Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

Barely discernible among the surrounding rock-strewn ground, a meandering dirt track winds its way up a barren, windswept hill. In the arid heat, dotted amid the dry ocher soil, the rocks look baked from the sun. A few stubby trees and scrubby bushes bestrew a landscape with no obvious signs of habitation in this parched land of northern Kenya. But on top of the hill, sitting behind a low wall made of the abundant stones that litter the ground, we find six men. They have been living on the hill for eight years. Every two weeks, food and water is brought up by the consortium that pays them to keep watch on top of the hill, the Lake Turkana Wind Power Project (LTWP).

The incessant wind, gusting relentlessly across the plain, is the reason we’re all here. Shimmering in the heat, Lake Turkana, the largest desert lake in the world, and a United Nations World Heritage Site due to its astonishing collection of hominid fossils dating back 2 million years, glistens in the far distance. The area surrounding the lake is a treasure chest for the study of human evolution, a place where Austrolophithecus anamensis, Homo habilis/rudolfensis, Paranthropus boisei, Homo erectus and Homo sapiens are all found in one location.

One wonders whether wind power for the capital is the answer to the villagers’ development needs.

The lake itself, threatened by the construction of the $1.8 billion Gibe III mega-dam across the border in Ethiopia, is the breeding ground for Nile crocodile, a habitat for hippopotamuses and snakes, and an important site for several species of migrating birds. It’s also home to thousands of nomadic herders and fishers from different tribes in a remote region with only a tenuous connection to the Kenyan state. All of that may well be about to change.

Ljukunye Lepasanti, the liaison officer between LTWP and the surrounding community, tells me he and 28 other workers have been living on top of the hill for the last eight years. “We are here to guard these towers that record wind speed,” says Ljukunye, pointing to one of two tall metal towers on another hill, closer to Lake Turkana. Though the project had been stalled for several years due to a lack of foreign investment, eventually there will be a road built here, and 365 large wind turbines capable of generating a total of 310 megawatts to feed into the Kenyan grid for power to Nairobi. After eight years, does he still believe the wind farm will be built? “Yes, I think so, they are coming to survey the road soon.” Ljukunye’s faith seems justified, as final approval for a financing deal was hammered out at the end of 2014 and documents were signed to begin work in 2015.

Electric Power for Whom?

We are more than 400 kilometers north of Nairobi, where the electricity will be delivered. Many kilometers before the proposed site of the wind farm, the Chinese-built paved road ends before the small sleepy little village of South Horr. The minimally used, shifting dirt and sand road, which winds its way north from South Horr, crosses a flood plain before ascending between towering mountain peaks, twisting and turning along the designated route for the power transmission lines. Before the wind turbines can be brought for assembly at the site, more than 200 kilometers of road have to be either upgraded or built from scratch to get to this isolated region of northern Kenya.

The wind turbines themselves will be offloaded at the port of Mombasa, 1,200 kilometers away. It’s a daunting feat of engineering that makes one wonder: If such a plan is being mooted for a region with so little in the way of modern infrastructure, what should be possible in the developed world? One also wonders, after speaking with local people in the surrounding area, particularly the about-to-be-displaced inhabitants of the Turkana village of Sirima, whether wind power for the capital, along with the associated transmission lines and road construction, is the answer to the villagers’ development needs or priorities.

As the majority of Kenyan power comes from hydroelectricity, climate change is already impacting electrical output and reliability.

The Lake Turkana Wind Power Project (LTWP) consortium is made up of developers and investors KP&P Africa B.V., Aldwych International, the Finnish Fund for Industrial Cooperation Ltd (Finnfund), Industrial Fund for Developing Countries (IFU), KLP Norfund Investments, Vestas Eastern Africa (VEAL) and investors Sandpiper. It’s slated to be the biggest wind project in Africa and, at 70 billion Kenyan shillings (over $760 million), the largest private investment in Kenyan history.

