Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

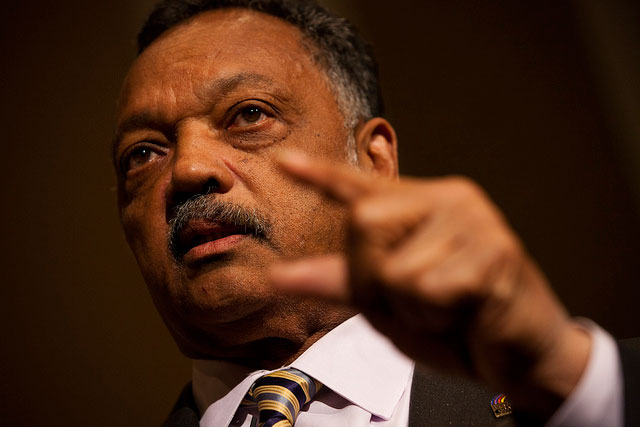

Jesse Jackson spent the morning of his birthday, October 8th, preparing for a “day of service.” A group of Rainbow/PUSH Coalition staff and supporters had gathered at the organization’s offices on the South Side of Chicago for breakfast. Jackson opened the event with a brief speech, explaining that Martin Luther King believed in a birthday celebration consisting of compassion and the cultivation of a thirst for justice. On King’s last birthday, he spoke to student groups, planned the poor people’s campaign and strategized on the most effective ways to galvanize opposition to the Vietnam War.

Inspired by King’s majestic example, Jackson announced that he would spend the anniversary of his birth not in an ornately decorated banquet hall or the embrace of a luxurious party, but inside the thin and cracked walls of Chicago’s underfunded public schools.

Before he left his office, and while his staff and supporters ate a spread of eggs, bacon, sausage, and grits, he told me, “We must have the courage to reimagine our struggle. Even as we gain traction and make progress, we must maintain the ability to see the ways our struggle changes and stays the same.”

While I sipped my third cup of coffee, an energetic, caffeine-free, 73-year-old Jackson continued his eloquent and improvised lecture on the spirit and mechanics of movement politics: “Before we’d march, Dr. King would always tell us, ‘no matter what someone shouts at you – ‘Hey nigger’, ‘Burn in hell’ – just keep looking straight ahead. Keep your eyes on the prize.’ We need to continue to keep our eyes on the prize even as we climb up the ladder.”

The fatal flaw of free-market idolatry and libertarian ideology is that they indulge in the fantasy of meritocracy. “If you study and work hard,” the delusional bromide goes, “you can do anything.”

“We must have the courage to reimagine our struggle.”

Later on Jackson’s birthday, the civil rights leader gave an auditorium full of Latino students at Chicago’s Farragut Career Academy High School, a more nuanced, and more realistic, version of that capitalistic promise: “Why is it that blacks, Latinos and whites can all succeed together on the football field? Why is it that people from all over the world – Mexico, Saudi Arabia – can succeed on the soccer field? It’s because whenever the playing field is even, the rules are public, the goals are clear, referees are fair and the score transparent, we can do anything.”

The prize that must always remain within the sightline of those sweating for justice is the boulder that levels the playing field. Rainbow/PUSH, under Jackson’s leadership, is firing a rock from a slingshot at the Goliath of entrenched and embedded elite interests of American finance and government. The reach of PUSH seems to extend in vastly different directions, but it is always slamming into the slithering wall of discrimination and obstruction.

The march to reimagine the struggle then becomes the work of an engineer; closing the loop on the political, economic and cultural connections from the street to the suite, and from the classroom to the boardroom.

It begins in a place like Farragut High School. Jackson’s sports metaphor was particularly resonant to its students, because Rainbow/PUSH established a relationship with Farragut after learning that the football team did not have adequate funding to equip and protect its players with enough helmets and pads. Many players were sharing helmets, which increases the risk of concussion, and many were unable to practice due to lack of padding. Rainbow/PUSH secured funding for the football team, and in the words of Farragut’s assistant football coach, “Now the players are safer.”

