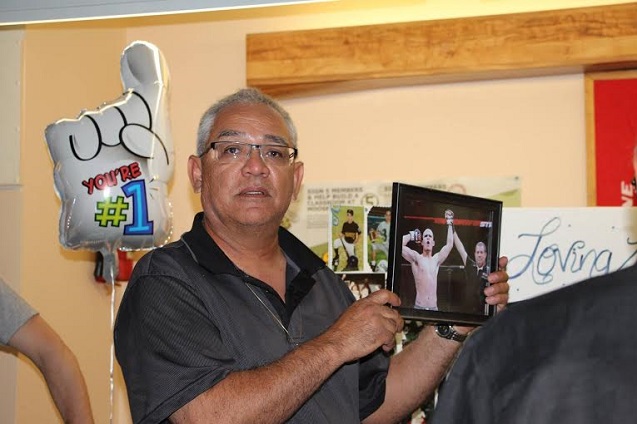

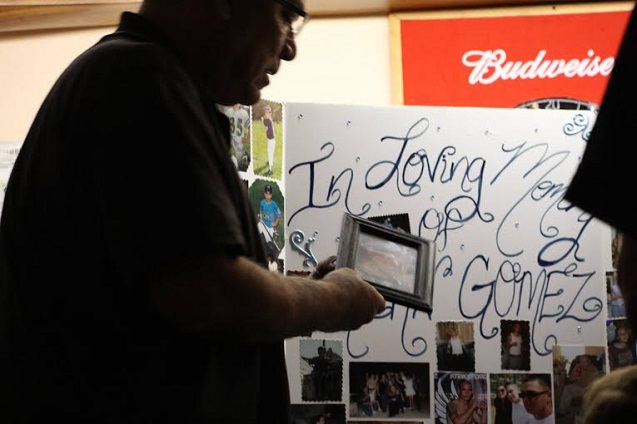

Michael Gomez, dressed in a red button-up shirt, stood silently, his fist raised, at the podium meant for public comment in the Albuquerque council chamber, after putting a picture of his son on the projector. He had his back turned on all nine councilors present for the Thursday night, May 8, council meeting.

“You have blood on your hands,” he told councilors as he was escorted out of the chamber by Albuquerque police. His 22-year-old son, Alan, was shot and killed by Albuquerque officers three years ago this month.

“[The councilors] never listened to us for years. They kind of blew us off as a bunch of disgruntled families,” Gomez told Truthout. “The city leadership is to blame for all this.… They’ve never said they’ve done anything wrong. The mayor has never said, ‘This is my city, this is my department, hold me accountable.’ Not a word. He’s never said that, and he never will.”

Residents and victims’ family members wore red to the meeting that night to symbolize the blood of Albuquerquens that has been spilled by the Albuquerque Police Department’s (APD) use of deadly force over the years. Now, many of those who took a stand at the meeting will not be able to return to city hall for at least 90 days without risking arrest, because they received criminal trespass citations late that Thursday after their protest.

Albuquerque councilors adopted stricter rules for public comment following the previous Monday night’s meeting, during which community members packed the chambers, presented citizen’s arrest warrants for Police Chief Gorden Eden, and effectively shut down the meeting.

Community organizers are also planning a protest march this June, invoking the city’s history of civil disobedience and collective action, and echoing their recent civil disobedience modeled after a particular citizen raid of a northern New Mexico courthouse in the 1960s, in which protesters attempted a citizen’s arrest of the district attorney for allegedly stealing huge swaths of land from Mexican-American residents.

Gomez told Truthout that attorneys from the American Civil Liberties Union (ALCU) have now offered to take some of the protesters’ cases and plan to argue that Albuquerque councilors violated the Open Meetings Act, which mandates public access to proceedings and decision-making processes of governmental bodies. Another organizer said the group is still considering a civil disobedience action by returning to council chambers and risking arrest for criminal trespass.

Since the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) released a scathing report in April documenting the findings of a 16-month investigation into the department and accusing the APD of a “pattern or practice of use of excessive force,” two more people have already been fatally shot by APD officers, fueling a public outcry in a town where the police kill more people per capita than the New York Police Department. Since 2010, the APD officers have been responsible for 39 shootings.

The DOJ investigation found that the APD lacks adequate oversight, adequate investigation of incidents of force and adequate training of officers, and has routinely used deadly force in an unconstitutional manner. The DOJ has laid out 44 specific remedies aimed at rectifying deficiencies within the department.

