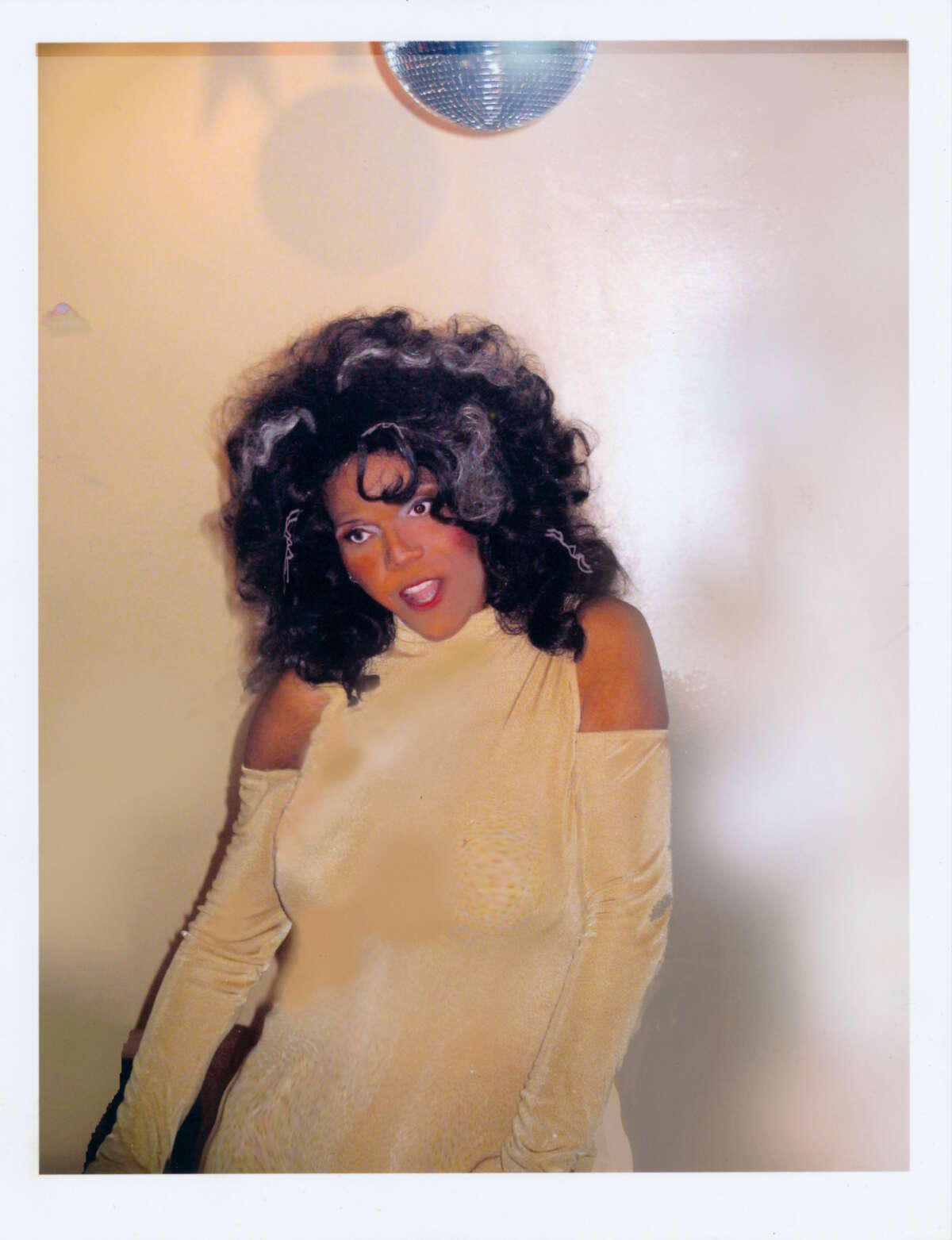

Miss Major Griffin-Gracy is still here, and that is a miracle. The Black, transgender activist began organizing before 1969’s Stonewall riots, and her love for her community has turned her into a mother figure to thousands of queer and trans people around the world. The author, director and activist Janet Mock wrote that Major is “the mother we all deserve.” In 2021, Major and her partner Beck gave birth to Asiah, who became the youngest sibling of Major’s sons Christopher and Jonathan. And many more people who are inspired by Major’s example and consider themselves in a sense to be her children, Major’s never met.