Debates and disturbing discoveries about the dangers of football under any conditions aside, one doesn’t need the imagination of Charles Dickens to realize that high schools on the wealthy, North Side of Chicago – or the rich suburbs – don’t have a problem getting their football players the best, newest and safest equipment. The same is true for excellently trained teachers, current textbooks, classroom technology and basic infrastructure.

The playing field, in innumerable ways, is uneven for the children of Farragut. At birth, the child who lives in a neighborhood with high property taxes, and rich schools, is far ahead of a child in a neighborhood where bullets fly and families fall apart.

Jackson ended his speech at Farragut by asking all the students to stand and join him in the recitation of the “I am somebody” refrain he made famous in the 1960s. The students reacted with a roar, and shouted with the strength of a full-force gale – one girl, standing behind me, fighting back tears – “If my mind can conceive it, and my heart can believe it, I know I can achieve it. I am somebody . . . “

It was a moving affirmation of the students’ basic humanity, and it was an attempt to empower them to speak in the active voice and project themselves as actors, rather than as the acted upon.

The simple story of the dignity of everyday people is one that America often fails to amplify, especially when the invisible hand of the market clenches into a fist and strikes down ties of sympathy and solidarity.

The denial of [Thomas] Duncan’s humanity – the measurement of his life according to a bottom line, insurance card criteria – put his friends, families and neighbors at risk for Ebola infection.

At the request of Thomas Duncan’s family, Jackson and Rainbow/PUSH had spent the day before Jackson’s birthday in Dallas, Texas. At the time, Duncan had not yet died from the Ebola infection that would eventually kill him. Jackson met with the Duncan family, Mike Rawlings, the mayor of Dallas, and discussed the cruelty of the for-profit health-care system. Texas Presbyterian Hospital initially sent Duncan home – even though he had a 103 degree fever and had informed hospital staff he had just returned from Liberia – because he did not have health insurance.

“He was poor. So, in many ways the treatment of him was typical,” Jackson said. “We often talk about the immorality of the health-care system, but this highlights its irresponsibility.”

The denial of Duncan’s humanity – the measurement of his life according to a bottom line, insurance card criteria – put his friends, families and neighbors at risk for Ebola infection. It is chilling to contemplate how many uninsured patients suffering from other contagious diseases are sent back into their homes and offices, without receiving a test or diagnosis, because a hospital deems any effort to save life, reduce pain, or protect people from illness, unprofitable.

Hospitals and schools are public institutions of collective investment and return. If America does not invest the capital, energy and effort to make them great, it should not feign surprise and disgust when men with Ebola wander outside hospital doors back into the street, and children do not, in the words of Jackson, “choose futures over funerals.”

Keeping eyes on the prize while climbing up the ladder means confronting the ugly reality that with each rung there is another layer of discrimination and obstruction.

“The media see the police shoot a black teenager, and think, ‘oh, that’s a black story,’ ” Jackson said, “But they don’t think anything to do with high tech and finance can be a black story. They don’t think it is a diversity issue.”

As much as the horrific murder of Michael Brown deserves extensive media coverage, it does, as Jackson implies, fit the script of the black story. Minority-owned investment firms and Silicon Valley are nowhere near any script. That is why Rainbow/PUSH became shareholders in the major high-tech companies – Google, Facebook, Twitter, Pandora – and demanded that they release their hiring numbers.

Do the boards and management offices of companies communicating with the world, and acquiring the information of billions of people, reflect the diversity of the world?

The high-tech industry attempted to evade this question, some companies even resorted to taking legal action to secure the privacy of their employment data. Jackson and PUSH adapted, while continuing to look straight ahead, by becoming shareholders. If not for the investigation by Rainbow/PUSH, no one could confirm what many have long suspected: The technology industry is overwhelmingly white and male.

Blacks and Hispanics account for 41 percent of American Twitter users, but only five percent of Twitter employees. Pandora is located in Oakland, a city of exciting racial and ethnic variety, but 71 percent of its employees are white. Over a third of its users are black and Hispanic, but its offices are so white a visitor would need sunglasses to make it through the door.

