Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

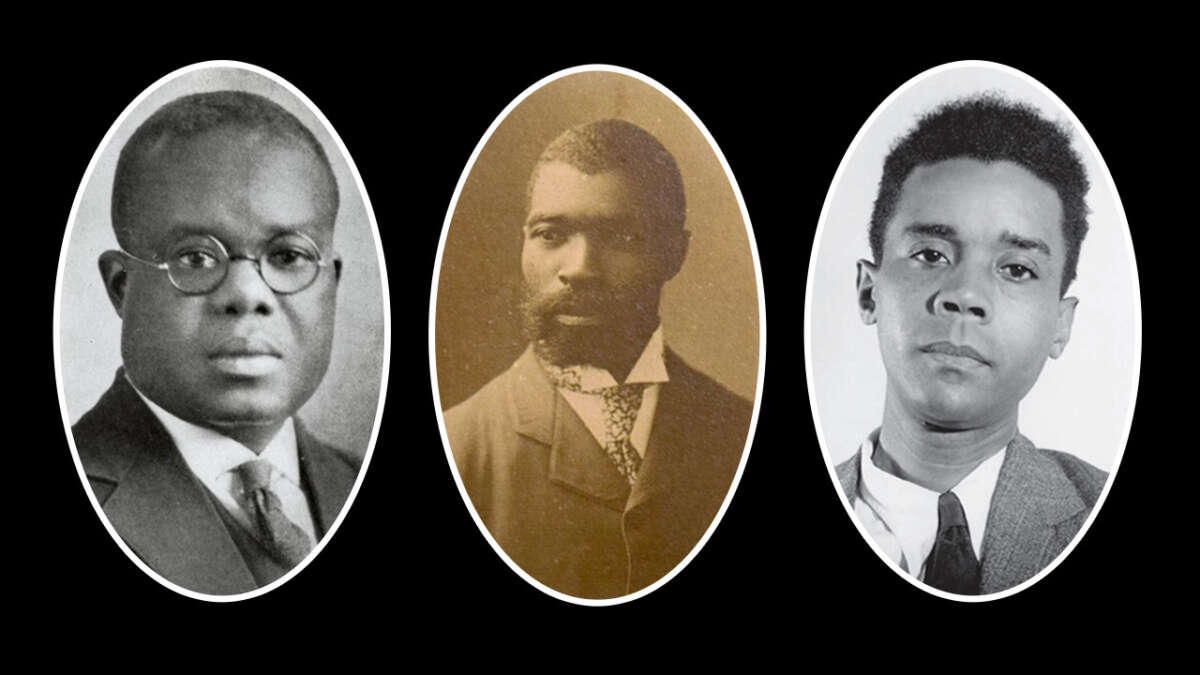

Given the field of philosophy’s paucity of Black or African American philosophers, it is still something of an oxymoron to be a Black or African American philosopher. It is still possible to get second looks when saying, “Oh, I’m a philosopher.” Being a Black or African American philosopher doesn’t compute within a culture, and within academic settings, where images and discussions of Socrates and Plato or René Descartes and Jean-Paul Sartre dominate what philosophy looks and sounds like. In short, white folk continue to comprise the majority in the field: 81 percent. While most of my philosophical work has focused on the meaning of racial embodiment, especially anti-Blackness, and the structure of whiteness, I had the fortune to write and publish the first (or certainly one of the first) essays on African American philosophers Thomas N. Baker and Joyce M. Cook.

Baker was the first Black man to receive his Ph.D. in philosophy, awarded from Yale in 1903. And it was Cook, a dear friend of mine, who was the first Black woman to receive her Ph.D. in philosophy, also from Yale, in 1965. There is serious work that still needs to be done toward the construction of African American philosophy and primary research within the field. The work is out there — but it requires far more, as it were, archeological study. Many celebrate the history of Black Studies and the canonical figures within it, but have little sense of the existence and powerful work of African American philosophers — which is not to say that these areas are mutually exclusive.

