Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

Despite efforts to economically colonize the ancient cultures and peoples that populate Morocco, a strong resistance movement is fighting back.

In many ways, Morocco exemplifies the cultural possibilities of a freer humanity. One meets on the streets, fields, mountains and deserts of this geographically and climatologically variegated country, a population universally fluent in at least two languages, many effortlessly switching, mid-sentence, between Arabic, French and Amazigh, the mother tongue of 50 percent of Moroccans. Hospitality to guests is taken very seriously; meals among friends and family are shared and eaten communally, while a common glass is passed around for drinking water. A large percentage of the land is held in common and administered locally by elected tribal leaders for the benefit of all.

A cradle of cultural intermixing, Morocco sits at the crossroads of empires, past and present. A mere 12 miles from Europe, fringed by the warm waters of the Mediterranean to the north, the fisheries of the Atlantic Ocean to the west, crisscrossed by the snowcapped Atlas mountains, providing the lifeblood for the agricultural areas and floodplains of the coast as rivers descend to the sea, and bordered to the south by the gigantic dunes of the Sahara, fading east toward Algeria, its people are comfortable in many social, ecological and cultural worlds.

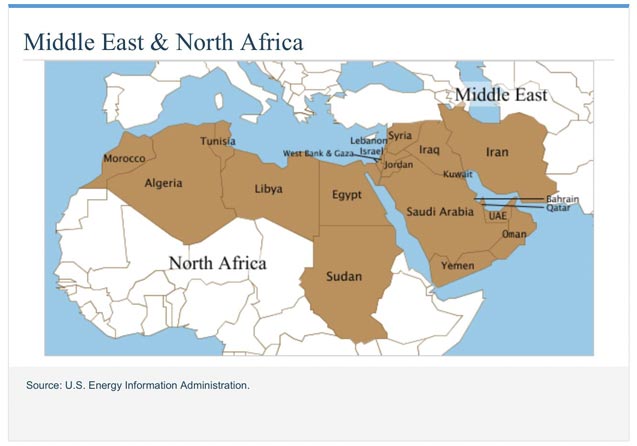

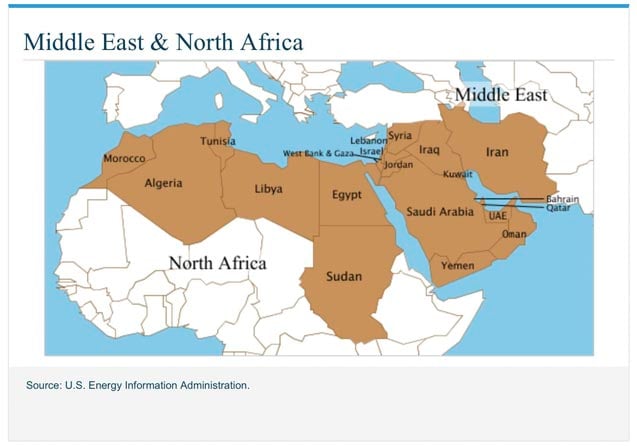

Unfortunately, seldom have Moroccans been able or allowed to decide their own destiny, despite formal independence from the French in 1956. Classified by the World Bank as part of the strategically important MENA region (Middle East-North Africa), a term invented to cover 20 predominantly Arabic countries without mentioning the word Arab, Morocco replicates the colonial moniker of “Middle East” as a designation foreign to the people who live there, but useful for the people who don’t. Al-Maghrib, the Arabic for “Morocco,” translates as “where the sun sets.” For the people who called it home, looking out over the vastness of the Atlantic Ocean (“the sea of darkness”), it was the most westerly point one could go by land. Hence, to be reclassified in the middle of somewhere designated “east,” brings into sharp relief who was making the new maps, and to what aim.