“This is the music industry,” Jackson said, “Where blacks and Hispanics are over-indexed in the product and in purchasing, but not in employment and business.”

It is not just the technical division of these companies that is monolithic, but the management, legal and communication departments. “The only person with a technology background on Zuckerberg’s board is Zuckerberg,” Jackson noted, referring to Facebook founder, Mark Zuckerberg.

“There is not a shortage of talent. There is a shortage of opportunity,” Jackson said, exposing the free market promise of bountiful waters as a mirage in a desert of dry bones. John Thompson, an African American, is chairman of Microsoft, and David Drummond, a black lawyer, incorporated Google. The talent, and often the education and expertise, is there, but the opportunities are behind locked doors.

The same is true in debt capital markets. Rainbow/PUSH has uncovered that most Fortune 500 Companies – from McDonalds to Boeing – have few to no relationships with minority-owned broker dealers.

The free market fails to deliver its promise of access and opportunity without external agitation.

An easy assumption to accept is that once people – of any race or background – acquire educational pedigree and sufficient capital, they’ve made it through the velvet rope and now have VIP access to the American dream. While owners of broker dealers are not comparable to Michael Brown, they are still kept in the basement of the high-finance mansion. A network of cronies combats the diversification of their world, limiting opportunities for broad inclusion of the American polity and stifling potential for minds with the talent of Thompson and Drummond.

“They aren’t George Wallace,” Jackson said describing the owners and administrators of tech companies and major corporations, “but they operate according to cultural blindness.”

In the 1970s, Jesse Jackson organized and oversaw Operation Breadbasket in Chicago. Business owners in the local food and beverage industry actually had the mentality of segregationists. Even though they conducted commerce in primarily black neighborhoods, they refused to hire black people. Jackson’s persistence on the issue resulted in 2,000 jobs for African Americans, and Ebony called him the “apostle of economics.”

Decades later, Jackson is using the same approach of economic evangelism to import the breadbasket all over the country. As Rainbow/PUSH moves from Wall Street to Silicon Valley, they expose the sociology of inequality. “People do business with those they know, trust, and like,” Jackson said before echoing the insight of Joseph Stiglitz that “inequality creates distance.”

“If there is a new shopping mall in development on the South Side of Chicago, who is going to buy up the surrounding properties to prepare for the jump in real estate value? Not the people of the community, but those who know the developers.”

The myth of meritocracy is attractive, but it has no relevance or credibility in the hallways of Farragut High School, at the funeral for Thomas Duncan, or even in the boardrooms of minority-owned investment firms. The score was not transparent in the high-tech industry. The goals of competition are not clear through the cloud of cronyism in corporations, and the referees in Washington DC, having traded in their whistles and flags for campaign donations long ago, are not fair.

On the tech issue, Rainbow/PUSH is organizing a forum and workshop at which they will publish a diversity in technology report, appeal to companies to voluntarily make their employment demographics public from that point forward, and seek commitments for more inclusive hiring practices.

The free market fails to deliver its promise of access and opportunity without external agitation. When I used that phrase with Jackson he quickly added, “External agitation and government enforcement.”

It is impossible to imagine how long the free market would have continued to exclude blacks and women from employment in the professions and financial transactions. Left on its own, it would have continued to punish blacks for being black, and women for not being men.

External agitation and government enforcement not only democratized America, with flaws and failures that still persist, but it also made something resembling a “free market” possible. There is no such thing as “whites-only capitalism” or the “free market for men.”

The weaponry of external agitation is simple. According to Jackson, “We vote; we legislate; we litigate; we advocate; we leverage.”

It is that democratic energy – that fire from down below – that will fuel the drive toward a country worth caring about.

The prize in the eyes of the Latino child on Chicago’s South Side and in the eyes of a black applicant in Silicon Valley, is surprisingly, but assuredly, similar. In the words of the old civil rights anthem: “The only chains we can stand / Are the chains of hand in hand.”

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 340 new monthly donors in the next 5 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.