It is for this reason that I decided to conduct this exclusive interview with philosopher Stephen C. Ferguson, a professor in the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at North Carolina State University and author of the recent book, The Paralysis of Analysis in African American Studies: Corporate Capitalism and Black Popular Culture. Ferguson is one of the leading philosophers (along with John H. McClendon) whose scholarship has been invaluable in researching, locating, and critically interpreting the history and contemporary relevance of African American philosophy.

George Yancy: When I was an undergraduate studying philosophy in the early 1980s at the University of Pittsburgh, I thought that I was the only Black philosopher in the world. This was partly a function of the fact that I was typically the only Black student sitting in my philosophy classes. I had no idea that there was something called “African American philosophy.” Let’s begin there. What is African American philosophy?

Stephen C. Ferguson: A useful place to begin is with a minimal but clarifying definition. African American philosophy refers, first, to a body of texts written by African American thinkers who themselves understood their work as philosophical. This challenges a long-standing presumption within professional philosophy — that philosophy is defined exclusively by disciplinary recognition rather than by intellectual practice.

Here the work of Black philosopher and theologian William R. Jones is indispensable. In his seminal essay, “The Legitimacy and Necessity of Black Philosophy: Some Preliminary Considerations,” Jones argued that skepticism toward African American philosophy often rests on a mistaken assumption: that race must function as its essential organizing principle. Subsequently, Jones insisted that African American philosophy is not grounded in biology or some sort of “racial essence.” As he put it, “Black experience, history, and culture are the controlling categories of a Black philosophy — not chromosomes.” In this formulation, “Black” denotes an ethno-cultural formation shaped by shared historical conditions.

This does not mean that questions of race are irrelevant. The philosophy of race is an important subfield within African American philosophy. The mistake lies in assuming that it exhausts the field.

Jones therefore urged that philosophy itself be understood more broadly than narrow professional definitions allow. He proposed attending to factors such as author, audience, historical location, and antagonist. From this standpoint, African American philosophy recognizes the philosopher as situated within a specific ethno-cultural community, often addressing that community as a primary audience. Their philosophical point of departure is a historically specific experience requiring conceptual articulation, frequently from an antagonistic position that challenges academic racism in terms of concepts, curricula, and institutions.

Underlying this account is a distinction between race and ethnicity — or more precisely, between race as a classificatory system imposed through domination and ethnicity or nationality as a historically formed collective shaped by shared institutions and struggle. In the U.S. context, African Americans constitute such a distinctive ethno-national formation — forged through slavery, segregation, labor exploitation, and political resistance within a multinational state.

Following Jones, I also draw an analytic distinction between the history of African American philosophers and the philosophy of the Black experience. The former includes all African American philosophers regardless of topic or method. The latter refers to philosophical projects explicitly devoted to analyzing the meaning and consequences of Black life under determinate social conditions. As the number of African American philosophers grows, so too does the range of philosophical problems addressed — many extending well beyond race as a topic.

As an undergraduate, I knew that Martin Luther King Jr., Frederick Douglass, Angela Davis, and others were activists, but no one told me that they were philosophers or that what they had to say was of philosophical significance. The only person who shared this with me was my mentor James G. Spady. Speak to how important it is that this history be told.

I had a similar experience as an undergraduate at the University of Missouri–Columbia. Philosophy appeared almost entirely detached from Black intellectual life. That changed when I met John H. McClendon III. From that point forward, McClendon and I — very much in the spirit of Marx and Engels — worked collectively to recover and reconstruct the African American philosophical tradition.

One of the most important outcomes of our collaboration is African American Philosophers and Philosophy: An Introduction to the History, Concepts, and Contemporary Issues. The work was the result of years of philosophical reading and archival research. What distinguished that book was not simply that it introduced African American philosophers, but that it introduced philosophy itself through the African American philosophical tradition. Before this, African American thinkers were often treated as supplementary figures or “special” topics. Or we might find, in the case of African American philosopher Charles Leander Hill, someone who writes a history of modern Western philosophy. With A Short History of Modern Philosophy from the Renaissance to Hegel, published in 1951, Hill became the first African American philosopher to publish a book on the history of modern philosophy. No one had seriously asked how to introduce philosophy — its core problems and methods — through African American thought. That intervention remains foundational.