But community members and families of APD victims are pushing city officials to make more immediate reforms to the police department, rather than wait for the DOJ and APD negotiators to hammer out a consent decree that would set guidelines for new policies and determine how those reforms will be implemented within the department in the coming years.

The preliminary stages of this consent decree process have already begun, with DOJ officials holding meetings with community members and constituents to hear their concerns and recommendations for the new guidelines. Recently, Mayor Richard Berry, whose public presence has been scarce since the release of the DOJ’s findings, called for a meeting with Justice Department officials and residents.

One resident in attendance at that meeting was Charles Arasim, who has been concerned about Albuquerque police violence in the community for years.

“It was the opening salvo … of what is, I believe, the mayor finally coming to the realization that this is something he was going to have to do,” Arasim told Truthout. “Until now, I was starting to wonder if he realized this.” Mayor Berry is just one of the many officials under fire from residents whose distrust for their elected leaders is at an all-time high.

Some changes within the police department have already begun. The police department is now requiring officers to use only department-issued firearms, after the officers’ use of personal weapons was criticized by the DOJ. Thirty-five officers are also already undergoing crisis intervention training, with the goal of having all APD officers certified within 18 months.

But in the mean time, as federal officials meet with residents and small departmental changes begin to be implemented, the only external accountability mechanism in place to oversee the police department, the Police Oversight Commission, is in shambles after three of its commissioners resigned in the aftermath of the DOJ report, writing that the commission “has no teeth” because the city attorney’s office told the commissioners they have “no power to decide against the APD chief or against the independent review officer’s findings regarding citizens’ complaints.”

With the Oversight Commission now in disarray and the community growing increasingly frustrated, frightened and angry, can the DOJ’s consent decree process bring residents the accountability they have sought for corrupt city officials for so many years? Many residents have pointed to areas of daunting silence in the DOJ’s findings and in the city’s proposals for reform, which if left unaddressed, could weaken the overall accountability process.

Dissenters Fear Police Intimidation

Many longtime residents and family members of police victims who have been involved in organizing around the issue of police violence in the city, from attending Oversight Commission, city council and now DOJ meetings, to organizing local protests to speak out against police practices, described living in a constant state of fear of APD officers. They say the officers monitor their protest activities and harass them at their residences for being outspoken about police corruption in Albuquerque in an attempt to intimidate them and chill their First Amendment activity.

“I’ve been followed by the police,” said Dinah Vargas, a community organizer working to end police brutality in Albuquerque. She has compiled a 20-page report of incidents in which she felt she was harassed by APD officers and gave it to DOJ officials during recent talks. She has photographed and filmed many incidents of this alleged harassment.

She accuses APD officers of coordinating efforts to pull over her vehicle without justification, detaining her without justification, and following her and other protesters in an unmarked vehicle, which she said she has seen in her driveway.

“It’s been very intimidating. I’m scared. I do not trust a single police officer whether or not they’re quote-unquote ‘good’ or ‘bad.’ I’m often having a camp out at my house or somebody else’s house because we’re so afraid to sleep alone at night,” she said.

She is not alone. Another longtime resident who has been very outspoken about Albuquerque police violence over the years is Silvio Dell’Angela, a retired Air Force officer and Vietnam veteran. He watched Albuquerque officers shoot and kill his neighbor, Chris Hinz, at his home in 2010 and now organizes locally with a community group, Stop Police Atrocities NOW, and says he has experienced a similar kind of alleged police harassment.

“My wife and my daughter fear as much for life, from being killed from this, from being killed by the police, as the year I spent in Vietnam,” he told Truthout. “I’m not exaggerating about that. [My wife] doesn’t want me to go out to protest. She fears when I go to council meetings to speak, that I’ll be killed.”

Dell’Angela told Truthout that he has experienced direct threats from former Police Chief Ray Schultz in 2010 after he started asking questions, publicly and privately, about why Hinz was killed. Schultz allegedly threatened him, saying he should “be careful.”

“I have no doubts that [Albuquerque police] are tapping my phones, are tracking my car,” Dell’Angela said.

Other sources expressed the same concerns and shared many anecdotes about experiences of police intimidation over the years, from police showing up at their houses unexpectedly, to direct and indirect threats from both officers and city officials.

Further, the culture of repressive conduct against Albuquerque residents engaging in First Amendment activities was well documented amid recent clashes between officers and protesters in Albuquerque, who took to the streets after Police Chief Eden claimed the shooting of homeless camper James Boyd was justified. When protesters marched downtown against police brutality in Albuquerque, they were greeted with tear gas.

