Like many people with a history of drug abuse, 37-year-old Todd Moeller was repeatedly arrested and spent more than 10 years bouncing between state and federal prisons. Then, in 2014, after a stint on the street, he entered long-term rehab and got clean. Something about the treatment plan clicked and a chance meeting with a staffer from the College Initiative program at New York City’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice— a project to enable and encourage people with criminal records to pursue post-secondary study — made him consider something he’d never dreamed possible: getting an undergraduate degree.

It took more than seven months of wrangling, but Moeller was determined. He not only secured his transcripts from a long-shuttered trade school but also succeeded in consolidating the loans he’d taken out to pay for an automotive training course he had defaulted on years earlier when he was incarcerated. That done, he completed a new FAFSA form, met with academic advisers, and in the fall of 2015, enrolled at Hostos Community College of the City University of New York as a fully matriculating student. A year later he is on track to complete his Associate’s Degree in Liberal Arts and hopes to eventually pursue a Masters in Social Work. “I love to learn,” he said. “I came to school with 36 years of life experience and thought I knew everything I needed to know, but taking anthropology and sociology introduced me to so much. I love these fields.”

As he speaks, Moeller repeatedly expresses gratitude toward a host of people, from his family to his teachers and mentors. He further emphasizes that he does not believe that he is exceptional and thinks that the same opportunities that he has been given should be available to all who want them. In addition, he says that he is heartened by a federally funded pilot program that will, for the first time since 1994, allow 12,000 prisoners to qualify for a maximum of $5,775 a year in federal PELL grants so that they can attend college while behind bars.

It’s been a long time coming.

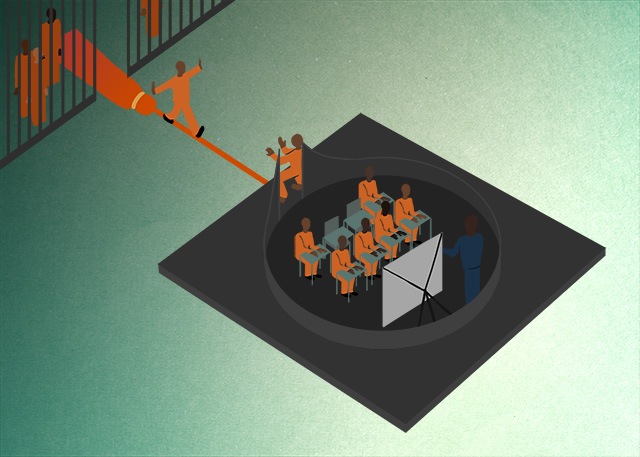

Thanks to a tough-on-crime ethos that dubbed college aid unnecessary, the Violent Crime and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 ended PELL grants for prisoners and reduced the number of jail-based college programs from 350 to less than a dozen, all of them funded by private philanthropy. In fact, in the 22 years since the Act passed, only a handful of colleges and universities — including private schools like Bard, Goucher, Holy Cross, Washington University and Wesleyan, and public institutions like Hostos and John Jay — have successfully raised outside money to bring college to prison. As they see it, education is both a human right and a way to ensure that prisoners can support themselves and their families when they complete their sentences. Advocates also argue — and have been arguing for more than two decades — that the classes prepare students to work collaboratively and become invested in the communities in which they live. After decades of working to promote these ideas, Washington may finally be listening with both ears.

Implementing the Program

Last summer, the Obama administration took a tentative step in undoing the 1994 curtailment of aid: It selected 67 colleges — two-year and four-year, public and private — to teach semester-long courses inside approximately 100 prisons across the country to PELL-eligible students. Some began classes last month but most programs will roll out their curricula in January. The majority of selected colleges, 63 percent, have already been involved in running some type of education program for prisoners, whether GED prep or ESL (GED and ESL programs were not impacted by the cuts imposed by the Crime Act under Bill Clinton’s administration); 37 percent are new to the field. Courses will include a sampling of the liberal arts and sciences as well as vocational education, such as auto mechanics; carpentry; cabinet-making; culinary arts; heating, ventilation and air conditioning; manufacturing; microcomputer applications; and truck and heavy equipment operation.