Fig 1: At the Edge of Land, looking west over the storm-tossed Atlantic Ocean (Photo: Chris Williams)

Fig 1: At the Edge of Land, looking west over the storm-tossed Atlantic Ocean (Photo: Chris Williams)

Though many countries in MENA share a common language and religion, they are in many ways a heterogeneous and arbitrary grouping, pulled together by the World Bank on the basis of forming a “market unit.” Despite that, distinguished economically for instance, they straddle the dividing line between oil-rich and oil-poor: 55 percent of the world’s known oil reserves, 840 billion barrels, are found underneath the OPEC countries of the area, along with 80 trillion cubic meters of natural gas (40 percent of world reserves). Yet, countries such as Morocco and Egypt hold none. Naturally, this makes countries on either side of this accident of geology, which intersects with linguistic, geographical, historical and colonial factors in the establishment of national borders, have completely different economic trajectories and levels of development.

After World War II, the recognition that oil was essential to modern warfare, transportation and the newly expanding petrochemical industry made the region the epicenter of geopolitical intrigue, instability and the power plays of nation-states committed to global and regional dominion.

The creation of the State of Israel out of the partition of Palestine in 1948, the ensuing subjugation of the Palestinians and subsequent use of the country to further Western imperial interests, most especially control over the huge concentration of natural resources central to the world economy, lies at the center of the region’s volatility. Once they supplanted the British and French, as a means of securing their supremacy, successive US government’s have sponsored a long line of assorted, unsavory dictatorships and feudal ruling families, whose commonality has been their distaste for democracy and human rights, so fueling further unrest.

Conveniently omitting the influence of great powers’ rivalry, the World Bank described the MENA region as having its “economic fortunes over much of the past quarter century . . . heavily influenced by two factors – the price of oil and the legacy of economic policies and structures that had emphasized a leading role for the state.”

Ever eager to help poor people the world over, the World Bank continues:

With about 23 percent of the 300 million people in the Middle East and North Africa living on less than $2 a day, empowering poor people constitutes an important strategy for fighting poverty. Through a combination of analytical, advisory, and lending services, the Bank aims to provide poor people with the necessary skills, resources, and infrastructure to improve the quality of their lives.

A constitutional monarchy that is in fact ruled in absolute terms by the king, his family and associated elite, Morocco is a country that has closely followed the prescriptions of the World Bank, yet still finds itself with deep-seated poverty, particularly in rural areas, inequality, and only the barest facade of democratic governance. In Morocco, the small number of people who run the country clustered around the king are known by Moroccans as “Makhzen,” which translates as “warehouse,” as they collect and store the wealth of the country and its people.

At the behest of international lenders, between 1985 and 1993, Morocco went through a series of World Bank-mandated structural adjustment programs, which removed subsidies and import controls, and officially joined the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). As a result, Morocco became subject to the vagaries of the world financial system. Though Morocco’s official unemployment rate is “only” 9.1 to 9.5 percent (because this counts only what the government defines as the “active population”), the real number is closer to 28 percent, with a disproportionately high number amongst the rural, non-literate population, which is disproportionally women.

According to Hakech Mohammed, general secretary of the National Federation of the Agricultural Sector, a member of Via Campesina, even though 70 percent of farms in Morocco are less than five hectares (approximately 10 acres), they occupy only 24 percent of the usable agricultural area (UAA) and account for very little of irrigated land. On the other hand, farmers with over 100 hectares and 0.2 percent of the agricultural workforce, control 8.7 percent of UAA.

The Moroccan government, which in practice means King Mohammed VI, and his entourage, along with the leaders of the army, used the recession of 2008, which saw massive amounts of money flowing into agriculture for land speculation, leading to rapid increases in food costs and rioting across the country, to put in place the Green Morocco Plan (GMP). The goals of this plan are to increase the productivity of Moroccan agriculture by mechanization, irrigation and other fossil fuel inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides, while cutting down on labor employment and pay, and to produce crops for export markets rather than subsistence.