Former APD officers agree this kind of surveillance activity is not beyond the pale in terms of the culture of the department.

“With the whole culture of things here, I wouldn’t discount some of that,” says John Doyle, a former APD officer who served for four years in the department before he was fired in 2011 over an excessive use-of-force case. He claims department officials used him as a scapegoat to prove to federal officials that APD leaders were disciplining officers sufficiently and to keep the DOJ from conducting a larger investigation into the practices of the department. His case did not involve deadly use of force.

He said that it is typical of the APD’s Special Investigation Division to put together what’s known as a “red file” on any person who is shot by an Albuquerque officer, which contains a multitude of information about the subject. According to Doyle, the Investigation Division has access to high-tech surveillance equipment and research and intelligence gathering capabilities, which he said could be used to monitor activists and community members who are outspoken.

“I wouldn’t put it past [the APD],” he said. “And now with the city council meetings, they know who the key players are in this, and it’s the people who are fed up with not being heard.”

Thomas Grover, a former APD officer and sergeant, also became fed up with the practices of the department after eight years on the force. He went to law school and is now a civil rights attorney and hopes he can affect more positive change in his new legal capacity. He also agreed the department has the capability to conduct surveillance against the activists, but said it would require a great deal of coordination among officers and likely wouldn’t come from regular patrol cops.

“I don’t dispute that what these people are feeling is that they are targeted, and in some cases they very well may have been,” he said.

Former APD Sergeant Paul Heh, who retired on good terms after working for the department for 25 years, also agreed with Grover that surveillance isn’t likely to come from rank-and-file officers, but didn’t rule out the possibility of surveillance of dissenters entirely.

But what is driving Albuquerque residents’ fear of police targeting and harassment is not just the many incidents they described. Many even say they fear premeditated murder at the hands of corrupt officers and city officials, citing the peculiar case of the death of a prominent — and outspoken — civil rights attorney in November 2010.

The Suspicious Death of Attorney Mary Han

In November 2010, Mary Han, a prominent civil rights attorney and aggressive litigator in Albuquerque who frequently went toe to toe with the APD and city officials over the course of many years, was found dead in what the APD labeled an apparent suicide. But many suspect she was murdered.

In August 2013, New Mexico Attorney General Gary King reviewed the Han case after being prompted by numerous citizen requests, and said that her death should be changed from “suicide” to “undetermined.” He also concluded that high-level APD officials “terribly mishandled” the investigation of the scene of her death.

Han’s autopsy determined she committed suicide, and that the cause of death was carbon monoxide poisoning, as she was apparently found in her BMW parked in her garage.

However, the circumstances of her death included several peculiar characteristics. For example, a very large number of police personnel, up to 50 people, were called to the scene. According to the Albuquerque Journal, the officials included, “then-city public safety director Darren White and his spokesman, T.J. Wilham; then-Deputy Chiefs Beth Paiz and Paul Feist; then-Deputy Chief Allen Banks, who is now the department’s interim chief; Valley Area Commander Rae Mason; then-City Attorney Rob Perry; police crime lab director Marc Adams; and four sergeants, including a designated APD spokeswoman.”

The flood of officials interfered with the material investigation process, according to the state attorney general’s findings. His review of the case also concluded that one high-ranking APD official precipitously decided to label Han’s death a suicide before any investigation was conducted. It is standard departmental procedure that all unattended deaths are deemed suspicious deaths and are investigated by the department, according to Grover.

Han’s family brought a civil suit against the city of Albuquerque and the APD alleging the department mishandled Han’s death scene. The suit has now reached a district court in New Mexico, with a ruling expected in the coming weeks.

According to the plaintiff complaint, in the interim time between Han’s death and the flood of officials at her death scene, Han’s expensive diamond rings, her personal mobile phone and her laptop computer went missing without documentation. The plaintiff complaint names then Deputy Chief Paul Feist as having made the call to process her death as a suicide.

Former officer Grover told Truthout that Han was “like a big sister” to him and inspired him to become a civil rights attorney. They were very close during his time as an officer in the department, and he left the department over the handling of her case. He called the circumstances of her death highly suspicious, and said he spoke with her the night before she died.

Grover has handled many suicide cases, including some by carbon monoxide poisoning, during his time as an officer. He also conducted internal departmental research on the steadily growing rate of officer suicide, which is higher than on-the-job officer deaths in Albuquerque.

