Right now is a truly terrifying time for most trans people in the United States. And yet, as has always been the case, trans people continue to take care of each other, affirm each other and create loving communities.

In southern states like Arkansas and Florida, state legislators are moving forward with a direct attack on the rights of trans youth. In more liberal areas of the country, like Massachusetts, a “false sense of security” seems to prevail, according to Tre’Andre Valentine of the Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition. Valentine says that while there are no anti-trans policy moves at the statewide level, there have been plenty of anti-trans attacks at the local level, including parents using anti-LGBTQ rhetoric at school boards.

Organizers in the trans community say this struggle is fundamentally a struggle for bodily autonomy.

Tien Estell, the advocacy and resource coordinator for Intransitive, a community space for trans people in Little Rock, Arkansas, said that although it’s definitely very hard to be trans and queer right now in Arkansas, particularly when mixed with the city’s racism, “the way that we love each other, the way that we show love, and support and enjoy is really, really beautiful.”

Trans People Are Under Attack

An unprecedented wave of anti-trans legislation has been introduced across the United States targeting transgender people and trans youth in particular. These bills range from attacks directly limiting the ability for youth to receive gender-affirming medical care, to punitive measures against parents who support their children, to limits on discussions about gender and sexuality in the curriculum at state and local levels. These limits not only create a chilling environment for LGBTQ+ youth, but also severely limit the ability for youth to have their gender identities — including their correct names and pronouns — respected in an institutional environment.

Estell says that the message of this focus on trans youth is clear: “They do not want trans youth to become trans adults.”

All of the advocates that Truthout spoke with had a similar analysis. The current right-wing attacks are more than just transphobia, and they are more severe even than the earlier wave of anti-trans bathroom bills. They agreed that this is a wave of terror.

Jae Kanella is a community organizer with Rad El Dub Community Land Trust in Lake Worth, Florida, a collective housing project that provides affordable housing for LGBTQ+ organizers and sanctuary for primarily queer migrants. Kanella believes that the wave of legislation at state and local levels is in part the result of groundwork that was laid by the Trump administration. They said that “a lot of the right extremism over the last four years has been allowed to fester, allowed to be granted and celebrated,” and that now these same extremists have been pushed out of positions of power with the change of presidential administration. As recent years have seen more covert right-wing hate groups come out into the open, these right-wing extremists have found a bigger audience for plans that might have once been marginal, Kanella said.

In Arkansas, Estell said that right now “it’s dangerous to be visibly trans.” X Freelon, the executive director of Lucie’s Place, a direct services provider for trans people in Little Rock, Arkansas, pointed out that the anti-trans political project is so radical that the legislators spearheading it are suing the federal government for their right to discriminate. Freelon says, “That’s making an intentional stance saying, if people like this are permitted life and access to life supporting resources, then we will make sure that we stamp that out.”

In other parts of the United States, things are different, but no one describes a safe environment. For example, in Detroit, Nazarina Mwakasege Minaya, senior development associate at the Ruth Ellis Center, which focuses on the needs of LGBTQ+ youth experiencing homelessness, described a sense of “dissonance.” She said this dissonance or whiplash could be especially damaging for young people. As some politicians are the very ones making the center’s work possible, others are the ones threatening to send parents to prison for life for providing their children with life-saving gender-affirming care.

Trans People Are Supporting and Affirming Each Other

Even now as the trans community is under attack, there are groups all over the country, in every state, that are focused on affirming transgender identity and caring for their communities. This community work in many cases includes a mix of direct services, social and psychological support, and mutual aid, as well as other forms of political activity.

Many community groups are working on health care services, whether specifically gender-affirming health care or just general health care. Even prior to the most recent wave of legislation, it was already very hard for trans folks to access the care they need. This is because of the systemic issues that lock trans youth and adults into a cycle of poverty, difficulty securing employment, lack of insurance coverage, and a critical shortage of trans-friendly providers. As a result of the inability to access care and persistent discrimination, transgender people have overall much poorer health than cisgender people.

Becca Moon is the co-founder of Shoals Diversity Center, an LGBTQ-focused center founded in 2017 that grew out of organizing pride events in Florence, Alabama. Moon explained that the center has organized a fundraiser for a pop-up clinic to bring a doctor from Atlanta, Georgia, 250 miles away. This doctor could then begin hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with patients in Florence and continue it via telehealth.

Shoals Diversity Center also offers support groups for transgender people, gender nonconforming people and queer youth. Moon said the center first developed the groups in response to community requests. Support groups are a common and essential service offered by and for the community at many organizations.

