Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

Visions in Black and White –

Images from Indigenous Australia

Redfern Community Centre, Sydney

Until June 24, 2013.

www.headon.com.au

“Ngurragah,” says Barbara McGrady, and smiles. The word, pronounced “nuh-ruh-gah”, is one of her favourite utterances. But this committed activist and community photographer won’t be using it to describe her latest exhibition, being held as part of Head On, the second largest photography festival in the world.

“Ngurragah is a Kamilaroi word,” she says. “It’s got a lot of meanings, but basically the way I use it is ‘a bit silly’. It means ‘not too good’, ‘a bit hopeless’, all that.”

And that’s the polite translation?

“Yeah,” she laughs. “But it’s a great word – and I use it a lot.”

However, the word was used at the opening of her exhibition at the Block in Redfern, when she got up to speak. As she walked nervously to the lectern, her nephew Gameroy Newman, who was there to recite poetry and play yidaki, barked out: “Come on, Aunty Ngurragah!”

She laughs at the memory. “That’s his little name for me,” she says. “He’s got a way with words. He’s been all around the world, doing what he does. He’s got a funny sense of humour.” There is a pause. “A weird sense of humour.”

Also displaying a notorious sense of humour at the opening was McGrady’s old mate, Gary Foley. The activist, historian and co-founder of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy had flown up from Melbourne to open McGrady’s exhibition, titled Visions in Black and White – Images from Indigenous Australia.

Foley, who is not readily given to compliments, told the audience: “It’s a measure of my respect for Barbara that I got on not only one plane today to come and open this exhibition – at my age, folks! – but will also be getting on another plane to go back – two in one day!”

Foley noted that although he had just completed a 100,000-word thesis to finally complete his doctorate, “a picture is worth a thousand words”. In that respect, he said, McGrady’s work was far more important than his. He concluded that she was a “National Living Treasure”, a compliment that McGrady takes with a large pinch of salt.

“We’ve got sort of a similar sense of humour,” she says. “I think the whole Australian National Treasure thing is a bit of a hoot. Dame Nellie Melba, Dawn Fraser – they were so racist. And Joan Sutherland, people like that, you know, awful people. They think like Pauline Hanson.”

Foley was also at pains to point out: “I haven’t come to open this just because I’m featured in the exhibition, folks – no, no.”

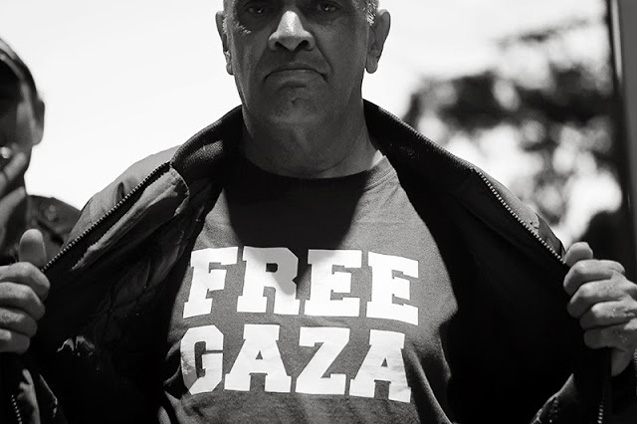

McGrady’s photo of Foley, opening his trademark black bomber jacket to reveal a T-shirt emblazoned with the words “FREE GAZA”, is one of a few of McGrady’s favourites from the exhibition that she has selected to talk about for this article. The photo was taken at another event for which Foley flew up to Sydney at the end of last year.

“The one I took of him in that shirt was at the Boomalli Aboriginal Art Gallery’s 25th anniversary,” says McGrady. “He came up to open it.”

The image of an Aboriginal activist reaching out to Palestinians brings to mind a line from Australian comedian Steve Hughes: “Australians and Israelis get on like a Palestinian house on fire. We both live illegally on occupied land that belongs to other people. Personally I reckon Israel should come to Australia, we’ve got tons of room. The weather’s the same, we’ve got a right-wing government and oppressed Indigenous people. I reckon they’ll slot right fucking in. We’d call it Israelia. We’d have a new passport, kangaroo on one side, Star of David on the other. Of course, now it’d be the Star of Davo…”

McGrady smiles. “It’s exactly the same thing,” she says. Yet sometimes it seems the Middle East gets more attention in Australia than Aboriginal affairs do. “Yeah well, you know, we’re just the Aboriginal problem,” says McGrady, then she laughs long and hard. “That’s all. We’re nothing special. We’re always here.”