Just by surviving to 76 as a Black transgender woman, she’s done something extraordinary. Within her community, the general rule is you’re doing pretty well if you make it to 35, but the web of relationships she’s made living in New York, California and now Arkansas has been a miracle to the number of people who consider her a parent. Young queers in the ballroom scene of the Netherlands named Major as their symbolic house mother for what they call the Kiki House of Major. In Japan, trans activists know and appreciate her story and activist leadership through an ad hoc effort to translate MAJOR! — the 2015 documentary about Major and her community — into Japanese. (The filmmaker who created MAJOR! was not even aware until 2019 that the film had been translated and was circulating in Japanese to new queer and trans audiences in Japan).

On one of my first assignments for Truthout, I spent a couple of hours in the parking lot outside Miss Major’s Oakland apartment, interviewing her ahead of the release of the documentary about her and the people she loves and cares for. I’d spent so much of the past decade near her, a book came out of it. Now I’m visiting her in her new home of Little Rock, Arkansas, before the May 16 release of Miss Major Speaks: Conversations with a Black Trans Revolutionary (Verso Books). The book is my attempt to distill hundreds of hours of transcribed conversations combining her words and wisdom, to hopefully do for other younger activists what she’s done for me: to inspire and offer strategies and tactics to use in their own work.

Trans people lived precarious lives in 2015, but in the years since that first meeting between Major and I, the U.S. slid sideways into a nightmare dimension where anti-trans rhetoric fills school board meetings, congressional hearings and corporate newscasts. We expect the book will be banned from some libraries simply because Major inhabits certain identities: Black, trans, formerly incarcerated, formerly a sex worker.

Major’s gotten attention for her identities for most of her life, so attention for attention’s sake holds no luster. She’s busy enough with her 2-year-old, Asiah, and mentoring younger trans “gurls” (her way of spelling, inclusively, those who come after her). In this interview, Major discusses Mother’s Day, Miss Major Speaks and the future of trans liberation.

Toshio Meronek: In 2015, you had a retirement party in San Francisco. But that only lasted about a minute. What caused you to come out of retirement?

Miss Major: Well, look around you, where we’re at now. There’s people who need me. And if they need you, you’ve got to respond.

It’s Mother’s Day weekend. How are you planning on celebrating?

A good breakfast in bed if I’m lucky, then going out playing with the kid, and then I’ll get some time alone with Asiah at home. Probably watch some Cocomelon.

What message do you have for all the trans people who will be reading this interview, who may be experiencing a range of feelings about their relationship to motherhood and Mother’s Day?

You know what, they should do what feels good to them. If you like Mother’s Day as a holiday, yay. If you don’t like it, yay! Asiah calls me “mom,” and my oldest is Christopher, who’s 44 and still calls me “Daddy.” I’m trying to lock it all in, [every last title], till everything is a holiday. If your mother doesn’t treat you right, pick another mother.

I was at a meeting where people were being asked their pronouns, and heard someone say, “I go by all pronouns,” which is something I first heard from you.

Good! Maybe it’ll catch on, and people will start thinking beyond the binary — the pink and the blue. That’s the idea behind the book, you know? I think if you read this book, you’ll find that the word “transgender” finally takes on more than one meaning. I would hope that you would step away from this book recognizing that “transgender” does not encompass just one type of person. It’s a term whereby you self-identify — as whatever it is that you feel you are accomplished to be.

A mentor to you while you were locked up at Dannemora [now known as Clinton Correctional Facility] was one of the organizers of the Attica uprising, Frank Smith — also known as Big Black. What are some of the most important lessons you got from him?

Black was ahead of the rest because he saw the big picture, not the little things people were striving for. The way he taught was to take something I already saw glimpses of, and enhanced my vision of that thing. He had such a marvelous brain. And in all of that, he still took the time to talk to me. The first question he asked me is, “What do you go by? What’s your name, baby?”

If your mother doesn’t treat you right, pick another mother.

He brought things into perspective over: We have got to get along with one another regardless of differences that people see. There’s a commonality there that people are ignoring because they’re ignorant and decide to push that out of their mind. And it’s more than just, “We all have two eyes, and two ears, fingers and toes.” Those are really cute things, but the thing is that we have souls and need to connect to each other, to another soul. And we have these emotions, and these thought processes that are connected to feelings and attitudes and dispositions. All that is ignored on a regular basis.