Fig 2: In the extremely arid south, villages and trees cluster around precious and scarce water (Photo: Chris Williams)

Fig 2: In the extremely arid south, villages and trees cluster around precious and scarce water (Photo: Chris Williams)

According to Hakech, the results after five years have been a social and ecological disaster. The number of small farmers has decreased, as larger farms and international investors have benefitted from the skewing of grants and subsidies their way; there has been an increase in exploitation of agricultural workers to reduce costs, and a depletion of natural resources, particularly water, as ground water has been polluted from the excessive and often unregulated use of synthetic chemicals. To pay for one year of wheat imports, in a country where voluminous quantities of delicious bread accompany every meal, requires the export of four years of tomato production, the equivalent of exporting vast quantities of water, as traditional techniques for farming are being destroyed.

As Hakech points out, more industrial agriculture, strongly encouraged by the Green Morocco Plan, means an increase in the need for oil, hence making Morocco more subservient to international oil interests. For Hakech, the real solution to issues of water and land, a large percentage of which is held in common, is to remove the elite and the army, who control most of the land, through the rearrangement of social power via a social movement, and redistribute the land with an emphasis on family and small-scale farming that aims to reverse the flow of people from rural to urban areas that is depopulating the countryside, so depleting farming areas of knowledge and labor, and fueling the exponential and unsustainable growth of cities.

Fig 3: Ancient and traditional methods for accessing and preventing the evaporation of hidden ground water are still in use in desert regions (Photo: Chris Williams)

Fig 3: Ancient and traditional methods for accessing and preventing the evaporation of hidden ground water are still in use in desert regions (Photo: Chris Williams)

Without the distorting bounty of fossil fuels, Morocco imports 97 percent of all its energy: natural gas from Algeria, electricity from Spain and coal and oil by ship. At 35 percent, it has the highest illiteracy in the Arab world, a number that can rise to 95 percent among rural women. It is a country particularly vulnerable to climate change, with an increasing number of very hot days, which will increase evaporation from the soil, decreased rainfall, with increased unpredictability and increases in the severity of extreme weather events, as extended droughts or torrential downpours and flooding become more prevalent.

With climate change, an already arid country, one that so lacks rainfall in the south that the country becomes desert, is becoming gradually drier. The MENA region is home to 6 percent of the world’s population, but has less than 1 percent of renewable water resources. Countries such as Algeria, Libya, Yemen, Jordan and Palestine are already suffering from acute water shortages (defined as less than 500 cubic meters per person per year). Just as the rains become less dependable and decrease in amount, a greater and greater amount of fresh water is needed. Irrigation is by far the largest single user of water, at a moment in time when agriculture is being switched to often water-intensive, cash crops for export. In addition, the government is behind plans for a massive expansion of the tourism industry, with the building of giant new tourist resorts.

Fig 4: Though it looks inhospitable, the desert is home to nomadic camel traders and pastoralists (Photo: Chris Williams)

Fig 4: Though it looks inhospitable, the desert is home to nomadic camel traders and pastoralists (Photo: Chris Williams)

The government’s “Plan Azur” calls for the construction of six tourist “stations,” along the Mediterranean coastal area of Saïdia and the Atlantic, covering a total of 7 million square meters. One of the six already under construction, in Saïdia, will “develop” one of Morocco’s most important hotspots of biodiversity, the estuary of the Oued Melouia, home to some of Morocco’s rarest species, living in and amongst its dune forests. The project is to set to accommodate 29,000 beds. But according to engineer and agronomist Benata Mohamed, government worker turned local resistance leader, protests against the project began in 2006 because “they waged a war against nature and against the local population,” as an entire ecosystem, unique to Morocco, is in the process of being destroyed for short-term gain.

To complement the hotel complex, a new marina was built. Unfortunately, as Mohamed explains, the marina has blocked the movement of sand left and right along the beach, which has not only made the marina inoperable due to siltation, but it is also leading to massive beach erosion: In the four years since construction, the beach has retreated 25 meters. This is compounded by the planners who, in order to be more appealing to tourists, want a beach kept free of the local vegetation: exactly the plants that helped keep the beach together in the first place and are essential to the local ecosystem. Hence, within 10 to 20 years, the beautiful beach, one of the main reasons for the original siting of the hotel complex, will be gone.