This matters because it challenges the assumption that figures such as Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X, or Angela Davis were merely activists. What our work demonstrates is that Black thinkers have produced sustained philosophical reflection on what are often called the “big questions”: metaphilosophy, ontology, epistemology, philosophy of science, philosophy of religion, philosophy of history, and social philosophy. Even when these questions were not framed explicitly in racial terms, the Black experience formed the historical context of their inquiry.

“Examining Ethics” podcaster Christiane Wisehart once described John and me as “philosophical archaeologists,” and that description is apt. Our work represents a first step in the discovery, recovery, and reconstruction of an African American philosophical canon. We do not claim to have completed that task. The hope is that future generations will build upon this foundation, extending the canon we helped recover.

“Historically, Black philosophical traditions emerged less from philosophy departments than from Black intellectual culture — churches, newspapers, political movements, labor struggles, and independent study.”

African American philosophy is best understood as a species of Black intellectual thought. Historically, Black philosophical traditions emerged less from philosophy departments than from Black intellectual culture — churches, newspapers, political movements, labor struggles, and independent study. This does not sever African American philosophy from European or Anglo-American traditions; it gives it a determinate identity shaped by distinct historical conditions. Without this history, students are left believing Black thinkers are philosophical footnotes rather than world-historical contributors.

In your article, “Marxism, Philosophy, and the Africana World,” you argue that the professionalization of philosophy is rooted in institutional racism. Even as a graduate student in philosophy, at Yale and Duquesne University, I was confronted by a sea of white faces. This continues to be true now that I’m a professional philosopher. Say more about how the professionalization of philosophy is rooted in institutional racism. This issue is especially important as we now face executive and legislative policies designed to erase Black knowledge production. Think here of the March 27, 2025, executive order “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” which is aimed at censoring the full truth about the struggle of Black people in the U.S. This executive order, it seems to me, is another manifestation of racism.

To address this adequately, we must begin from a dialectical materialist standpoint and situate professional philosophy within the historical development of the modern university. Specialization and professionalization were not neutral intellectual advances; they were foundational to the university’s role within capitalist society. The specialization of knowledge led to the emergence of academic disciplines; authority shifted from broad intellectual engagement to credentialed expertise. This process established boundaries between legitimate and illegitimate inquiry.

Certain ideas and figures become hegemonic — what Marx famously described as the ruling ideas of the ruling class — while others are disqualified as philosophy and displaced from the academic marketplace. Marxism, for example, is routinely declared a historic failure or an intellectual dinosaur, even as every waking hour of social life under capitalism is organized around the urgent task of making capitalism function.

The exclusion of African American thinkers from academic institutions must be understood through class location and the organization of labor in the United States. From capitalist slavery to sharecropping, and later industrial wage labor and mass unemployment, African Americans were denied the material conditions — time, security, and institutional continuity — necessary for a stable philosophical intelligentsia. Religious institutions therefore functioned as alternative sites of education and abstraction, much as they did for other oppressed groups within the U.S. multinational state.

“The exclusion of African American thinkers from academic institutions must be understood through class location and the organization of labor in the United States.”

The autodidact materialist philosopher Hubert Harrison, known as the “Black Socrates,” exemplifies this contradiction. He produced systematic philosophical lectures such as “World Problems of Race” and works such as When Africa Awakes, yet was denied recognition precisely because his philosophy was embedded in Black working-class political culture rather than professional philosophy.

Dialectical analysis requires us to go further. Even when partial inclusion occurred, new constraints emerged. There remain “ruling ideas” that restrict what African American philosophy is permitted to be — shaping not only who is recognized as a philosopher, but which questions can be asked without professional penalty.