The event at which McGrady took Foley’s photo was not the first time he had visited Boomalli Aboriginal Art Gallery that year. He also opened McGrady’s previous exhibition there – a collection of protest and performance pictures titled Rites Here! Right Now!

At that opening, Foley noted that although there were many community photographers in Australia, McGrady’s photos were rare and important because “they were taken with the Aboriginal eye”.

McGrady agrees. “No one, it doesn’t matter how good a photographer they are, nobody has my eye,” she says.

It might also be said that nobody has McGrady’s eyes. They are the most striking thing on meeting her in the flesh – glittering orbs of opalescence that seemingly no camera can capture. A modest woman, McGrady won’t like that description, and will probably laugh at it. An SBS television report on her new exhibition described her as “quietly spoken”. But today, sitting in her favourite cafe in Glebe – the bohemian inner-city Sydney enclave where she has lived since the 1970s – she is strong in voice and long in laughter.

I have known McGrady for a few years. She has been surprisingly friendly to me, a recent immigrant from Britain, the nation that colonised her country and brutalised her people. She even calls me “a mate”, which still takes me aback.

“I know people that turn the other way,” she says. “But you won’t learn anything if you don’t put yourself out there and open yourself up to different people and the way they think and the way they operate. We all like to stick to what we know and we’re all comfortable with what and who we know. We’re all tribal, in a way.

“I’m no different, but because I have been forced from a young age to live a dual life, to live and operate in a white, Anglo-Saxon world, I had to learn to co-exist. There was no other option. That forces you to look at the world around you and how people operate. You’ve got no choice but to, unless you want to go and live on your desert island. And what I say to people is, ‘Because I’m a minority, I was forced to exist in your world and I know your world like the back of my hand, because I had to. But you don’t know anything about my world. I think I’m one step ahead of you.'”

OPEN MIND, OPEN EYES

It was McGrady’s open-mindedness that opened her eyes to photography and fired her passion for pictures when she was growing up in far north-west New South Wales, on the border with Queensland.

“I grew up reading really unusual material for a kid in a rural, country, redneck town,” she says. “I grew up on a property – on and off – where my father and brothers worked for a big, wealthy landowner called John Bucknall in Wongee. My father was one of the ‘station blacks’ and my brothers worked there too as they grew up. Because my father was a reader, Mr Bucknall used to give him magazines like Time, Life, Paris Review, Punch, Esquire, Playboy. I remember reading Esquire and Playboy because my parents let me read them as a kid.”

She laughs.

“And do you know what I loved about them? They were the only publications that had black writers in the Fifties, Sixties. There were people like James Baldwin; Alex Haley, the guy that wrote Roots; Langston Hughes, one of my favourite poets; a black woman anthropologist called Zora Neale Hurston – there were all these incredible people. I mean, where else could you read about people like Malcolm X? Nowhere. That was my reading material as a kid. That’s how I learnt to read. So that’s how I became interested in the world around me and in photography, because some of the images in Life magazine were just incredible – and images of black sportsmen and women – that’s where I got all that from.”

If she could put any of her passions on a podium, it would be sport. The former school sports captain has learnt how to hold her own in the scrum of snappers at big matches.

“Some of the international guys are a bit of a pain – they’d climb over the backs of their grandmothers to get a shot,” says McGrady, who has five grandchildren. “I suppose I’m a little bit of an oddity, being a lot older than them, being a woman, and being black. There’s also the young ones that are brash, they’re pushy and they’re cheeky. They don’t give you the space to move. They’ll push you out of the way. They’ll overrun you if you let ’em, but I don’t. I just say, ‘YOU get out of MY WAY.’

“You know what my current bugbear is? Recent immigrants to this country who have taken on the racist ideology. I get it all time from security guards, who just think I’m trying to get into a place to crash, or whatever. I pull them up and tell them, ‘Do you know you’re in a black country?’ Then I pull out my media pass.”

That passion for her people and sport is reflected in the cover image for her exhibition flyer – a shot she took of world champion Aboriginal boxer Anthony “Choc” Mundine.