In the meantime, as their land has been stolen, local people have been concentrated in smaller and smaller areas, the huge increase in demand for drinking water has meant shortages in the nearby city, and a lack of waste treatment and disruption have led to problems with a shrunken bird habitat, once home to over 200 species. The fact that the project is clearly so short-term and unsustainable is not a concern according to Mohamed because “it was never about development, but making a profit by speculation . . . this is a project for the rich people to become richer.” For example, despite digging a canal to prevent flooding of the new tourist complex, the water table is too high, and so the Barcelona Hotel, which was supposed to be open all year round, has only been open for three months at a time.

Mohamed had his eyes opened to wider issues when he learned that the whole Atlantic coast of Morocco, along with the central Atlas chain, the primary source of water for Morocco, has been divided up by oil and gas fracking companies for prospective drilling, with the acquiescence of the king. After seeing the documentary Gasland, he described Josh Fox as his hero because the film is “an extraordinary documentary that woke up the world” and which led Mohamed to organize an anti-fracking conference of all the countries of the Maghreb. Part of the reason for doing so, was because, as Mohamed said, “We need to organize ourselves on the international level, just like the corporations.”

The oil and gas corporations that want to operate in Morocco have been granted 10 years of tax-free status and are allowed to take 75 percent of the revenue. If they find something, they have the right to exploit it for 25 years. But Benata Mohamed, and the democratic ecological and social movement of which he belongs, are not about to give up, despite some recent losses and government repression. As he said, “We are required and obliged to defend our national heritage because if we don’t, they will destroy everything. Everyday you hear about somewhere in the world where people are resisting, and so we know we can fight.”

According to the state energy and water company, ONEE, as Morocco became a middle-income country with annual growth rates of 5 percent, electricity demand, which was a tiny 384 megawatts in 1970, by 2012 had risen to 5,280 megawatts, as electrification took off across the country and many rural towns received their first ever electricity in the 1990s. Between 2000 and 2013 there was an annual increase in electrical demand of 7.3 percent. Demand is anticipated to double by 2020 and quadruple by 2040. Therefore, the question is: How will this be provided? Can Morocco become more “energy independent” by building more hydroelectric dams and allowing Western oil companies to frack for oil and gas? Will the country engage in a dramatic build out of solar power, and if so, how would it transport the electricity from where it would most easily be generated but is also the least populated, in the south of the country, to get to the agricultural areas and population centers of the north? Or will the country continue to build coal and gas-fired power plants fueled with imported gas and coal?

According to government propaganda, renewables are “at the heart of Morocco’s energy plan.” However, there is precious little evidence of that, beyond grandiose plans for 42 percent of electricity demand (of a 50 percent larger total) to be provided from renewable sources by 2020, a mere six years away. The Moroccan solar energy agency MASEN has plans to build 2,000 megawatts of concentrated solar power plants at five sites, though $9 billion is required for the project, money Morocco does not have. Similarly, wind power is set to be developed on 14 sites, also to provide a projected 2,000 megawatts, requiring a $3.5 billion investment.

Fig 5: The old Mohammedia coal plant in Casablanca, recently modernized with money from the European Union. Will more coal plants be the way Morocco provides its growing electricity needs? (Photo: Chris Williams)

Fig 5: The old Mohammedia coal plant in Casablanca, recently modernized with money from the European Union. Will more coal plants be the way Morocco provides its growing electricity needs? (Photo: Chris Williams)

Though more dams are also being built, the existing ones, originally built for flood control and irrigation rather than electricity production, are often below capacity due to changes in rainfall patterns and hotter days. As a lead water engineer responsible for the development of the Mdez dam in the region of Sefrou and the associated river basin told me, the ultimate objective of his job, as described in the 1990s, was to ensure that “not a single drop of water reaches the ocean.”

