Part of the Series

Ladydrawers

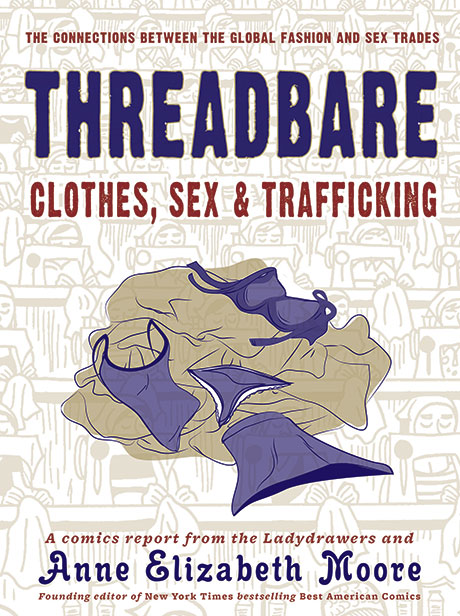

For more than five years, Anne Elizabeth Moore and the Ladydrawers Collective have been creating incisive comics that probe at the intersections of gender and labor. Their just-released book, Threadbare, combines art, storytelling, consciousness-building and old-fashioned muckraking to expose the connections between the fashion industry and the sex trade around the world. I caught up with Anne Elizabeth Moore to find out more about the politics of garment work, the criminalization of sex work, the shady dealings of anti-trafficking organizations and the hope of someday abolishing the “fast fashion” industry for good.

Maya Schenwar: Threadbare takes on the fashion industry in a vivid and personal form, addressing lots of different facets of that industry through interviews with the people employed within it. How did you and the Ladydrawers Collective decide you wanted to take on this topic and — given the multi-facetedness of the focus you’ve cultivated — how did you determine what “this topic” was?

Anne Elizabeth Moore: When we started doing the [Ladydrawers] series for Truthout, I was pretty sure there would be a connection between the global sex and garment trades, but I didn’t actually know what it was. I’d been reporting on the garment factories for a few years at that point, so my gut instincts had been honed, but I hadn’t yet found the links between the two labor arenas. So I said there was one and just hoped, every month, that I could get closer to it.

How Ladydrawers works is, someone proposes a project and then folks get on board with what they want to do for it, and the proposer sort of manages things and makes sure they get done. So the Truthout series has been great, because I can kind of rethink some of the ways I’ve talked about stuff in my text reporting elsewhere and present slightly more complicated ideas in comics, with the help of whoever wants to jump in. So this project was led by me and my interests, for sure, and then when I had a batch of scripts I started approaching the comics creators for illustration work. Some were excited right away, and others were more like, “I’m not sure how I feel about this but oooooh-kaaaaayyy.” Melissa Mendes, who I’ve gone on to work with on a lot of stuff and is one of my closest collaborators, was basically like, “Got it.” Sometimes it seems like she understands projects we work on together better than I do.

As the strips that are now collected into Threadbare started to come together — comics that describe the links between the sex and garment trades, largely through anti-trafficking NGOs — the series became very exciting. That’s when it became clear we were onto something new, presenting new sides of an issue folks have heard about a ton before, but never like this. Like, there’s nothing more tired than complaints about the garment trade. But push those complaints into well argued and illustrated research that indicates the garment trade is a major — if not the most significant — contributor to the global gender wage gap? Then you’ve done something interesting. I think we really felt that, too, as we were working on this stuff. It became very thrilling, even though the process of comics journalism, and working in collaboration, can be really exhausting.

What is “fast fashion”? How does this phenomenon affect Truthout readers — that is, the people reading this interview?

Fast fashion, based on the premise of fast food, is this idea that there should be readily available, cheaply made garments on hand for all occasions that look cute but aren’t intended to last. Truthout readers — and they’ve told me this at events or in emails or on social media — tend to think that by not shopping at H&M or Walmart, they’re not participating in fast fashion, but what Threadbare shows is that the changes in the fashion industry have affected all aspects of warehousing, distribution, clothing resale, waste management and even modeling. Not to mention changes to the textile industry from which clothes are made. So, what we see is that the problems aren’t limited to folks who shop at fast-fashion retail stores like H&M; it’s really changed the entire clothing industry, and no one involved in it can claim it’s for the better.

When we think of who’s exploited by the garment industry, our minds often jump to people (generally, women) working in factories, but in Threadbare, we see this process of exploitation and disposability playing out at lots of different levels — it starts in factories, maybe, but they’re certainly not the end of the “line.” Can you talk about some of the major issues you encountered at various points in the production line, and how they intersect with gender?

Although I had known for awhile that models and warehouse workers faced similar challenges to women in garment factories, when I started talking to those folks, I was shocked by how similar the problems really are. We’re talking about close surveillance of women employees; rampant physical and sexual abuse; little regard for the needs of those raising children; chronic underpayment, late payment or withheld payments; no respect for breaks or meal times; and few advancement opportunities. And these are both very, very physically demanding jobs.

Although what personally affected me was realizing how messy and exploitive the thrift industry end of the garment trade was — I mean, I’m a punk, I’ve always thrifted — what really got me was hearing how consistently poorly the garment trade, at all stages of production, treats women workers, despite the fact that they make up the majority of its workforce…. The garment industry, the largest employer of women worldwide, was clearly created to exploit and abuse women’s labor.