The wind farm is the flagship segment of the Kenyan government’s Vision 2030, which, among other things, is set to enhance electricity production to 5,000 megawatts through domestic means (along with power from the Gibe III dam), and further develop the country via agricultural exports and tourism. The government’s Vision 2030 is based on ensuring extremely rapid economic growth of 10 percent per year to 2030, resting on economic, social and political pillars “to transform Kenya into a newly industrialising, ‘middle-income country providing a high quality life to all its citizens by the year 2030.'”

Kenya is the largest economy in East Africa, in a region of geostrategic importance, but suffers from a dearth of electrical production. In fact, only 18 percent of Kenyans have electricity. For those who have access, supply is unreliable: Power blackouts and failures take place with some regularity. As the majority of Kenyan power comes from hydroelectricity, climate change is already impacting electrical output and reliability, a circumstance that is only projected to worsen.

The 310-megawatt wind farm, which will occupy 40,000 acres around Lake Turkana in Loyangalani District, Marsabit West County, one of the poorest counties in Kenya, equates to 20 percent of Kenya’s currently existing electricity supply and is part of the plan to overcome electricity shortages, which will become more acute as climate change progresses and the projected economic development of the country accelerates. Whether the 82 percent of Kenyans currently without electricity will be the recipients of any of the electricity generated by the wind farm, or whether locals around Marsabit and from the village of Sirima will see any of the jobs or wealth to be created, is another question entirely.

“Long Time Since Regular Rain”

According to the Turkana people we meet in the village of Sirima, due to be moved to make way for the road and wind farm, there used to be regular rains every six months and the locality, unlike today, was always quite green. Now it’s often dry for two to three years at a time, such that even the animals, which are their livelihood as pastoralists, are beginning to sicken. Elder Kwaruk Losike tells us, “It’s been a long time since the regular rains. But now it’s even drier. The small things we try to grow in our shambas (gardens) don’t grow.” The 1,200 people in the village are there because the rest of the community, numbering around an additional 3,000, is away herding their livestock, since, despite a solar-powered borehole well drilled by aid agencies, it’s too dry around Sirima for so many animals.

According to the Turkana people we meet in the village of Sirima, due to be moved to make way for the road and wind farm, there used to be regular rains every six months and the locality, unlike today, was always quite green. Now it’s often dry for two to three years at a time, such that even the animals, which are their livelihood as pastoralists, are beginning to sicken. Elder Kwaruk Losike tells us, “It’s been a long time since the regular rains. But now it’s even drier. The small things we try to grow in our shambas (gardens) don’t grow.” The 1,200 people in the village are there because the rest of the community, numbering around an additional 3,000, is away herding their livestock, since, despite a solar-powered borehole well drilled by aid agencies, it’s too dry around Sirima for so many animals.

While the Turkana of Sirima are currently on friendly terms with the Samburu from the neighboring county, villagers say that they have lost animals to drought and also to raiding by the Pokot and Samburu. Village elders tell us that, as pastoralists, they cannot live without their livestock, but water for their animals, their plants (they have been trying to grow maize, beans, onions and sorghum) and themselves is in very short supply – and salty. During the most desperate times, some food is supplied by aid agencies.

“There were meetings, some people first came in 2008 and began telling us about a road and a wind farm.”

According to the wind power consortium’s website, the “Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programme is being finalised based on extensive input from the communities in order to ensure that livelihoods are improved; LTWP will use a combination of revenue from carbon credits and profit to form and fund a trust, which will ensure a well targeted plan over the 20 years of the investment.” However, the World Bank, in their Resettlement Policy Framework document lists negative aspects of the wind farm that will include “loss of land acquisition, loss of asset, loss of trees and crops, loss of income, and loss of livelihood.”

After sweet chai and honey-soaked flat bread in the center of the village of South Horr, in a shaded garden behind an irregular wooden fence, I meet with Chief of South Horr Alex Lempirias and Assistant Chief Charles Lekaldero to find out what they know of community consultation. “There were meetings, some people first came in 2008 and began telling us about a road and a wind farm.” Asked if they would be getting electricity in South Horr, Lempirias was unsure. “The first thing we asked, ‘what about the locals? Are we going to get the power?’ So he told me this is a question that will come later,” Lempirias said. “There was not that guarantee you shall have it before it reaches the national grid,” even though the transmission line will go directly past South Horr. There is no electricity in South Horr, other than one shop with solar panels, which people use to charge their cell phones; use of the solar panels costs 50 Kenyan shillings per day, a significant sum.

