The Black Lives Matter protests have moved at such a swift pace in recent months that’s it’s hard for me to be certain when I first heard that a national call had been issued, and that January 15th would be a day of action aimed at reclaiming the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. What I do remember clearly is what a young black organizer said as it was brought up in my presence for the first time: “If we’re reclaiming his radical legacy, I’m in.”

Chicago’s young black organizers, who have mobilized with great speed and ingenuity since nationwide protests erupted in August, have been especially creative in their tactics and radical in their messaging. While some of the language employed in their chants and speak outs has included talk of indicting police officers like Darren Wilson, youth organizers from BYP 100 and We Charge Genocide, among others, have also broadened the dialogue around police violence to include the language of de-incarceration, transformative justice, and calls for an all out systems change.

Local activist and teacher Jerica Jurado, whose students have been involved in a number of protests in recent months, credits an already active community of young people for having brought their vision to the front lines. “This isn’t improv,” she said recently, as we discussed the maturity and power of the young activists of color we’ve stood with since August. “They were already out there, organizing for their lives. So, when lightening struck, they were ready.”

I have grown so accustomed to building with these bright young adults that I was expecting more of the same when I was invited to a somewhat clandestine meeting at a Chicago school last month. I was told very little in advance. A friend said my assistance had been requested, and that we would be meeting with a group of students who wanted to organize an action around police violence.

(Photo: Kelly Hayes)When I arrived at the address I was given, I realized it was a school I’d previously visited for an event hosted by Project NIA. The Village Leadership Academy is an independent elementary school that rejects the standard euro-centric learning model employed at most schools in favor of a culturally inclusive curriculum that emphasizes socially just decision making. Even after I realized what building I was walking into, I still somehow expected to see a room full of teenagers and young adults. I was instead greeted by a joyful group of grade school students who were dancing and clapping as they sang, “We are the children of Africa!”

(Photo: Kelly Hayes)When I arrived at the address I was given, I realized it was a school I’d previously visited for an event hosted by Project NIA. The Village Leadership Academy is an independent elementary school that rejects the standard euro-centric learning model employed at most schools in favor of a culturally inclusive curriculum that emphasizes socially just decision making. Even after I realized what building I was walking into, I still somehow expected to see a room full of teenagers and young adults. I was instead greeted by a joyful group of grade school students who were dancing and clapping as they sang, “We are the children of Africa!”

It took a moment for the reality of the situation to fully register. We were, in fact, planning an action with middle school and junior high students. I had missed the first meeting of this budding project, so I wasn’t even sure how such a thing could have developed, but to hear We Charge Genocide organizer Page May explain it, the evolution of the collaboration made perfect sense.

“We were frustrated,” she said. “As young people of color, we didn’t feel like most of the marches taking place in the aftermath of the Eric Garner non-indictment had anything to do with us. We marched in the crowds, but felt like we were still on the margins. So we decided to create our own space, as young activists of color.” As the group invite expanded to include Palestinian youth, and activists from BYP 100 and the Chicago Light Brigade, Page decided to reach out to her contacts at The Village Leadership Academy.

The VLA students Page had interacted with at social justice events had expressed interest in attending protests, in recent months, but their parents had felt the climate of most action oriented events was unsafe for children their age. “I wanted them to help us understand how we could build an event where people their age would feel welcome and safe,” she explained, “but we quickly realized that the VLA students offered more than any of us had hoped for. They had the radical, bold vision and analysis our group needed. In the span of one meeting, they became the heart, voice, and center of our effort.”

The project quickly centered itself around the words and ideas of the VLA students, and what began as a conversation about a simple action in December expanded into a dialogue between the students about why we should organize a march around the Reclaim MLK call to action.

Twelve year old VLA student Kaleb Autman may have explained it best when he told us, “The government made this ploy holiday as a pacifier. This is 2015 and black and brown lives still don’t matter to them.”

Amazed, we sat back and listened for hours, weighing in occasionally with explanations of the mechanics of organizing in certain venues. At first we were hesitant to encroach upon their vision, but over time, we pieced together a process of working in concert. They were the innovators, and we were their helpers and advisers. When their ideas didn’t fit the conditions we knew we’d encounter on the ground, we brainstormed modifications, or other methods of achieving similar ends. Eventually, we realized that we could follow their lead and produce something amazing: a march where even the youngest people of color present could feel safe, speak radically, make demands, and be heard.

Youth organizer Jakya Hobbs works alongside adult allies to create signage for Chicago’s installment of Reclaim MLK. (Photo: Kelly Hayes)

Youth organizer Jakya Hobbs works alongside adult allies to create signage for Chicago’s installment of Reclaim MLK. (Photo: Kelly Hayes)

After a great deal of discussion, the youth reached consensus on a march destination that held great significance to them: the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center. At first, the details of how we would get there were scattered. There was talk of feeder marchers and after school actions. At first, the only things the group could agree upon were the destination, and the first chant they would call out upon their arrival: free us all.