To enroll in the pilot program, prisoners need to have either a high school diploma or GED. They must also be within five years of release.

The impetus for the three-year pilot initiative — which was promoted by President Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative, the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Department of Education — was pragmatic. A 2013 study, conducted by the RAND Corporation and funded by the DOJ, found that incarcerated men and women who participate in classes are 43 percent less likely to return to prison, and twice as likely to find and keep a job than those who do not. What’s more, the study found that every dollar spent on education saves between four and five dollars in incarceration costs. And, since most prisoners are between 25 and 50 years old and serving sentences of less than 15 years, they will most likely return to their hometowns upon release. What they find there in terms of jobs, housing, support services and opportunities will determine their ability to be good neighbors and active members of their communities.

Ameliorating Poverty and Educational Deficits

Not surprisingly, the link between poverty and incarceration impacts life after prison. The Prison Policy Initiative reports that in 2014, the median income for those entering state prison was a paltry $19,185 — 41 percent less than those on the outside. This makes the notion of a nest-egg to fall back on laughably absurd.

Educational levels are similarly low. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that 68 percent of people entering state prison and 37 percent entering federal prison come in without a high school diploma. This exacerbates financial stress and makes finding a decent-paying job in the above-ground economy nearly impossible. Carceral scholars further note that even a few college-level classes dramatically improve employability and enhance employment options.

Dr. Baz Dreisinger, executive director of the John Jay College Prison-to-College Pipeline, has seen college transform lives. For the past six years, she and her colleagues have taught in four New York state prisons — something they’ll continue through the PELL pilot program. The Pipeline allows students to earn college credits while inside; upon their release they can transfer those credits to John Jay or another college.

Dreisinger notes, however, that for many prisoners, “This is not about a second chance. It’s a first chance for students who did not get educated in their communities in the first place.”

Under-resourced, underfunded and overcrowded schools, she continues, fail large segments of the population. “The people who fill out jail cells come from communities that have been hit hard by systemic poverty and racism. The classes we offer give them what they did not get earlier.”

What they can study has always depended on the institution sponsoring the classes, and the variations will continue under the pilot program. For example, since 2012 Goucher College’s four-year-old Prison Education Partnership — which will expand by 100 students, thanks to the PELL funding — has run classes at the Maryland Correctional Institution for Women and the Maryland Correctional Institution, both in Jessup. Goucher allows students to take a maximum of two classes a semester. “We’ve run 80 classes, most of them 100 level, since we began in 2012,” Program Director Amy Roza told Truthout. “We want the classes to be part of a meaningful liberal arts education that develops writing and critical thinking skills and help students earn credits toward a degree.”

Since its inception, Goucher has been part of the Consortium for the Liberal Arts in Prison, a network of privately-funded prison education programs in 12 states. All fundraise to pay for books, supplies and faculty salaries. “Education typically costs $6,000 per year, per student,” Roza said, adding that she will continue to raise revenue despite the infusion of PELL money.

“The PELL grants will supplement, but not supplant, our budget,” she said. “Plus, some people who want to take classes don’t qualify for PELL. For example, someone is ineligible if he or she started college before but did not repay a loan; they’ll now be in default. There are also some male students who have not registered for Selective Service, which makes them ineligible.”

Promoting Technical and Vocational Training

Not all of the programs focus on liberal arts. Like Goucher and John Jay, Mount Wachusett Community College (MWCC) in Gardner, Massachusetts, was also selected to participate in the Second Chance Pilot. Beginning in January, MWCC faculty will teach in two state facilities and one federal facility. “We’re starting small and anticipate 72 students,” explained MWCC President Daniel Asquino. “The curriculum will be tied to manufacturing. This will be a hands-on, laddered, certificate program and students will take six classes — 18 credits — in things like measurement controls, computer skills, blueprint reading and quality control. There is a huge need in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for people to do this kind of work. There is a lot of industry here, and a lot of large auto parts companies. Cable manufacturing is also a big field.”