One important affirming service that many groups are providing to their communities is space for people to just be themselves. At the Ruth Ellis Center in Detroit, Mwakasege Minaya, described the organization’s drop-in space as a place where trans, gender nonconforming, and LGBTQ+ youth can come in, check their email, get a food box and some new clothes, and take care of any needs. Importantly, Mwakasege Minaya said, in this space, these youth can also “simply be, which is a thing that I think a lot of young people in and outside of the community aren’t really given space to do. Just sort of be.”

At Intransitive in Little Rock, Estell echoed the importance of a space like this for trans adults as well. Going further, Estell highlighted how Intransitive’s space strives to be a welcoming and affirming space of trans joy, where people walk right in the door and exclaim “oh my god, I feel so comfortable here!”

Above and beyond those services — which are critical to trans survival — there are other projects. Intransitive, for example, provides supplies and support for community workshops at its space. These workshops are organized around what people want to offer, and have ranged from soap making to beginner’s lessons on applying makeup. Estell said that creating spaces where “trans folks feel comfortable learning and sharing, that’s a big part of what we do.”

Many organizations share referral lists to trans-owned or trans-friendly businesses and services. This helps community members have a resource list for who is a doctor or lawyer they can trust, wedding or real estate businesses that won’t discriminate, welcoming salons, and other necessary services in areas where trans people may have trouble finding affirming services. The referral lists act as a counterbalance to the chilling effect of anti-trans legislation; these lists work to make trans-affirming services as widely available as possible instead of only available via word of mouth.

Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition (MTPC) extends this idea. One of their newest programs creates a direct link between an employer training program and a leadership training institute for trans people, who will then be matched with businesses or employers who have been through MTPC’s program.

Another ubiquitous and important form of direct service is support with identification documents. Most of the organizations that spoke to Truthout provide some support with getting ID documents to reflect changes to names and gender markers. Some, like MTPC, also offer financial support for this process, which can be costly.

Housing is another major focus of these organizations’ work. According to the National Center for Transgender Equality, due to family rejection and violence, a hugely disproportionate share of the more than 1.6 million homeless youth are transgender or LGBQ-identified. The ultimate goal of Lucie’s Place in Little Rock is to have a shelter that will house 50 people, said Freelon.

Lucie’s Place is currently undergoing a transition from a more traditional shelter with some policies that resulted in significant barriers for trans people, and plans for the new shelter to operate on a collectively run model. In this model, residents are not “considered temporary, transitional people” and make “commitments to be a part of a building or entity that is determined for one another’s safety and protection.” Freelon says that one overall project of Lucie’s Place, both with the shelter and in terms of political advocacy, is about “carving out and creating a space where the community, through intentional investments in itself, engineers housing that is not entitled to anyone, but that is belonging to everyone.”

At the Ruth Ellis Center in Detroit, there are 43 studio and one-bedroom housing units for young adults. The housing also has an ongoing medical partnership so that residents do not need to leave home to go to the doctor, with care based in pediatric and family medicine. Mwakasege Minaya said that the decision-making about the space was initially guided by the advice of young trans women of color on “what would be needed for young people to be safe,” even down to the seemingly smallest details of the architecture. “Everything that the organization does is led by a sort of dialogue,” Mwakasege Minaya said.

Rad El Dub Community Land Trust, in Lake Worth, primarily provides housing. The houses are run on a cooperative model, and one of Rad El Dub’s primary missions is to provide stable, affordable housing to activists and organizers who are then able to participate in a variety of projects, including explicitly trans-affirming groups like the local chapter of Black and Pink, an LGBTQ prison abolitionist organization. Rad El Dub’s vision is one that is broadly intersectional, and focuses on nurturing the social justice ecosystem as a whole.

On the opposite end of the country in Tacoma, Washington, executive director of the Lavender Rights Project Jaelynn Scott said that her organization is trying to build a “place of refuge” focused on Black trans people who may want or need to come to the Seattle area from other parts of the country “for sanctuary.” But she worries that their efforts do “not feel like enough” given the coordinated, decades-long attack on bodily autonomy and the “sophisticated, well-funded strategy” leading these attacks.

The main focus of Lavender Rights Project’s work is doing anti-violence work in the trans community through a Black feminist lens. Scott says that what is most affirming about the organization’s work is that “there’s no white saviorism happening, because there’s no people here to do that.” Since the people in need of the services are the same ones doing the work, Scott highlights that Lavender Rights Project is affirming people’s ability to do the work, creating opportunities for professional development, and also creating more effective service delivery because it is designed by community members.

Anti-violence work is another key area of focus for many of the groups that Truthout spoke with.

Irissa Baxter-Luper is working with the Tulsa Intersectional Care Network, which has mutual aid as its central focus. She said they do a monthly meal train focused on queer people in need and then either bring food to people’s doors or send them some form of grocery gift card. Baxter-Luper says she needed that resource when she moved to Tulsa this year, after a sudden departure from her last job related to her advocacy and mobilization of trans college students around school board issues and bathroom bills. Baxter-Luper says there are other similar small mutual aid hubs in Tulsa, including one just starting called Black Queer Tulsa.