“I just could not believe what I was seeing, and what I was seeing I knew was completely wrong,” Grover told Truthout. “I’ve taken suicide or attempted suicide calls before where you’ve got vehicle emissions as the source, and the way she was positioned in her car and the way the car was was not consistent with any of those things, so I was really freaked out and was distraught both on a personal level and as a cop.”

According to police reports, Han was found sitting in the driver’s seat of her car with her feet propped up on the dashboard with the driver’s-side door and the windows open. The door between the garage and the house was also open, which Grover says is inconsistent with vehicle emission suicides, which typically involve subjects shutting all the windows and doors.

He said Han had a lot of insider knowledge about the APD, and he believes she was murdered and her death was staged to look like a suicide. Former officers Doyle and Heh and many concerned residents also believe this.

“Everyone knows if you want to put together a kind of perfect crime, you make it look like a suicide,” Doyle said. “If it can be ruled as a suicide, that cuts out all the investigation.”

Residents put together a chart mapping all the phone calls that were made at the crime scene based on the evidence presented in the plaintiff complaint.

“If I had been there, as sergeant, it would have never happened,” retired Sergeant Heh said of Han’s death. “The [APD’s] top brass would have never gotten into that home. They would have never have violated my crime scene, period. I wouldn’t have allowed it.” Heh had no personal connection with Han and even was her adversary a few times in court.

The DOJ has been silent on the issue of Han’s death, which has become one of the many rallying points for community members engaged with city officials to reform APD practices.

With Whom Is the DOJ Negotiating?

Many in the community are wary of any current APD brass being involved in the process of negotiating the details of the consent decree with federal officials whatsoever, no matter how big or small the details.

One of the major demands of community groups engaged with the city on the issue of APD violence is the ousting, and even arresting, of Police Chief Eden.

Mayor Berry appointed Chief Eden in February knowing Eden would be handling the aftermath of the DOJ’s federal investigation into the force. But Eden has been criticized for much more than claiming that the shooting of Boyd in the Sandia hills was justified and sparking a series of clashes with protesters.

Residents point to Eden’s lack of experience as a primary indicator that he was selected to be a trusted insider who would remain loyal to the city’s leadership and status quo. More than 20 years ago, Eden spent eight years as a U.S. marshal for New Mexico. More recently, he worked for Gov. Susana Martinez, heading the state Department of Public Safety. Throughout this time he forged ties to the APD, including former Police Chief Schultz. He has also openly campaigned for Governor Martinez.

Berry appointed Eden over two other high-profile deputy chiefs from Texas who worked their way up the ranks at larger metropolitan police departments. But Eden has spent most of his recent career as an administrator in state and federal government, not on a metropolitan police force. In fact, Eden’s police officer certification lapsed and hadn’t been valid for more than a decade at the time he was hired.

“You need someone who is a police officer, not was one 20 years ago. You need someone who qualifies to be certified as a police officer not someone whose certification lapsed 20 years ago,” Grover said.

Others who will be negotiating with the DOJ are not coming to the table with a clean slate. After the DOJ released its report, Mayor Berry announced the hiring of former ACLU lawyer Scott Greenwood and former Cincinnati Police Chief Tom Streicher as consultants who would lead a team negotiating the implementation of the consent decree with the federal officials.

Streicher was police chief in Cincinnati during a time when riots broke out in the city because of the actions of divisions under his chain of command. His police department became the subject of a similar DOJ investigation due to rampant racial profiling by the force which resulted in the federal monitorship of his department for six years. Greenwood was also an adversary in that litigation. In the aftermath of the Cincinnati consent decree, Streicher and Greenwood formed their own consulting firm, Streicher & Greenwood LLC, which focuses on “collaborative policing and accountability solutions.” Streicher’s former wife also filed a domestic violence complaint against him and soon filed for divorce in 2001.

In April, Chief Eden named retired commander Robert Huntsman as a new deputy chief tasked with overseeing various DOJ reforms, including crisis intervention training and internal affairs. He helped train SWAT officers in the APD under former Chief Schultz, and that training became part of the DOJ’s finding of a systematic practice of excessive use of force and deadly force in the department. Huntsman also shares very close ties with Chief Eden; they have been described as close friends.

He also happens to be the neighbor of outspoken activist and concerned resident Dell’Angela.

“He could have walked down the street and stopped [Chris Hinz’s] killing. But he never did because he trains the SWAT officers. He trains them, and his mentality is the killing mentality,” Dell’Angela said.