“I’ve been a fan of his for a long time and also his father, Tony,” says McGrady, who photographed Mundine at the gym his father runs in the Block. “Choc’s people just rang me. They said, ‘we’re doing sparring, come on down’. As soon as I snapped it I knew it was a ‘money shot’. And when I actually saw it on the computer, I knew I’d captured a special moment. A pretty powerful image. I think it says a lot about him as an Indigenous sportsman and as a person.”

The image shows Mundine battered, exhausted and on the ropes, which says a lot about his public life. The outspoken athlete and sometime radical rapper is pilloried by the press for saying the exact same things that some of their more critical colleagues are praised for. The way Mundine is mauled by the media brings to mind a line from radical Scottish-Jamaican rapper Akala:

Pilger can say it, so can Naomi Klein

It’s free speech for them, that’s fine

Young black rappers should utter the same words

Utterly absurd, nutter, insane, nerd

“Yeah, or ‘they’re just whingeing’,” says McGrady, laughing. “You know, ‘we need to get over it’. But when someone whose integrity and credibility is right up there, someone like John Pilger, people take notice, and so they should.

“I think Choc’s a little bit different because he is promoting his boxing tournament and himself, as a boxer, as a fighter, and there’s a lot of different layers to what he says when he’s asked for a quote or when he’s promoting his next fight, because he does do the boxing hype thing very well. But there’s also a lot of truth in what he says.”

TRAINED AS A NURSE

McGrady’s passion for the physical led her to train as a nurse in a small Queensland town in her youth. It’s a time she recalls with humour and horror.

“I grew up being someone who was not really big on birthdays,” she says. “But my workmates at the hospital decided to throw me a 21st birthday party and the funny part was, there was no black people there.” She cracks up laughing. “It was all mainly for their benefit. It was ngurragah.”

She is passing on her passion for pictures – not nursing – to her five-year-old granddaughter Alkira, who seems to follow McGrady everywhere.

“She’s a little budding photographer,” says McGrady. “She’s the eldest one. She knows everything. She thinks she’s 21. She’s very precocious. She was living in Tamworth with her mother, but she’s down here for a while with me. We’ve got a special bond. She’s very talented, she’s a dancer and she’s a real performer.”

McGrady’s stunning shot of Alkira is one of her favourites from the exhibition.

“We were at Darling Harbour and as we were walking along there was this wall of water, like a waterfall. She just ran through it. I yelled out, she turned around and I just snapped her. I really like that one.”

But photographing Indigenous subjects that are less personal can prove more problematic.

“A few people have said to me – non-Aboriginal photographers – ‘Ah, you’ve got it easy, you can just stroll in there and go bang, bang, bang, bang’,” says McGrady. “And I’ve said, ‘No, I don’t have it easy. It might seem that way to you, but I don’t.’ They think it’s great for me, they think I’ve got a foothold: ‘Ah yeah, we don’t get to do that. We have to ask permission, we have to do this, we have to do that.’ I say, ‘Well, I have to, too. I don’t just barge in there and go bang, bang, bang, you know. They’d soon tell me.'”

Maori academic Linda Tuhiwai Smith says: “What is frustrating for some indigenous researchers is that, even when their own communities have access to an indigenous researcher, they will select or prefer a non-indigenous researcher over an indigenous researcher… indigenous researchers work within a set of ‘insider’ dynamics and it takes considerable sensitivity, skill, maturity, experience and knowledge to work these issues through.'”

McGrady is no fan of anthropologists, noting that Australian Aboriginal people are the most researched people in the world. But she says it can be easier for non-Indigenous people to do that work.

“It is a lot easier because they do their research and they say, ‘well, I’ve found this out’ – and that’s it for them. Whereas for me, when I do research, I can say, ‘no, that’s not right’, or ‘it’s not like that’ or ‘that’s not my experience’, ‘I don’t see it that way’.”

However, she can have an advantage in such situations.

READING THE SIGNS

“If I see another Indigenous person on the street, I won’t know who they are, they’re probably from another area, they could be Murri, Koori, Nunga, Nyoongar, Yamatji, whatever. But if I see them and they see me, we have a connection. And they could be from a really diverse cultural background, but we’ll always have that connection and I’ll always know them, not personally, but I’ll KNOW them and I’ll know who and what they are, just because they’re Indigenous or Aboriginal. There’s all kinds of signals that signify to me who or what they are. From where I come from, we do this thing where that means ‘hey’, ‘hi’.”

