Truthout is an indispensable resource for activists, movement leaders and workers everywhere. Please make this work possible with a quick donation.

California’s telemetry nurses, who specialize in the electronic monitoring of critically ill patients, normally take care of four patients at once. But ever since the state relaxed California’s mandatory nurse-to-patient ratios in mid-December, Nerissa Black has had to keep track of six.

And these six patients are really sick: Many of them are being treated simultaneously for a stroke and covid-19, or a heart attack and covid. With more patients than usual needing more complex care, Black said she’s worried she’ll miss something or make a mistake.

“We are given 50% more patients and we’re expected to do 50% more things with the same amount of time,” said Black, who has worked at the Henry Mayo Newhall Hospital in Valencia, California, for seven years. “I go home and I feel like I could have done more. I don’t feel like I’m giving the care to my patients like a human being deserves.”

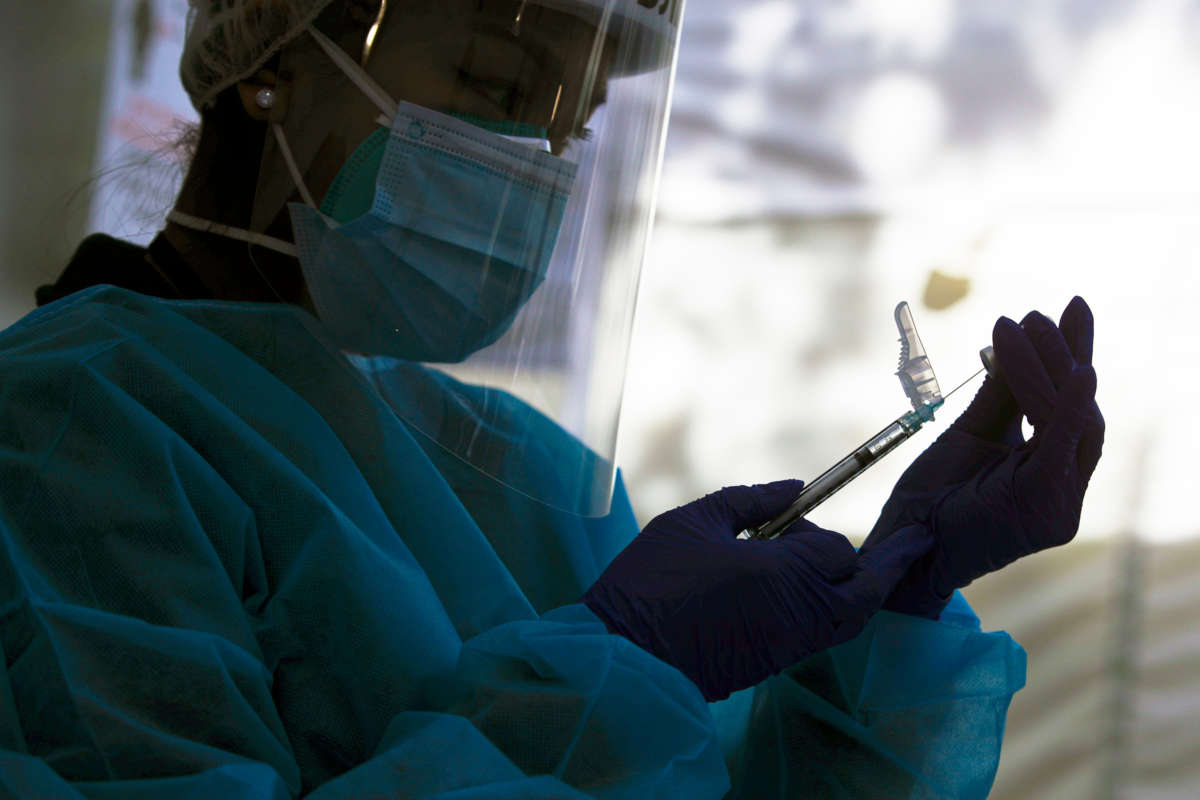

As covid patients continue to flood California emergency rooms, hospitals are increasingly desperate to find enough staffers to care for them all. The state is asking nurses to tend to more patients simultaneously than they typically would, watering down what many nurses and their unions consider their most sacrosanct job protection: a law existing only in California that puts legal restrictions on the nurse-to-patient ratio.