Lekaldero added, “I don’t know if there were any other forums that we never attended that they talked about [electricity for South Horr]. But the forums that I have personally attended, we just talked about the employment and about the CSR. That’s what we only talked [about] in the meetings that I attended. Me, personally.”

The chiefs, who are Samburu, anticipate that they will receive 50 percent of the profits from the carbon credits that will be generated by the wind farm; profits for sale of the electricity go to the Kenyan government. They also hope for 40 unskilled jobs for locals, and compensation for people whose houses have to be moved because of the road and the dust from construction. Their community priorities for use of the profits are “health, education and work. Those are our priorities. Like the community behind here,” says Lempirias, pointing up a distant hill, “that’s about 100 households and no [health] dispensary at the center. They come about 50 kilometers up to here” to reach the nearest health clinic. If they don’t walk the 50 kilometers, he adds, a car to the clinic costs 20,000 Kenyan shillings. With the building of the road, their major concern for their community is the influx of trucks and construction workers, all the water and food they would require, the different cultures coming in and the risk of sexually transmitted diseases, particularly HIV and AIDS, for an uneducated and isolated community such as theirs.

Local Concerns

While the Samburu chiefs in far off South Horr felt relatively confident that they would be treated fairly and compensated appropriately with money and jobs, the three young Turkana women that we met as we came down the hillside where the workers were living on the proposed wind farm site, walking to collect water with their donkeys, threatened to beat us with sticks if we were from the project.

Under the new Kenyan Constitution adopted in 2010, whether there will be compensation for land, housing or loss of grazing land depends on whether the people living there have legal title to the land. According to chapter 5 of the constitution, land should be “held, used and managed in a manner that is equitable, efficient, productive and sustainable.” Due to their longevity on the land, one would think that the pastoralists who live on the land around Marsabit and in other areas of Kenya have been exhibiting all of those features since well before the arrival of the British colonialists.

“Expropriation of land is a very important aspect in land management.”

However, from the perspective of a state whose stated aim is 10 percent economic growth per year, and international financial institutions more than willing to help see that vision come true (at the appropriate rates of interest, naturally), what the pastoralists do with the land is neither productive nor efficient. The constitution designates land as either public, private or community land. Unregistered “trust” land, land held by traditional African customary right of tenure, is held “in trust” by the relevant county government. Though the World Bank notes that the Kenyan Constitution does not speak directly to land acquisition and expropriation, nevertheless the World Bank states that, for Kenya, “Expropriation of land is a very important aspect in land management in that it is the instrument by which land is availed for various development needs e.g. Infrastructure, Housing, Dams and Irrigation, or Industrial purposes if the development and utilisation of the said land is to promote public benefit.”

Though the chiefs in South Horr described the land as empty, with people only grazing their cattle during the rainy season, despite the dryness of the ground, we see sheep and goats being herded by Turkana all across the area of the proposed wind farm. The consortium has agreed not to fence the entire site, only individual wind turbines and the substation. One source of resentment is already evident. Of the 29 workers watching the two wind towers, 26 are Samburu, whereas only three are Turkana. Though the wind farm is on Turkana land, members of the Samburu tribal group are better connected politically than the Turkana, and so seem to have the lion’s share of the current jobs, making future conflict all too possible in such a desperately poor area with a history of conflict over livestock and access to water.

After the encounter with the Turkana women, we drive to the large Turkana village of Sirima, which is going to have to be moved, at least temporarily, to make way for road construction. Due to the extreme aridity of the dry season, herding occurs over tens of miles. Pastoralists range from living permanently in fixed settlements, semi-nomadic – with their semi-permanent homes, called manyatta, made of sticks, hides, dung and rope from the acacia tree – to roaming over large distances with their flocks and herds of goats, sheep, cattle and camels.