She holds her palm flat, face down and sweeping out from the body.

“You don’t have to say a word, you just walk past someone and go…” She does it again. “…and they’ll know.”

However, McGrady’s degree in sociology means she is fascinated by meeting people from other backgrounds – even those that have eluded her for years. It is why she went to Sydney’s world famous Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras for the first time only this year. It resulted in another of her favourite photos from the exhibition.

“It was just really amazing,” she says. “All these people in their finery, all their beautiful costumes. They were just deadly, you know? The blokes were pretty spectacular. I’d always seen it on TV and my friends had shown me their photo shoots and I’d say, ‘oh, yeah’. But it just blew me away. The whole thing was just awesome. I was up there with the First Australians float and I saw these three – well, I call them sister girls. They were just so gorgeous, they were dressed to kill. They were just beautiful. And they saw me and they came over and started posing and styling up.” She laughs. “It was a pity I had to use the black and white shot because in colour they just dazzled.”

The shot recalls a quote from Foley – that the older he gets, the more he is struck by the parallels between racism and sexism. McGrady agrees that homophobia is no different. “Yeah,” she says. “Those three ‘-isms’, they’re all connected. If people looked a bit deeper, they’d see that there is a big connection…”

McGrady is interrupted by a phone call from someone who is accompanying her to the Sydney Film Festival’s opening night that evening. The festival is being opened by the premiere of Mystery Road, a film by McGrady’s cousin, Ivan Sen. McGrady will be down there as usual, snapping away.

“I’m feeling a bit crook – what time are we meeting,” she says into her mobile. “I like to get there early and get a prime spot on the red carpet where we won’t be elbowed out of the way.” Then she doubles up laughing.

When she finally hangs up, she turns to me and says: “I’m very proud of Ivan and what he’s done. His grandmother was my mother’s niece. He’s a really good photographer, too.”

I suggest we finish up by taking a slow exposure photograph of McGrady out on the street, for the article. McGrady says she isn’t feeling too well, that she has just come from the chemist. She points to a sore on her lip. We agree that the photo is not really needed, that I can use others I have taken that she has used herself.

But as with all subjects, there’s another angle to that. Like many photographers, McGrady doesn’t particularly enjoy being photographed. When people post photos of her to Facebook, McGrady – the photographer who takes pictures worth a thousand words – usually responds with just one word: “Ngurragah.”

Below is the full, unedited Q&A with Barbara McGrady, in which she also talks about the feedback she got about her exhibition from fellow photographers…

***

I wanted to talk to you about some of your favourite shots from the exhibition. Tell us about the one you chose as the cover for the flyer, of world champion Aboriginal boxer Anthony “Choc” Mundine exhausted and against the ropes.

I’ve been a fan of his for a long time and also his father, Tony.

Was it Tony, who runs the gym in the Block in Redfern, that invited you down?

Other people invited me down, Choc’s people. They just rang me and invited me down, said we’re doing sparring, come on down. Yeah, I like that one. That one seems to have captured a lot of people’s imagination or something, they seem to like that one.

Well he’s always on the ropes isn’t he?

Ah, yeah I suppose so, metaphorically speaking.

The way Mundine is mauled by the media brings to mind a line from radical Scottish-Jamaican rapper Akala:

Pilger can say it, so can Naomi Klein

It’s free speech for them, that’s fine

Young black rappers should utter the same words

Utterly absurd, nutter, insane, nerd

Yeah, or they’re just whingeing. You know, we need to get over it [laughs]. But when someone whose integrity and credibility is right up there, someone like John Pilger, people take notice, and so they should.

But what Mundine says is pretty much the same, but he’s vilified for it.

Well, I think that’s a little bit different because he is promoting his boxing tournament and himself, as a boxer, as a fighter and there’s a lot of layers, different layers to what he says when he’s asked for a quote or when he’s promoting his next fight, you know? Because he does do the boxing hype thing very well but there’s also a lot of truth in what he says. Even though the way he says it doesn’t quite [laughs] fit well with a lot of people. As soon as I snapped it I knew it was a ‘money shot’ – you just get a feel for it. And when I actually saw it on the computer, I knew I’d captured a special moment. A pretty powerful image. I think it says a lot about him as an Indigenous sportsman and as a person, well, for me it does. I see a lot in it that probably a lot of other people wouldn’t see.