Eventually, the group agreed that we would ask allies to carry out solidarity actions during the day, and march to the detention center in the evening as one group from a single location. “We should march from here,” one of them said as we sat in a meeting at their school, and the profound narrative of the action was suddenly and perfectly clear. These young people were going to lead us down the path that so many youth of color have been forced to walk, from classrooms and cafeterias to cages built to deprive children of their liberty. We would walk there together, join hands and call out to the crowd, the public, and the system itself, “Free us all.”

(Photo: Kelly Hayes)

(Photo: Kelly Hayes)

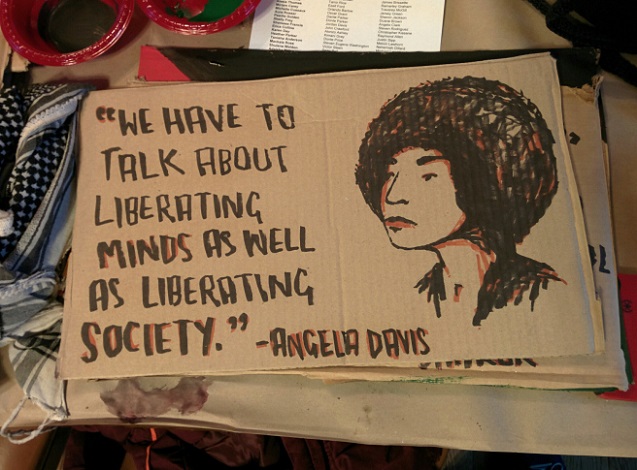

Today, we made signs for Thursday’s event. We centered our imagery around themes the youth had stressed were of great importance to them: emphasizing the role of women in struggle, dismantling the school to prison pipeline, and demanding freedom for youth incarcerated at the detention center.

At the sign making event, young people, who have split into teams to address various elements of the event, from visuals to the list of invited speakers, checked in with one another, painted, sang, and continued to share their vision.

A batch of painted signs, included one inspired by the BYP 100 chant, “We do this for Marissa! We do this for Tanesha! We do this for Mike Brown! We do this for Rekia! We do this for Damo! We do this till we free us!” (Photo: Kelly Hayes)

A batch of painted signs, included one inspired by the BYP 100 chant, “We do this for Marissa! We do this for Tanesha! We do this for Mike Brown! We do this for Rekia! We do this for Damo! We do this till we free us!” (Photo: Kelly Hayes)

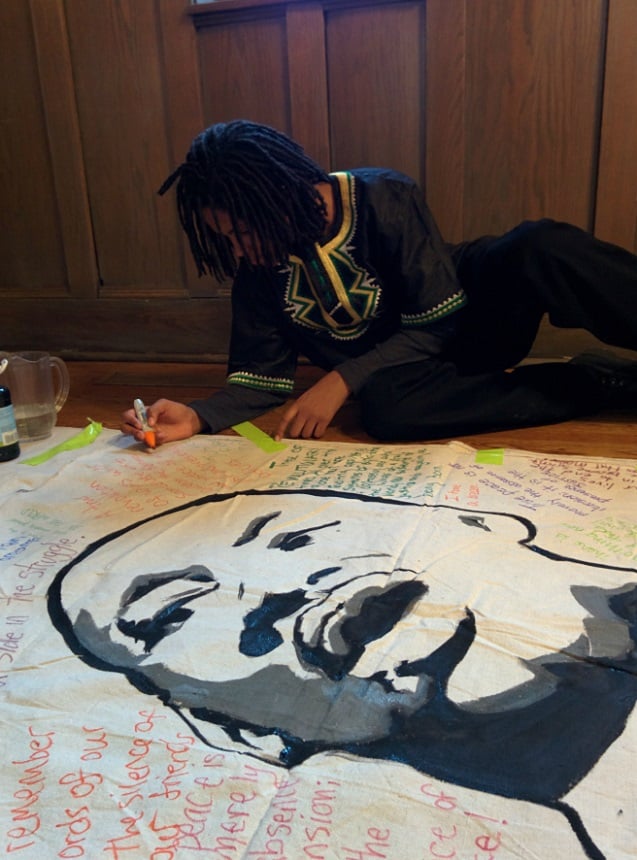

When an ally who was supposed to bring some rip stop nylon for banners was unable to make it, we decided to use one of the drop cloths we’d brought to protect the floors to make a banner for the event. Three of us worked on projecting, tracing, and painting an image of MLK onto the rough canvas surface, while both youth and adult allies used colored markers to write their favorite MLK quotes freely across the banner. Like the entire collaboration, it surpassed our intentions, and blossomed into something beautiful and unexpected.

One of the event’s young organizers, from Village Leadership Academy, Kaleb Autman, works on a banner for the event. (Photo: Kelly Hayes)

One of the event’s young organizers, from Village Leadership Academy, Kaleb Autman, works on a banner for the event. (Photo: Kelly Hayes)

I’m honored that these youth have trusted my friends and I to play a role in what they’ve imagined, and are now bringing to fruition. I was astonished at how many of my own beliefs, that took me many years to develop, are already part of the praxis that they are building together. There is no place in their movement for a sanitized version of MLK’s radical legacy, and with a thousand RSVPs and counting, it’s clear that their vision will define the day.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.