If we examine African American political philosophy across the long Cold War — from the 1950s to the present — a striking pattern emerges. Many African American philosophers aligned themselves with variants of social contract theory — a framework historically used to legitimate bourgeois democracy. From William Fontaine to Bernard Boxill to Charles Mills, one finds a persistent commitment to anti-communist liberalism — often “radicalized,” but liberalism nonetheless. Structural critiques of capitalism, imperialism, and class power are often displaced in favor of moral critique or legal reform. This has been very evident during the Reign of Emperor Trump.

The irony is profound. African American philosophers are often presented as ruthless critics of racism and white supremacy, yet the dominant theoretical orientation has largely avoided questions about the compatibility of capitalism with Black liberation, or the material limits of liberal (bourgeois) democracy.

August Nimtz and Kyle A. Edwards’s work The Communist and the Revolutionary Liberal in the Second American Revolution is instructive. It offers a real-time comparison of Karl Marx and Frederick Douglass during the struggle to abolish slavery. Marx’s and Engels’s writings on the U.S. Civil War reveal abolition not simply as a moral triumph, but as a world-historical rupture between competing social systems: capitalist slavery and industrial capitalism.

By placing Douglass’s liberalism alongside Marx’s scientific socialism, Nimtz and Edwards show that while liberalism was powerful in mobilizing moral outrage, Marxism offered a deeper structural explanation of why capitalist slavery had to be abolished. It was not the fulfillment of liberal democracy, but a contradictory breakthrough that generated new forms of labor exploitation.

The point is not to denigrate Douglass, but to clarify (via philosophical interpretation) the theoretical stakes. Liberalism and Marxism offer fundamentally different diagnoses of power and social change. To remain within liberalism is to risk mistaking reform for revolution.

You’re a Marxist-Leninist philosopher and an African American philosopher. Talk about the complexity of your identity. What does Marxist-Leninist philosophy have to teach African American philosophy and vice versa?

As a good dialectician, I have to point out that the question presumes a distinction that I do not accept. It assumes that Marxist-Leninist philosophy and African American philosophy are identities to be reconciled. My own formation suggests a different starting point.

I grew up in a Black working-class community in the Midwest, raised by parents whose political sensibilities were shaped by the Black Power movement. That environment formed my social consciousness long before I had a philosophical vocabulary. As a young ravenous reader, I consumed whatever was available — Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo, Dickens’s Hard Times and Great Expectations, Langston Hughes, Luke Cage comics, popular history, and political biography — until encountering The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which became a moment of nationalist awakening. That awakening unfolded against the backdrop of deindustrialization, urban decay, and the hollowing out of working-class life in the 1980s and 1990s. The racial character of that devastation was obvious, but so too was its class content. So, my philosophical journey became understanding the class character of racism and national oppression, its roots in world capitalism. This required me to read Marx’s politico-economic works, particularly Das Kapital; Vladimir Lenin’s text, Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism; and Kwame Nkrumah’s Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism. I should add I read C. L. R. James’s masterpiece Black Jacobins in high school.

There is no neat progression “from race to class,” no linear movement from identity to politics. My racial and class consciousness emerged together, forged by the same historical conditions. I became who I was because I am a product of my time. This is precisely the point Marx makes when he reminds us that philosophers do not emerge fully formed from abstract reflection, but from material life itself:

Philosophers do not spring up like mushrooms out of the ground; they are products of their time, of their nation, whose most subtle, valuable and invisible juices flow in the ideas of philosophy. The same spirit that constructs railways with the hands of workers, constructs philosophical systems in the brains of philosophers. Philosophy does not exist outside the world, any more than the brain exists outside man…

My Marxist-Leninist orientation, then, was not an identity choice layered onto an already-formed Blackness. Blackness shaped my motivation; dialectical and historical materialism shaped my method of investigation. That distinction has guided my work ever since.