Much of the water that does reach the sea is heavily polluted from industry, agriculture and untreated human sewage, killing off most of the formerly abundant river life. Less rainfall means an increase in the concentration and impact of pollution. Meanwhile, notwithstanding increases to the amount of land devoted to farming, increased irrigation and the ongoing switch to more water-intensive cash crops, increases in drought conditions and higher rates of evaporation mean there is already a built-in increase in the need for irrigation. Hence, supply is going down while demand is going up for the exact same reason: climate change. A side effect of that process is the increased drilling for well water by desperate farmers. Economics professor Mehdi Lahlou of Mohammed V University in Rabat, and founder of the Association for the World Contract on Water, notes that 20 years ago it was possible to drill down 50 to 60 meters to find a reliable water source. Today, one must drill down 200 to 300 meters.

The conflict over water and the priorities of “development” are perhaps nowhere better exemplified than in Ben Smim, a village of 3,000 inhabitants high in the Atlas Mountains. When a water bottling company first came to the village in 2001, hoping to take advantage of the pure mountain stream water that had sustained the villagers and their cattle breeding since the 17th century, tribal elder Moulay Tahiri Alaoui organized the resistance. A union worker and activist since his days working at the hulking TB sanatorium nearby, built by the French in the colonial period and long-since abandoned, Tahiri knew from the beginning that the people’s water would be stolen and their access restricted. He was becoming progressively more worried about the increasing number of droughts and knew that the villagers’ way of life would be further threatened should the village’s spring be diverted by the Euro-Africaine des Eaux water bottling company.

Fig 6: The village of Ben Smim, after a March snow fall, amid the fertile fields of the Atlas Mountains. The deserted TB sanatorium towers in the background (Photo: Chris Williams)

Fig 6: The village of Ben Smim, after a March snow fall, amid the fertile fields of the Atlas Mountains. The deserted TB sanatorium towers in the background (Photo: Chris Williams)

Over the ensuing years, the villagers staged a heroic resistance, including occupations, petitions and blockades. Women were at the forefront of the protests because they bear the brunt of water-related activities. The authorities responded with repression, arrests, including of tribal elder Tahiri, and for a period of time, the cordoning off of the entire village from the outside world. The protests reached the king, and some compensation and extra jobs were promised, along with new roads, to make up for the ones the company was destroying with their trucks.

The combination of repression, arrests, jail terms and bribes, were enough to force the villagers to concede their historical common water rights. Since 2010, when the company completed construction of the plant and began operation, it has created only 10 jobs and withdraws over 300,000 liters of water a day from the communal spring that is now fenced off. As Tahiri predicted, villagers have been forced to ration water for domestic and agricultural use and move to a multi-day rotation system, whereby houses have water only every third day.

Fig 7: Part of the giant and peaceful union demonstration on April 6th in Casablanca, where February 20th Movement activists were targeted by authorities for arrest, detention and trial (Photo: Chris Williams)

Fig 7: Part of the giant and peaceful union demonstration on April 6th in Casablanca, where February 20th Movement activists were targeted by authorities for arrest, detention and trial (Photo: Chris Williams)

Though repression has intensified, especially against members of the February 20th Movement, which emerged in the wake of the Arab Spring and was central to demands for a new constitution that would reduce the power of the king, people across Morocco continue to organize, most recently in the giant trade union march against austerity on April 6, 2014, when members of the February 20th Movement were again arrested and jailed in an unprovoked police crackdown.

As a young female leader of the movement told me, “Before the movement, we didn’t have a united front. We were aware of all the injustices – women, destruction of the environment, stealing of land. But before the February 20th Movement, we didn’t put all these together.” She continued, “It’s not a question of hope or inspiration; it’s a question of injustice and oppression. If that continues, then so do we.”

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.