“We need to temporarily — very short-term, temporarily — look a little bit differently in terms of our staffing needs,” said Gov. Gavin Newsom, after he quietly allowed hospitals to adjust their nurse-to-patient ratios on Dec. 11. Usually, California law requires a hospital to first get approval from the state before tinkering with those ratios; Newsom’s move gave hospitals presumptive approval to work outside the ratio rules immediately.

Since then, 188 hospitals, mainly in Southern California, have been operating under the new pandemic ratios: They can require ICU nurses to care for three patients instead of two. Emergency room and telemetry nurses may now be asked to care for six patients instead of four. Medical-surgical nurses are looking after seven patients instead of five.

Nurses have taken to the streets in protest, holding physically distanced demonstrations across the state, shouting and carrying posters that read: “Ratios Save Lives.” The union, the California Nurses Association, says the staffing shortage is a result of bad hospital management, of taking a reactive approach to staffing rather than proactive — laying nurses off over the summer, then not hiring or training enough for winter.

“What we’re seeing in these hospitals is their just-in-time response to a pandemic that they never prepared for — just-in-time staffing, just-in-time resources, not staffing up, calling nurses in on a shift at the very last minute — to boost profits,” said Stephanie Roberson, government relations director for the California Nurses Association. “And we’re seeing how nurses are being stretched even thinner.”

But hospitals say this is an unprecedented crisis that has spiraled beyond their control. In the current surge, four times as many Californians are testing positive for the coronavirus compared with the summer’s peak. As many as 7,000 new patients could soon be coming to California hospitals every day, according to Carmela Coyle, who heads the California Hospital Association.

“This is catastrophic and we cannot dodge this math,” she said. “We are simply out of nurses, out of doctors, out of respiratory therapists.”

The state has asked the federal government for staff, including 200 medical personnel from the Department of Defense, and it’s tried to reactivate the California Health Corps, an initiative to recruit retired health workers to come back to work. But that has yielded few people with the qualifications needed to care for hospitalized covid patients.

Hiring contract nurses from temporary staffing agencies or other states is all but impossible right now, Coyle said.

“Because California surged early during the summer and other parts of the United States then surged afterward,” she said, “those travel nurses are taken.“

The next step for hospitals is to try “team nursing,” Coyle said — pulling nurses from other departments, like the operating room, for example, and partnering them with experienced critical care nurses to help care for covid patients.

Joanne Spetz, an economics professor who studies health care workforce issues at the University of California-San Francisco, said hospitals should have started training nurses for team care over the summer, in anticipation of a winter surge, but they didn’t, either because of costs — hospitals lost a lot of revenue from canceled elective surgeries that could have paid for that training — or because of excessive optimism.

“California was doing so well,” she said. “It was easy for all of us to believe that we kind of got it under control, and I think there was a lot of belief that we would be able to maintain that.”

The California Nurses Association has good reason to be defensive regarding the integrity of the patient-ratio law, Spetz said. It took 10 years of lobbying and activism before the bill passed the state legislature in 1999, then several more years to overcome multiple court challenges, including one from then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

“I’m always kicking their butt, that’s why they don’t like me,” Schwarzenegger famously said of nurses, drawing broad ire from the nurses union and its allies.

Nurses prevailed in the court of public opinion and in law; rules that put a legal cap on the number of patients per nurse finally took effect in 2004. But the long battle made nurses fiercely protective of their win. They’ve even accused hospitals of using the pandemic to try to roll back ratios for good.

“This is the exercise of disaster capitalism at its finest, where [hospital administrators] are completely maximizing their opportunity to take advantage of this crisis,” Roberson said.

Hospitals deny they want to change the ratio law permanently, and Spetz said it’s unlikely they’d succeed if they tried. The public can see that nurses are overworked and burned out by the pandemic, she said, so there would be little support for cutting back their job protections once it’s over.

“To go in and say, ‘Oh, you clearly did so well without ratios when we let you waive them, so let’s just eliminate them entirely,’ I think, would be just adding insult to moral injury,” Spetz said.

This story is from a reporting partnership that includes KQED, NPR and KHN. It can be republished for free.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout’s fundraiser ended last night, and we fell just short of our goal. But your support still matters immensely. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your help.