There are fun events too, like drag shows, talent shows, and other performances. But Freelon at Lucie’s Place is careful to distinguish these from a simple politics of visibility. They clarified that these events are about “being permitted to be pleasure seeking without being shamed or denied or punished for doing so” and that this “intentional celebration of transness” cannot be about “escaping political accountability for our community.” The point, for Freelon, is that “liberation is not just physically, it is so much more political than just the ability to be seen and celebrated,” and it will take deeper engagement to achieve that dream as well.

Movement Leaders Are Calling for More Support From the Wider Community

“As a cisgender person I think cisgender people need to think through this dichotomy of ally versus accomplice,” said Baxter-Luper, “and decide who they want to be and where they stand, and put their feet in the work.” She added that funding the work, and trans people directly, is also critical, since they face systemic economic disadvantages.

Freelon, of Lucie’s Place, said the issue of trans rights “never is a single issue in the way that the state is attempting to convince people that it is,” and added that “nobody is in such a privileged position of comfort to ignore things.”

The call for funding was echoed by other organizers. Since being trans, particularly for Black or BIPOC trans people, can result in such economic struggle, organizers say mutual aid funds always need money to provide for a variety of their communities’ needs. This need is compounded by additional costs that accrue to trans people for healthcare, for example, because insurance will not cover certain gender affirming care or because of the distance that needs to be traveled.

Scott at the Lavender Rights Project called for “unrestricted multi-year funding, unrestricted multi-year general operating dollars, both for nonprofits, and also for fiscally sponsored community groups and grassroots funded community groups, so that they can do the work and respond as they need to,” highlighting the ways that many organizations are limited in their ability to respond to the current moment by either their current funding sources or their lack of funding.

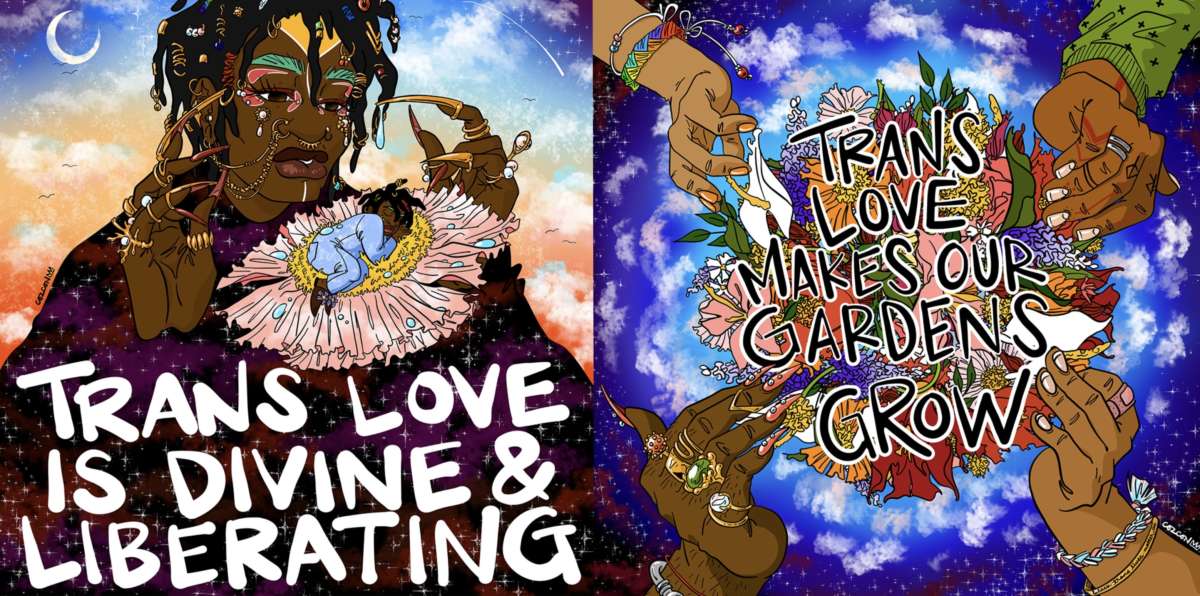

Scott also called for specific kinds of visibility for the trans community in this moment, which should be “less about centering on our traumas and our stories of trauma” and more “centered in Black trans joy, Black trans creativity, and Black trans art.”

The message and work of many of these activists and community members is the one shared by Valentine of the Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition: “Trans joy is out there. It’s within us. We are a beautiful array of identities and beings, and deserving of space, and time and love, and resources…. If you look at history, we were here from the beginning. And we are here now and we will continue to be here as long as there’s an Earth. You cannot erase us.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $29,000 in the next 36 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.