Recently, Police Chief Eden promoted Commanders Timothy Gonterman and Anthony Montano to the newly-created rank of major to help implement reforms mandated by the DOJ’s consent decree. But a federal jury previously ruled that Gonterman and two other officers used excessive force by using a stun gun on a homeless man in 2002. The formerly homeless man was awarded $300,000 in 2006 for his suffering from second- and third-degree burns.

It’s these primary players, among other city leaders, who are raising alarms for community members seeking accountability after years of corruption.

“It definitely has a taint of more of the same,” resident and activist Arasim said of the negotiators. “There had to have been better choices.”

But the background of officials in charge of working with federal officials to implement changes within the APD is not the only problem.

Contract Kickbacks From Taser?

In July 2013, former Chief Schultz signed a no-bid contract with Taser International for officer lapel cameras, costing Albuquerque $1,950,000 — the largest contract Taser has ever won.

Only a few weeks later, Schultz officially retired, and Taser announced Schultz as a new consultant, triggering an inquiry by city council members into whether or not Schultz violated the city’s conflict-of-interest ordinance, which mandates that former employees must wait at least one year before representing any “business in connection with a matter in which the former employee has performed an official act.”

While he was still police chief, Schultz allegedly sent an email message to Taser representatives telling them that “the approval process for the contract ‘has been greased.'”

The DOJ’s finding’s letter concerning APD abuses dedicates seven pages to officers’ abuse of Taser stun guns. Federal officials reviewed more than 200 incidents involving Tasers, finding that officers’ routinely used the stun guns unjustifiably.

The exclusive use of Taser stun guns and other products as well as Schultz’s new consulting position certainly suggests he received a kickback from the company in the form his new high-paying job in exchange for a multi-million dollar contract.

Retired Sergeant Heh filed a complaint with the New Mexico Attorney General’s Office requesting the office investigate former Police Chief Schultz over his connections with Taser International, and Heh said the office is reviewing the complaint to decide whether or not to move forward.

Sources told Truthout that many of the vendor contracts APD relies on for equipment and weapons have spiked and quadrupled in the last few years, with the majority going to friends of APD brass.

Now, the two men hired as consultants to the APD to oversee negotiations with the DOJ also have connections to Taser. Streicher and Greenwood, alongside former chief Schultz, also do consulting work for Taser.

This is another area in which the DOJ’s silence has been deafening for the community.

“There’s a whole lot of doubt cast on how honest and transparent the whole [consent decree] process is going to be,” former officer Grover said.

Will Top Brass Be Prosecuted?

Community members pushing for accountability want to see APD leadership investigated and prosecuted by the DOJ. Many have called for a full takeover of the APD by federal officials.

The DOJ is investigating individual officers involved in deadly use-of-force incidents, but whether or not investigation of top brass is on the table remains to be seen.

The public information officer to the U.S. Attorney’s office for the district of New Mexico and the public information officer at the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division Special Litigation Section did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

“If history is any guide then [this process] won’t work,” said David Correia, a University of New Mexico American studies professor and local organizer, pointing to the Walker-Luna report, which documented some of the exact same systematic problems recently found within the APD that the DOJ released back in 1997. After the report came out, reforms were implemented in the department by some of the same figures who are still in charge.

“As a result, six years after those reforms, [the APD] killed more people at a higher rate. So there can be no day-to-day control of the police department by Eden, Huntsman, any of the deputy chiefs, or [Mayor] Berry, but the DOJ won’t go that far,” Correia told Truthout.

That’s the point behind the growing protest movement, which hopes to pressure federal officials to make the leap from investigating use-of-force encounters to investigating APD leadership.

“Until we understand the kind of connection between the kind of corruption going on at the highest levels of the police department and how that cascades down and produces a use-of-force culture, we’re never going to root this out. This is not just that we have bad cops, poorly trained and badly led; it’s that we have a corrupt police department that produces these outcomes,” Correia said.

The DOJ’s report doesn’t tell the whole story, and it’s the silence on many aspects of this corruption that is standing in the way of accountability for Albuquerquens who’ve lost relatives and friends to police violence over the years. It’s these aspects the DOJ must acknowledge as it moves into the consent decree phase, which will work on a much longer time frame — as residents may continue to be killed by APD officers in the interim.

“The DOJ is like a freight train; once it gets going, it takes a whole lot to get it to stop or change direction,” Grover said. It’s why it remains crucial the train takes off in the right direction, he emphasized.

Correia concurred. “If we’re just satisfied with the DOJ report and the consent decree, we’re not going to get anywhere. We’re going to find ourselves 10 years from now saying the same things we’re saying now because every 10 years we do that in Albuquerque,” he said.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $225,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.