We enter Sirima through the traditional fence that surrounds dwellings made of thorny brush to keep out animals and provide defense against livestock raiders. We are taken to the meeting tree and sit down as members of the village gather. Women sit on one side, men on the other. We sit and talk with two elders, Simon Edukon Ekitoe, a former chief, and Kwaruk Losike, as well as a young elder, Lopeyok Logilae. Kitonga, my translator and warrior from the Maasai, speaks mostly in Swahili. A young man stands up to translate into Turkana and repeat both sides of our conversation, people’s mic-style, to the more 100 villagers sitting around the tree.

“Everything is happening with outside people, not with Turkana, even though it’s Turkana land.”

The elders lead the conversation around my questions about the wind power project and how much they know about it. Eight years previously, people came to tell them they would have to move half the village that was closest to the road, though now they have been told they will have to move the entire village more than a kilometer away. They were promised water, and three boreholes have been dug, but the water is salty and some distance from the village. In addition, the solar-powered well doesn’t work well enough on cloudy days, providing only a trickle of water that’s not enough for the many animals that are now brought to the main borehole, which has a storage tank. They did not want to move away from the road because they depend on it for supplies and if someone is sick, but they said they had several meetings with representatives of the consortium to discuss moving. In addition to the water, they were promised a school and a clinic, as well as the building of a market. What they’d really like, Simon tells me, is a wire fence around the village.

Since the last meeting in November 2014, the elders say the village has decided that this is their land and they should be compensated by the consortium for its use. As it’s their land, they believe they should be the first priority, but it doesn’t look like that to them. The elders continue and say they have yet to raise this with the company. According to the elders, the company has said that they will train people to be part of whatever activities take place along the road or for whatever businesses emerge.

By the second hour of the meeting, after finding out more about why we are there and describing the situation with the wind turbines and road, the villagers, through the chiefs, begin to air their grievances and concerns. They note that Samburus are being brought in to do the jobs, not local people and not Turkana. As another village man says, they are upset because “everything is happening with outside people, not with Turkana, even though it’s Turkana land.”

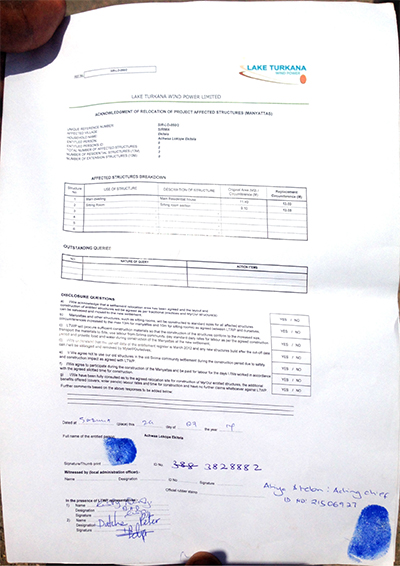

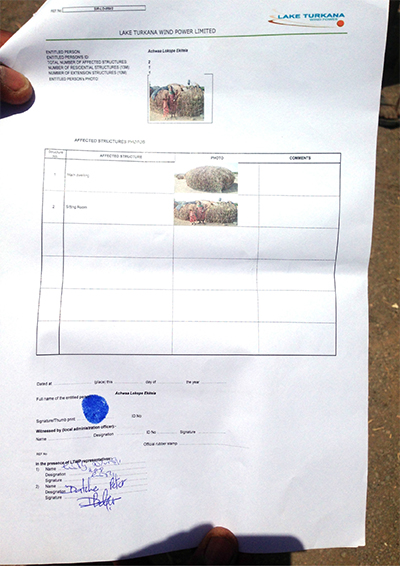

Relocation documents. (Photo: Chris Williams)While they don’t yet know the effect of the wind turbines on their animals, having no experience with them, they have been told that they can graze their livestock around the turbines. They have been stopped from building any new manyatta along the road for the last eight years, even though nothing has happened. If they get the things they were promised, they will be happy, but they have heard that people from another tribe, the Rendille, have demonstrated about the wind turbines but, because the Rendille are far away, the Turkana are not sure why they did so.