Sport is your passion and I believe you’ve learned to hold your own with the mainstream media sports photographers after some ugly incidents.

Well I suppose I’m a little bit of an oddity, being a lot older than them, being a woman, and being black I suppose, I don’t know. There’s the young ones who are brash, they’re pushy and they’re cheeky, they don’t give you the space to move. They’ll push you out of the way. They’ll overrun you if you let ’em, but I don’t. I just say you get out of MY way. They go, oh, OK. But the older guys are great. Some of the international guys are a bit of a pain – they’d climb over the backs of their grandmothers to get a shot.

Tell us about the shot of your granddaughter.

Alkira. She’s a little budding photographer. We were at Darling Harbour and as we were walking along there was this wall of water, you know like a waterfall thing and she just ran through it. I yelled out, she turned around and I just snapped her. Yeah, yeah, I really liked that one. I’ve got five [grandkids] all together. She’s the eldest one. She knows everything. She thinks she’s 21. She’s one of those – very precocious. She was living in Tamworth with her mother, but she’s down here for a while with me. We’ve got a special bond, yeah. She’s very talented, she’s a dancer and she’s a real performer. She does splits, the does cartwheels, she does all the hip-hop dancing. She’s been using my 600 [camera].

And you’ve been showing her the ropes?

Yeah, even though she knows it all [laughs].

Tell us about the shot taken at Sydney’s Mardi Gras.

That was my first ever Mardi Gras shoot. It was just really amazing, all these people in their finery, all their beautiful costumes. They were just deadly, you know? The blokes were pretty spectacular. I’d never been to one before! I’d always seen it on TV and my friends had shown me their photo shoots and I was, ‘oh yeah’. But it just blew me away, the whole thing was just awesome. I saw the First Australians float. they were in a Cadillac, they led the float with the Stonewall people. I was up there with the First Australians float and I saw these three – well, I call them sister girls – ’cause, you know, that’s what they are. They were just so gorgeous, they were dressed to kill. They were just beautiful. And they saw me and they came over and started posing and styling up [laughs]. It was a pity I had to use the black and white shot because in colour they just dazzled.

The shot recalls a quote from your friend, Aboriginal activist and historian Gary Foley, who opened your show – that the older he gets, the more he is struck by the parallels between racism and sexism.

Yeah, well those three -isms, they’re all connected. If people looked a bit deeper, they’d see that there is a big connection.

Tell us about your shot of Foley in his “FREE GAZA” T-shirt.

The one I took of him in that shirt was at the Boomalli Aboriginal gallery 25th anniversary. He came up to open it.

There are many parallels between Gaza and Indigenous Australia, yet sometimes it seems the Middle East gets more attention in Australia than Aboriginal affairs do.

Yeah well, you know, we’re just the Aboriginal problem [laughs long and hard]. That’s all. We’re nothing special. We’re always here.

But it’s the same thing.

It’s exactly the same thing.

It makes me wonder why people focus on what’s overseas, rather than on their own doorstep, but then it’s hypocritical for me to be writing about Aboriginal issues, having immigrated here recently from England.

Well look, that’s plausible because there are always people on the outside looking in, who can see more clearly. And have a better perspective – or a different perspective – than ordinary Australians.

Yes, different, but not better, I reckon. Foley says your work is so important because it’s taken with the “Aboriginal eye”.

Like I said in my SBS interview, no one, it doesn’t matter how good a photographer they are, nobody has my eye. It doesn’t mean I’m better or I do more amazing work than the average photographer. It’s just that it’s my OWN perspective, coming from someone who is a part of the community, someone who knows the community and someone who sees something that outsiders or someone who’s not Indigenous could see. But what I’m trying to say is even another Indigenous photographer would never see what I see, because everyone has their own particular eye and everyone has their own particular way of photographing. It’s unique and it’s multi-layered and very complex when you photograph Indigenous people.

In what ways?

