It’s taken me a while to get around to Bob Gordon’s stimulating essay suggesting that the great days of economic growth are behind us. It’s not that different from things he’s been saying before, and I have in the past had a lot of sympathy for that view. I now believe, however, that his technological pessimism is wrong — or if you prefer, it’s the wrong kind of pessimism. But this is definitely a discussion worth having.

Mr. Gordon, an economics professor at Northwestern University, argues, rightly in my view, that we’ve really had three industrial revolutions so far, each based on a different cluster of technologies. In an essay published in September by the Center for Economic Policy Research, Mr. Gordon writes:

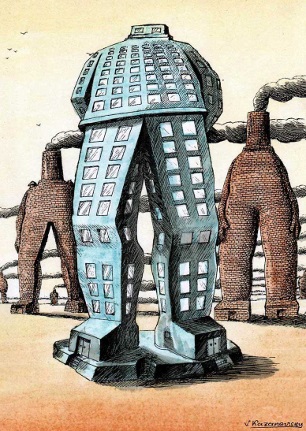

“The analysis in my paper links periods of slow and rapid growth to the timing of the three industrial revolutions: IR #1 (steam, railroads) from 1750 to 1830; IR #2 (electricity, internal combustion engine, running water, indoor toilets, communications, entertainment, chemicals, petroleum) from 1870 to 1900; and IR #3 (computers, the Web, mobile phones) from 1960 to present.”

M. Gordon then argues that IR#2 was by far the most dramatic, which again seems right. Think of the America shown in the film “Lincoln,” which is a society shaped by IR #1 but not yet transformed by IR #2. It was a society in which people could travel much farther and faster than ever before — but when they got to their destinations, they were still living in a horse-drawn society. Most people still lived on farms and the cities were cruder and dirtier than we can easily imagine. By the 1920s, however, urban America was already recognizably a modern society. What Mr. Gordon then does is suggest that IR #3 has already mostly run its course, that all our mobile devices and so on are new and fun but not that fundamental.

It’s good to have someone questioning the tech euphoria, but I’ve been looking into technology issues a lot lately, and I’m pretty sure he’s wrong: the information technology revolution has only begun to have its impact. Consider for a moment a sort of fantasy technology scenario in which we can produce intelligent robots able to do everything a person can do. Clearly, such a technology would remove all limits on per-capita gross domestic product, as long as you don’t count robots among the capitas. All you need to do is keep raising the ratio of robots to humans, and you get whatever G.D.P. you want.

Now, that’s not happening — and in fact, as I understand it, not that much progress has been made in producing machines that think the way we do. But it turns out that there are other ways of producing very smart machines. In particular, Big Data — the use of huge databases of things like spoken conversations — apparently makes it possible for machines to perform tasks that even a few years ago were really only possible for people. Speech recognition is still imperfect, but it is vastly better than it was and it’s improving rapidly, not because we’ve managed to emulate human understanding but because we’ve found data-intensive ways of interpreting speech in a very nonhuman way. And this means that in a sense we are moving toward something like my intelligent-robots world; many, many tasks are becoming machine-friendly. This in turn means that Mr. Gordon is probably wrong about diminishing returns from technology.

Ah, you ask, but what about the people? Very good question. Smart machines may make higher G.D.P. possible, but they will also reduce the demand for people — including smart people. So we could be looking at a society that grows ever richer, but in which all the gains in wealth accrue to whoever owns the robots. And then eventually Skynet decides to kill us all, but that’s another story.

Anyway, interesting stuff to speculate about — and not irrelevant to policy, either, since so much of the debate over entitlements is about what is supposed to happen decades from now.

© 2013 The New York Times Company

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Paul Krugman joined The New York Times in 1999 as a columnist on the Op-Ed page and continues as a professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. He was awarded the Nobel in economic science in 2008. Mr Krugman is the author or editor of 20 books and more than 200 papers in professional journals and edited volumes, including “The Return of Depression Economics” (2008) and “The Conscience of a Liberal” (2007).

Copyright 2013 The New York Times.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.