He’s the one that let me know that things like the riot or getting justice done — stuff like that — you can’t throw anybody under the bus. It has to include us all, or it’s not going to work. It was mind-altering. It was like that epiphany that rings a bell in your brain. Bong! That’s what it did. And so, I’ve spent the next 50 years trying to find out what bell I can set off to wake up my community.

Back in San Francisco, protests continue around Banko Brown, the houseless trans man killed by a security guard at a Walgreens store, who was misgendered in the San Francisco Police Department reports. You’ve always been clear on where you stand with the police as an answer to our problems.

The police are not there for us. They protect the wealthy, they don’t protect the poor. So, what do you want? What do you think is fair? They say they’re there to protect us, but they don’t. I don’t care how many trans officers they say they’re gonna hire, those officers are gonna be blue first, and trans second. And since when did shoplifting come with a death sentence?

Since our first meeting, you moved to Arkansas, and we’ve spent time in Florida and Virginia, and you’ve separately been to all the other states in the South. How is it different from the Bay area, or New York, or Chicago?

It’s calmer. The pace is slower. And people have a tendency to mind their own business.

Now the politicians, they’re the same no matter where you go. Anywhere, if you spend time there and look at it carefully, you’ll see that it’s all a matter of what they can present for their own political gains. How they appear. So, San Francisco, or red state, or blue, green or yellow state, it’s all the same. You feed them information until they’re fucking full. And they do nothing for you if you’re poor. It’s not just in Arkansas, it’s everywhere. I wish it were just here.

How do you approach speaking to activists who feel burned out and overwhelmed with life, who maybe have a lot going on personally, but want to be part of the trans liberation movement? I’ve seen you talk gurls down from a ledge.

Well, the thing is, I don’t coddle them. At the same time, if you take on the role of leader, don’t expect people to stay if it’s more than they can handle or endure. People realize what’s going on, and sometimes out of self-preservation they leave.

They have to feel like you’re listening to them. You don’t try to talk over them, or browbeat them or change them, you know, and in listening to them, you give them this sense of respect. My mother and I didn’t get along for most of my life, but when she didn’t want to talk to me, I would just call and when she answered the phone, I would talk to talk, anyway. She wouldn’t hang up. She’d listen. And that stuck with me.

As far as the personal things, find what it is that helps make you feel whole. If you get down, and enjoy walking on grass barefoot, then good, you should do that. Remember to slow down when you need to, and step back. Take care of you. It’s like a car battery: Every now and then, the little line on the dash runs flat. Well, put the motherfucker in neutral, and then get it back in gear and go forward. If you find you’re so overwhelmed that that doesn’t work, then leave and come back when you’re ready.

Ready is coming back knowing that when people harm us, we pay the price for what someone else believes we are, not what we are. The garment that you have to wear as a trans person needs to have some armor in it, but that doesn’t mean you shut your emotions off, or become this bitter, angry, annoying thing. Ready means knowing: “If you’re going to hurt me, I’m going to heal, but you’re not gonna hurt here [Major points to her mind]. And you’re not gonna hurt here [Major points to her heart]. I can take a beating. Beat me, I’ll get better. But then don’t ever fall asleep when I’m near,” you know what I mean?

I do know what you mean — you only ever sleep about four hours a night. On another topic, what role do allies play in trans liberation?

As a community, there’s only so much you can do. We can’t have a March on Washington, D.C. and have 100 million trans women there; there ain’t a hundred million of us. So, our strategy has got to be having the people who do have that force, and those numbers, to help and work with us, to put us in a position to be able to do the things to help us help ourselves. Don’t just throw someone a book on pools and push them in, and go, “Oh, you don’t know how to swim?”

We can’t go it alone. It’s hard… it’s impossible. I mean, you can try, and get knocked down and you can get up and try again, and get knocked down, and then get up and try again. But that’s how it’ll be, until somebody helps you up and says, let me stand with you.

And it’s a good time to get involved with us, but you don’t run this. We run this. You have to listen to what we have to say, and we have to do what we know works.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $34,000 in the next 72 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.