How long have we got? [Laughs] If I see another Indigenous person on the street, I won’t know who they are, they’re probably from another area, they could be Murri, Koori, Nunga, Nyoongar, Yamatji, whatever. But if I see them and they see me, we have a connection. And they could be from a really diverse cultural background, but we’ll always have that connection and I’ll always know them, not personally, but I’ll KNOW them and I’ll know who and what they are, just because they’re Indigenous or Aboriginal. There’s all kinds of signals, symbiotic things, that signify to me who or what they are. From where I come from, we do this thing where that [palm flat, face down and sweeping out from the body] means ‘hey’, ‘hi’. You don’t have to say a word, you just walk past someone and go [does it again] and they’ll know. That’s what I’m trying to get at. It’s like hearing an Archie Roach song and just knowing everything he’s singing about, you KNOW. You might have lived it, you might have experienced it. You just know.

There’s a whole shared experience.

That’s IT. Yeah, yeah. So that’s why it’s very complex.

In Decolonising Methodologies, Maori academic Linda Tuhiwai Smith says her Indigenous students often have trouble ‘researching’ Indigenous people because the students have a lot of cultural weight behind them, there may be clashes with certain people they are researching, or history between their people, and they can end up hurt. She says in that way, it can be easier for whites to ‘research’ Indigenous people.

It is a lot easier because they do their research and they say, well, I’ve found this out – and that’s it for them. Whereas for me, when I do ‘research’, I can say, ‘no, that’s not right’, or ‘it’s not like that’ or ‘that’s not my experience’, ‘I don’t see it that way’.

And you wouldn’t just fly in and fly out – there would be repercussions.

Yeah, you know, there’s a lot to consider. A few people have said to me – non-Aboriginal photographers – ‘ah, you’ve got it easy, you can just stroll in there and go bang, bang, bang, bang’ and I’ve said, ‘no, I don’t have it easy. It might seem that way to you, but I don’t.’ They think it’s great for me, they think I’ve got a foothold, ‘ah yeah, we don’t get to do that. We have to ask permission, we have to do this, we have to do that.’ I say, ‘well, I have to, too. I don’t just barge in there and go bang, bang, bang, you know. They’d soon tell me.’ [Laughs]

We’ve talked before about how even your left-wing white mates don’t see the privilege their white skin affords them, but that’s almost like they’re saying you’ve got black privilege.

Yeah, yeah, black privilege – a great thing isn’t it? Do you want to swap? [laughs] You’re too funny.

Tell us about your shot of activist, presenter and actor Alec Doomadgee, taken at the premiere of the ABC series ‘Redfern Now’ at the Block, where your exhibition is being held. He’s great – he’s what I call a ‘smooth radical’.

He’s a bit of a smooth dude, he’s pretty cool. The curator, Belinda Mason, she chose that one as number one, right near the door, because it’s a strong image, he’s a good-looking guy, he’s known and he’s a cultural man.

And it was taken just metres from where it‘s being exhibited. Tell us about Belinda, the curator.

Belinda Mason is a really, really good, award-winning photographer, who’s been around The Block and knows the mob over there. She’s been around there for about 20 years on and off. So she knows the community, she’s very sensitive to all the Aboriginal issues with photographing Indigenous people. She was a big help to me with curating the show and picking the images and she’s also a friend who I trust. With a curator, you sort of put yourself in their hands and hope that they get it right, and I think she did. I really like the way she presented it all, which was good. It’s funny because I had some award-winning friends and colleagues there [at the opening], like, you know Glenn Lockitch? He did two tours on the Sea Shepherd that toured Antarctica. He does really amazing work and he’s one photographer I really admire. I suppose you could call him an activist photographer because there’s a lot of social conscience, social protest stuff with his work. He’s a really good photographer and someone who I admire, both as a photographer and as a person. I was lucky, he gave me the thumbs-up with my exhibition, which was pretty cool. I care what my friends and colleagues say, more than most people I suppose. [As for] Joe Public, it’s great if they like it, but, you know. Another friend who’s a former Time magazine photographer, Lisa Hogben, she said it was good, she said it was great! Alex Wisser, he’s a funny guy, he’s got big red beard. He used to have a gallery in St Peters, or Tempe, one of those places. It was called Index Gallery. He’s an American photographer, but he’s been over here a few years. He gave his little critique and he liked it, too. Everyone matters, but photographers are different because they see things differently. They have a whole different critique.

You’ve told me you move in a lot of different circles, with people of different classes and political perspectives. I guess you’re fascinated by people.

Yes, I am, yes. I’m a people watcher. I find it all pretty fascinating, because my academic background is I’m a sociologist, so I look at the sociological aspect of it. I find it all really interesting, the way people react and their experience and their perspectives and it’s all really interesting.

