure on LSG Sky Chefs and the other main food supplier, Gate Gourmet, workers have picketed the American Airlines terminal periodically and organized sit-ins inside the soaring lobby. In mid-February, airport workers conducted a die-in, lying down inside the terminal while passengers steered their wheelie bags around them.

At the same time as that group of workers lay down inside the terminal, another group of workers walked into the road outside the terminal. Police stopped the stream of cars intent on dropping off passengers, and for half an hour, the union’s activists sat singing and chanting on the asphalt as cops arrested each one.

This was a calm action, despite the evident frustration of would-be flyers. But it brought back memories of less diplomatic confrontations during earlier airport strikes. In 1989, Eastern Airlines pilots struck, and at the San Francisco airport activists stalled clunker vehicles in the terminal roadway, slashing their tires so they couldn’t be easily moved. Traffic soon backed up and stopped the freeway — an experience that neither airport law enforcement and police nor the airport workers themselves have forgotten.

But today, the level of frustration among workers and their union is growing. The denial of their right to strike will inevitably lead to further, and possibly more confrontational actions. Other airport workers will likely support them. This February many not only watched with obvious self-interest as the roadway was blocked, but also picketed alongside the kitchen workers. A group of pilots in uniform, some doubtless old enough to remember Eastern Airlines, joined the food service workers as well.

Airports are vulnerable. And they are as big a factor in the economy today as the railroads were when the Railway Labor Act was passed. SFO alone produced $10.7 billion in revenue in 2018 and employs 46,000 people. American Airlines, which pays Sky Chefs and Gate Gourmet, and determines what the food workers earn, made $1.9 billion in profit last year.

Yet less than half of the workers at Sky Chefs and Gate Gourmet have employer-provided health insurance, and only 10 percent have health coverage for their families.

“My health care is so unaffordable that I avoid important medical tests because I can’t afford the bills,” charged Local 2 member Linda Fajardo. “I work 12 hours a day just to make ends meet. American Airlines is rich enough to make sure that I can see the doctor and have a decent life.”

Local 2’s president, Anand Singh, was among those arrested in the street outside the terminal. He warned, “One job should be enough for the workers who cater American Airlines flights, and we’re ready to do whatever it takes to make that happen.” The National Mediation Board, whose members are appointed by the president, could seemingly care less.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.