As I was coming of age philosophically, I intensively read Black philosophers debating whether philosophy could be meaningfully adjoined to Blackness. Against William Banner’s insistence that philosophy must transcend Blackness, Roy D. Morrison (among others) posed a deeper challenge: whether Enlightenment reason itself could be reconstituted from the standpoint of Black historical experience — a project that reads as a prolegomenon to any future Black Enlightenment. Those debates raised a fundamental question: Is Blackness a philosophical perspective, or is it an object of philosophical investigation?

Here Black Studies becomes decisive. Its relationship to the philosophy of the Black experience is analogous to that between physics and the philosophy of physics. Black Studies created the intellectual space in which Blackness could be studied systematically as a material and historical phenomenon rather than treated as a deviation from an assumed universal norm. Philosophy is a critical tool among others for conceptual clarification, critique, and synthesis. It is therefore no accident that early work in the philosophy of the Black experience appeared first in Black Studies venues rather than in philosophy journals, which were far slower to recognize Black life as a legitimate object of philosophical inquiry.

It was through my engagement with Black Studies that I came to understand the limits of bourgeois democracy. And yet, professional philosophy treats bourgeois democracy as the natural — and often the only — horizon of political legitimacy. Among many African American philosophers, this assumption largely goes unchallenged. Questions about justice, rights, and citizenship are routinely framed within liberal constitutionalism, while alternative democratic traditions and historical experiences are left unexplored. Where, for example, are the sustained philosophical engagements with democracy in Cuba, Venezuela under Hugo Chávez, or the Soviet Union? What might these experiences teach us about popular sovereignty, collective decision-making, and mass participation beyond the limits of bourgeois democracy?

This silence reflects the long Cold War repression of socialist political thought. It is therefore telling that figures such as Marxist philosopher C. L. R. James remain marginal within contemporary philosophy curricula. James’s Every Cook Can Govern, a profound meditation on democracy from ancient Greece to modern socialism, should be central to any serious discussion of democratic theory.

As McClendon put it succinctly, Blackness provides the motivation for doing philosophy, not the philosophical orientation. I take that formulation seriously. Marxism-Leninism offers African American philosophy the analytic tools to examine capitalism, imperialism, and the state as material systems shaping Black life. The relationship, then, is not one of identity complexity or reconciliation, but of theoretical necessity.

As African American philosophers, we must do more to get African American students to pursue the field professionally. What strategy do you suggest?

Any serious strategy must begin with an honest reckoning with the history of the American Philosophical Association (APA) and its attendant academic racism.

This was already clear in 1974, when Jones issued concrete recommendations to the APA: placement services, rosters of Black philosophers, surveys of philosophy at Black institutions, graduate fellowships, colloquia on Black philosophy, curriculum development, and the upgrading of philosophy at Black colleges. Since that time, the philosophical landscape has not moved beyond the horizon Jones set. Incremental progress has occurred, yet the overall number of African American philosophers has remained low.

We can no longer wait for professional philosophy to magically deliver Black students into the discipline. We must build our own institutional infrastructure — connected to the academy but not dependent on its permission, promises, or resources.

“Our struggle is an intergenerational relay race: We inherit unfinished questions and are accountable for carrying them forward. No one is coming to do this work for us. The future belongs to those who build.”

Changes in professional philosophy will come through institution-building and long-term strategy, not spontaneity. We must create layered spaces of intellectual formation — archival recovery, collective study, political education, and intergenerational mentorship — inside and outside the academy. Only through institution-building will we sustain a Black philosophical community that revisits core problems at increasing levels of rigor over time.

Forward ever, backward never!

In a moment when Black Studies and ethnic studies face sustained political attack, building independent yet affiliated philosophical infrastructure is not separatism; it is institutional realism.

Our strategy cannot rest on persuasion alone; persuasion presumes institutions are willing to act. History suggests otherwise. What is required is construction. Our struggle is an intergenerational relay race: We inherit unfinished questions and are accountable for carrying them forward. No one is coming to do this work for us. The future belongs to those who build.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 340 new monthly donors in the next 5 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.