Relocation documents. (Photo: Chris Williams)While they don’t yet know the effect of the wind turbines on their animals, having no experience with them, they have been told that they can graze their livestock around the turbines. They have been stopped from building any new manyatta along the road for the last eight years, even though nothing has happened. If they get the things they were promised, they will be happy, but they have heard that people from another tribe, the Rendille, have demonstrated about the wind turbines but, because the Rendille are far away, the Turkana are not sure why they did so.

One of the reasons the Turkana accepted the project here is because they heard about the oil project on the other side of Lake Turkana from Turkana who live there. The oil development by Tullow Oil on the other side of the lake is in fact controversial and the subject of a dispute over who is really going to benefit from the extraction and subsequent burning of fossil fuels, none of which are currently used by the Turkana.

The elders tell us that the company came and took photographs of every person in front of their house. Former chief Simon sends someone to fetch some documents from his manyatta. He returns with papers from the company, titled “Lake Turkana Wind Power Limited.” They are in English, which no one in the village can read, and signed with thumbprints to represent “Acknowledgement of Relocation of Project Affected Structures (Manyatta’s).”

What the villagers don’t know is that as of November 2014, they have now been classified as project affected persons (PAPs) by one of the funders, the African Development Bank, whereby: “The Sirima village is located within the proposed LTWP wind farm site previously designated Trust Land and now leased to LTWP, under a 33 year term, renewable up to 99 years. Under the previous designation ‘Trust Land’ it was managed under the District administration for and on behalf of the community. Consequently, the PAPsnomadic pastoralist have customary rights of use to land pastures, however, have no recognizable legal right or claim to the land other than use and are therefore not eligible for land compensation. There are no land tenure issues for the nomadic communities as LTWP has accepted the cultural ‘right of use’ tenure for grazing livestock and traversing LTWP’s land.”

Which is to say, it’s no longer their land, nor do they have any right to compensation for its use, because it’s been leased to Lake Turkana Wind Farm Project for the next 99 years.

Relocation Documents. (Photo: Chris Williams)The elders, along with some villagers, take me to the place where they have been told they’ll have to move. It’s a much smaller area than where they are, which means their manyattas will have to be closer together than they build them. Unlike where they currently are, they point to the ground and highlight all the rocks, which will make it unsafe for their children and old people. In addition, it’s in a depression in the ground, surrounded by low hillocks, meaning it will be easy for raiders to surprise them and steal cattle. They tell me lots of water drains here during the rainy season, so it will be muddy and unsafe from falling rocks. A single corrugated iron pit toilet built by the consortium, but which nobody uses, sits in solitary isolation in the middle of the desiccated and rocky ground.

Relocation Documents. (Photo: Chris Williams)The elders, along with some villagers, take me to the place where they have been told they’ll have to move. It’s a much smaller area than where they are, which means their manyattas will have to be closer together than they build them. Unlike where they currently are, they point to the ground and highlight all the rocks, which will make it unsafe for their children and old people. In addition, it’s in a depression in the ground, surrounded by low hillocks, meaning it will be easy for raiders to surprise them and steal cattle. They tell me lots of water drains here during the rainy season, so it will be muddy and unsafe from falling rocks. A single corrugated iron pit toilet built by the consortium, but which nobody uses, sits in solitary isolation in the middle of the desiccated and rocky ground.

In many ways Kenya, a country that waged a successful liberation struggle against a ruthless and brutal colonial occupier, presents a similar trajectory to recent analysis of economic development in Vietnam, Morocco and Bolivia, in succumbing to the forces of globalized capital. With a patina of development as “green” and rhetorical flourishes in official documents toward notions of “sustainable development” and “community engagement,” in reality, decision-making has been taken out of the hands of local people at the behest of capital accumulation directed toward tourism, industrialized agricultural production for export, and electricity for the development of a “modern market-based” state and urban Kenyans. Meanwhile, for pastoral and rural Kenyans, the fight to control their own land, in their own interests, continues.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.