People often stick to their own political tribes, but I find people of a different political perspective to mine the most interesting, because they tell me what I’m not already thinking.

They do, they do. People of a different ethnic background I find really interesting, too, because it’s a whole new – or different – perspective from myself. People from another country, even from a different religious background, cultural background, class background, all that’s sociology. It’s all really interesting and you never know, you just never know what you’re going to encounter. So it can be a bit of a mystery. I take people as I find them and sometimes, because of their background or their social standing or social status or class sometimes, they’re the ones that really surprise you. Because they’re so different to you and your experience and how you grew up, they can amaze you sometimes.

You’re very open-minded.

Oh, yeah! Yeah, you have to be. You can’t – you know, what’s the use of having a closed mind?

But if you’re an oppressed minority and you’re up against it you could easily go the other way.

You can, and I know people that have and that do turn the other way. But you won’t learn anything if you don’t put yourself out there and open yourself up to different people and the way they think and the way they operate, you won’t learn anything. We all like to stick to what we know and we’re all comfortable with what and who we know. We’re all tribal, in a way. We have our own – it’s sort of like a footy club – we stick to who and what we know and what we’re comfortable with. I’m no different, but because I have been forced from a young age to live a dual life, to live and operate in a white, Anglo-Saxon world, I had to learn to co-exist. There was no other option. Like at school for example, to socialise and to get along you live in that world, and that forces you to look at the world around you and how people operate, and you’ve got no choice but to, unless you want to go and live on your desert island, because that was the world that I was born into. I had no choice. And what I say to people is, ‘I was forced to exist in your world – because I’m a minority – I was forced to exist in your world and I know your world like the back of my hand, because I had to, but you don’t know anything about my world. I think I’m one step ahead of you.’ [Laughs]

Speaking of living in other worlds, tell us about what happened on your 21st birthday.

Oh, my 21st birthday [laughs]. That was a bit of a hoot. In my younger days I trained as a nurse in Queensland and for my 21st birthday I grew up being someone who was not really big on birthdays. It was just another day and I was a year older and I wasn’t one of those kids who, er, you know, who loved a birthday party. It didn’t really matter to me. But anyway, my workmates at the hospital decided to throw me a 21st birthday party and the funny part was there was no black people there [cracks up laughing]. It was all, mainly, for their benefit. For the token black. It was ngurragah. It was actually. I didn’t really care.

Tell us about the meaning of that word, ngurragah.

Ngurragah is a Kamilaroi word. It’s got a lot of meanings, but basically the way I use it is ‘a bit silly’, it means ‘not too good’, ‘a bit hopeless’, all that, hmmm.

That’s the polite translation?

Hmm, yeah.

And you’ll stop there.

Yeah, I’ll stop there [laughs]. But it’s a great word – and I use it a lot.

The word was used at the opening of your exhibition, when you walked to the lectern to speak. Your nephew Gameroy Newman, who was there to recite poetry and play yidaki, barked out: “Come on, Aunty Ngurragah!”

Yeah [cracks up laughing].

Is that what you’re known as?

No, that’s his little name for me. He’s got a funny sense of humour, weird sense of humour [laughs]. Gameroy is one of the deadliest didge players and dancers you’ll ever meet. He’s got a way with words and he’s a great MC and he really knows how to get the audience in. He’s got a great way of engaging. He’s been all around the world, doing what he does.

Did he also perform at the event you did down in Melbourne, where you took photos of a cultural performance for an Italian family?

Yeah that’s right, the Veneto Club with the Mattioli Brothers… that was a great gig. I really enjoyed that.

I loved the line they came out with in that wonderful accent, as you described it, ‘Ah, the Aborigines are here!’

No, no, they did, honestly! I cracked up! It was cute! They all joined in dancing too. Because Gameroy got them all up, all the old mama mias! [Laughs]

Gameroy’s your nephew, right? So he’s your sister’s …

No, not whitefella way [laughs]. No, we’re not related that way. But because he’s my clan and my subclan group, he’s my nephew. His father was like one of my brothers.

At your opening, Foley called you a ‘National Treasure’.

Oh that was a bit embarrassing, that was a bit cringeworthy.

It wasn’t [laughs]. I think he was serious, though.

Well, we’ve got sort of a similar sense of humour. I think the whole Australian National Treasure thing is a bit of a hoot.