When I’ve talked about this book with people, I mention that it examines the intersections and interactions of the garment industry and the sex trade, and they assume it’s an “anti-trafficking” treatise. Your reporting on the sex trade is more complex than that, and you show how it is tied to clothing production in ways we might not expect. Can you say a little bit about those links between the garment and sex trades?

Well, it is complicated, because these are complicated issues. And I am definitely not “pro-trafficking,” so it’s hard for folks to grasp that, if we reduce global concerns [about] women’s labor to questions of trafficking — which the US State Department and many, many NGOs and not-for-profits would like us to — we overlook the much bigger and more profound picture of corporate abuse undertaken by garment producers that affects the majority of women around the world.

The through line of Threadbare is that, due to a combination of US trade policies with developing nations around the world and cultural restrictions on women working outside the home, the garment industry is the only legal job available to the majority of women in the world. But women are resilient, and so when there are no other legal job opportunities — and the reasons not to work in the garment trade run far deeper than crap pay, long hours, and dangerous working conditions, since sexual assault rates are pretty high in almost any situation where women’s participation is coerced to begin with — women will do what they can to get by on their own, or to feed their kids or whatever. So, where the garment trade exists, there is generally a healthy sex trade as well, and it’s often tolerated or legal until the US steps in and criminalizes it, often as a rider in trade deals. These are presented as “anti-trafficking” measures, because there is a certain mindset that claims that where there is commercial sex there is always exploitation, and all exploitation is pretty much trafficking. (In truth, there are vast distinctions between commercial sex, exploitation, and human trafficking — even outside of the fact that most human trafficking that happens is in non-sexual labor — but if we’re being generous we can see that people are doing what they think is best.)

Anti-trafficking measures, of course, require facilities, and these facilities very often arrest women sex workers and force them into a “rehabilitation” environment where they are trained, often to do the exact same garment manufacturing jobs they probably left to avoid sexual exploitation, after which they are released, back, into the garment trade. These facilities are generally funded by garment manufacturers. To recap: the garment industry supports the arrests of, and finances the supposed rehabilitation of, women who leave the garment trade, forcing them to return to these low-paying, high-risk jobs that more often than not include a likelihood of sexual exploitation. This happens all over the world as a matter of the course of fast fashion.

And I’m supposed to believe that individual bad dudes — no matter how many there may be or how strong their networks — are gathering women up in droves and illegally selling them all over the world, and doing more damage than Nike, H&M, Zara, The Gap, and Walmart combined? Riiiiiight.

What I’m saying is, the whole way that human trafficking is discussed and presented — it’s the latest moral panic, as SWOP [Sex Workers Outreach Project] organizer Serpent Libertine explains in the book — supplants any real address of the systemic, corporate abuse of women workers around the globe. Because the garment industry is one of the primary funders of anti-trafficking initiatives. It’s a closed circle.

Is there any way to “opt out” of fast fashion? What would we have to do to simply not participate in this exploitative industry?

Really, we’d have to abandon all the current laws and international policies that uphold the international garment trade and start over, from scratch. That’s what it will take — there’s no reform of such an unhinged system, the entirety of which rests on taking advantage of women who earn, around the world, only a portion of what men do in the same jobs. Which is also why we must start from scratch: global wage equity is not possible while current international garment and textile trade policies are in place. That will take awhile, and I advocate nothing less than getting started on it right away. I’m tired of all this piddling around.

Obviously, each of us as consumers is not going to revolutionize the fashion universe by changing our habits — so what do you see as a more sustainable and equitable system, when it comes to the garment industry? (Or can that system not really be imagined, exactly, from where we’re standing? Any way you want to answer this question is fine!)

I already sort of answered this question, so how about I just address the fact that since this will take awhile, we will have to be patient and make imperfect choices while we gather the resources to abolish this massive system that keeps women in poverty all over the world. So how do we do that? Well, we have to make considered choices. Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, for example, who likely did more to enfold anti-trafficking measures in trade policies than any other single person, is not going to aid us in this goal, and I would prefer to have a president who will. I will not donate money to your anti-trafficking fun run because, first of all, I likely know the organization the money’s going to, and they don’t offer beds to rescues, so they are fundamentally ineffective — and second of all, “sex trafficking” is not the problem. Poverty is.

It may or may not really matter if I shop at a fast fashion retail outlet, but since I know and care about a lot of the workers that make clothes for certain brands in Cambodia, if I need something I will try to find Cambodian-made goods there. I cannot stress how important it is that they’re not stuck inside the system while it’s crumbling. I thrift from not-for-profit, reputable thrift stores, otherwise — although god’s honest truth I have only purchased three items of clothing since I finished the book. So my purchasing habits have really, really declined.

I’ll continue to field emails from enthusiastic fans and concerned parties around the world, all of whom ask the same basic question: How do we make this system better for real folks? Well, wanting to make it better in a genuine way and not thinking you already know how to make it better is a damn good start. The flood of emails alone makes me hopeful that actually, in my lifetime, I could see this system abolished.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.