Upon their release from prison, Asquino said, students can transfer into MWCC and take online, on-campus, or hybrid classes and complete an Associate’s Degree in 41 majors.

Like MWCC, Lee College in Baytown, Texas, is primarily focused on vocational training for its Second Chance Pilot. The program expects 400 to 500 new students who will choose between an Associate of Applied Science degree or certification in 12 technical fields.

Then there’s Metropolitan Community College in Omaha, Nebraska, which will use PELL funding to offer students “fast track career training” in business, construction, manufacturing and information technology, alongside non-credit classes in financial literacy, nutrition and interviewing and employability skills.

As is obvious, the range of PELL-funded options depends on the sponsoring institution’s priorities and choices — and imprisoned students are restricted by these limitations. In addition, the number of students funded to enroll varies wildly. For example, Centralia College in Washington expects to enroll 12 students a year, while Milwaukee Area Technical College expects to enroll 250, and Jackson College in Michigan expects to enroll 1,300. Dr. Todd Butler, dean of Arts and Sciences at Jackson, said the program will start with 400 to 500 students choosing between eight classes and grow to the 1,300 students and 20-plus courses by the summer 2017 trimester.

Preparing for Life After Prison

Although the PELL Pilot hones in exclusively on educational needs of the incarcerated, what happens to people once they leave prison is of paramount concern to their teachers. Bianca Van Heydoorn is the director of Educational Initiatives at John Jay’s Prisoner Reentry Institute and works with students like Todd Moeller as they make the transition from prison to college. “When you’re able to succeed in college when imprisoned, attending classes in the community is almost a cakewalk,” she said. “Ex-offenders are resilient and something they’ve figured out about the importance of education makes them effectively utilize the programs that exist on both the inside and the outside.” Still, she said, faculty needs to be available to help with the inevitable rough spots. In addition, she notes that “we still have a long way to go in reducing the stigma, discrimination and barriers to employment that exist for people who’ve been incarcerated. The prohibition on associating with other ex-felons is arbitrarily enforced and needs to go since most people end up working in recovery or in agencies with other ex-offenders.”

This is not the only issue that concerns her. The focus, she continues, needs to be on educational justice more generally, and how to increase opportunities beyond the 12,000 individuals who will be deemed PELL-eligible between now and 2019. “We need to recognize that there are many people in prison who are craving an education and who deserve to take their education as far as they can,” she said. “As institutions of higher education, we have an obligation to them, both in jail and at home, in the communities they return to.”

Elys Vasquez-Iscan, assistant professor in the Health Education department at Hostos Community College, agrees. Vasquez-Iscan began teaching Intro to Community Health at the Otisville Correctional Facility, a medium security jail in upstate New York, last spring and works to prepare her students to grapple with some of today’s most pressing health issues, from environmental racism to combating Zika.

Despite frustrations — for example, dealing with clearance delays so that she can screen documentary films and having to rely on a blackboard and chalk due to the absence of computers — she is consistently wowed by her students. “They’re so humble and appreciative,” she said. “Teaching on the outside, you see students who are not invested in their education. In prison, people learn for the love of learning, as a way to become a better person, a better citizen, a role model for their children. It’s not just for a grade or for a degree. These are people who want to get out and give back.”

This is why, Vasquez-Iscan says, expanding education funding for prisoners is one of her top priorities. Like her colleagues around the country, she is supporting the Restoring Education and Learning (REAL) Act that was introduced in the House in 2015 and in the Senate last July. The bill would permanently reinstate PELL for incarcerated people.

Needless to say, the legislation will do nothing to challenge the prison system itself, or change arrest policies. Nonetheless, education activists see it as an important gesture in striving toward equity and providing jailed students with important opportunities that will aid them in life on the outside.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.