Like mining magnate Clive Palmer.

Yeah! [Laughs]. Dame Nellie Melba, Dawn Fraser, oh my god. I can’t stand her, or Dame Nellie, you know. They were so racist. And Joan Sutherland, people like that, you know, awful people. They think like Pauline Hanson.

And you wonder how many are like that behind their public persona.

Oh look… a lot. But then like I said some people surprise you, exceptions to the rule.

But I can’t fathom how you’d be anti-racist sober then racist when you’re drunk.

Well, they reckon the truth always comes out when you’re drunk, or when you’re angry. Foley and I were talking one day that we’re going to write this book called ‘Some of my best friends are…’ and that’s true, unintentionally or intentionally, it always comes out, the ingrained socialisation of racism always comes out. It doesn’t matter who they are, what they are, how long they’ve known you, it always comes out in them, always. And it’s not surprising. Could be someone you grew up with.

Like in Nelson Mandela’s biography, where he tells how he was alarmed to see that a plane he was flying in had black pilots – he realised the conditioning had even affected him.

Sometimes black people take on the ideology of the conquerors, or the dominant group. You know the deadly doco called When We Were Kings. Remember when they were flying there and [Muhammad] Ali went into the cockpit and he said to the pilots who were black – I don’t know if it was when they were flying to Zimbabwe or when they were flying between countries in Africa – but he was so amazed that the pilots were black. He said, ‘wow, look at this’, you know. ‘We’ve got black pilots!’ [laughs] It was great. I love that doco. It’s funny how we think, black AND white people, how we think about ethnicity and race. I don’t really like the word race, but how else can we explain people’s difference or ‘the other’ as they are termed in anthropological language? We’re all a product of our conditioning and socialisation.

Why don’t you like the word ‘race’?

I dunno. I think if there was another word, I’d use it. I don’t use the word Aboriginal for myself, to identify. I don’t use the word Indigenous. I identify myself from the area I come from, my clan group and my language group and because I’m a woman. So yeah your identity is paramount to who you are. You only have to read anything on Facebook or the internet in general to find out how people think about Aboriginal people in this country, or Indigenous people.

[McGrady takes a call from someone who is going with her in a few hours to the premiere of Mystery Road, the new film by her cousin Ivan Sen]. I’m a bit crook at the moment just the usual. I like to get there early and get a prime spot on the red carpet where we won’t be elbowed out of the way [she doubles up laughing].

Tell us about Ivan Sen – how are you related?

We’re related whitefella way and blackfella way. His grandmother was my mother’s niece. I’m very proud of Ivan and what he’s done. He’s a really good photographer, too. Check out his docos. Like Shifting Sands, Shelter, he’s done heaps, really great docos and short films. And he’s a NICE person. He lives in Hong Kong of all places.

You were looking at the media for your sociology degree, tell us about that.

Can I tell you this? I grew up reading really unusual material for a kid in a rural country redneck town. I grew up on a property, on and off, where my father and brothers worked – a big, wealthy landowner called John Bucknall in Wongee. Anyway, my father was one of the ‘station blacks’ and my brothers worked there too as they grew up. Mr Bucknall used to give my father, because my father was a reader, he’d give him magazines like Time, Life, Paris Review, Punch, Esquire, Playboy. I remember reading Esquire and Playboy because my parents let me read them as a kid [laughs].

But they had serious journalism in them.

Very much so, and you know what I loved about them? They were the only publications that had black writers, in the Fifties, Sixties. And you know there was people like James Baldwin; the guy that wrote Roots, Alex Haley; Langston Hughes, one of my favourite poets, there was all these incredible people. And there was a black woman anthropologist called Zora Neale Hurston who used to write for them too… so that’s how I became interested in the world around me and in photography, because some of the images in Life magazine were just incredible – and images of black sportsmen and women, so that’s where I got all that from. That was my reading material as a kid. That’s how I learnt to read. I mean, where else could you read about people like Malcolm X? Nowhere. Certainly not The Australian, or the Sydney Morning Herald, or The Bulletin, which was one of the most racist publications ever in Australia, oh yeah.

Yeah, I know people that worked for it.

Yeah, I knew some too! [Laughs] ‘Some of my best friends are…?’ Yeah. It’s a funny old world.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we must raise $31,000 in the next 4 days. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.