Janine Jackson: There is such a thing as a company simply having too much power; even without evidence of malign intent, it just isn’t healthy.

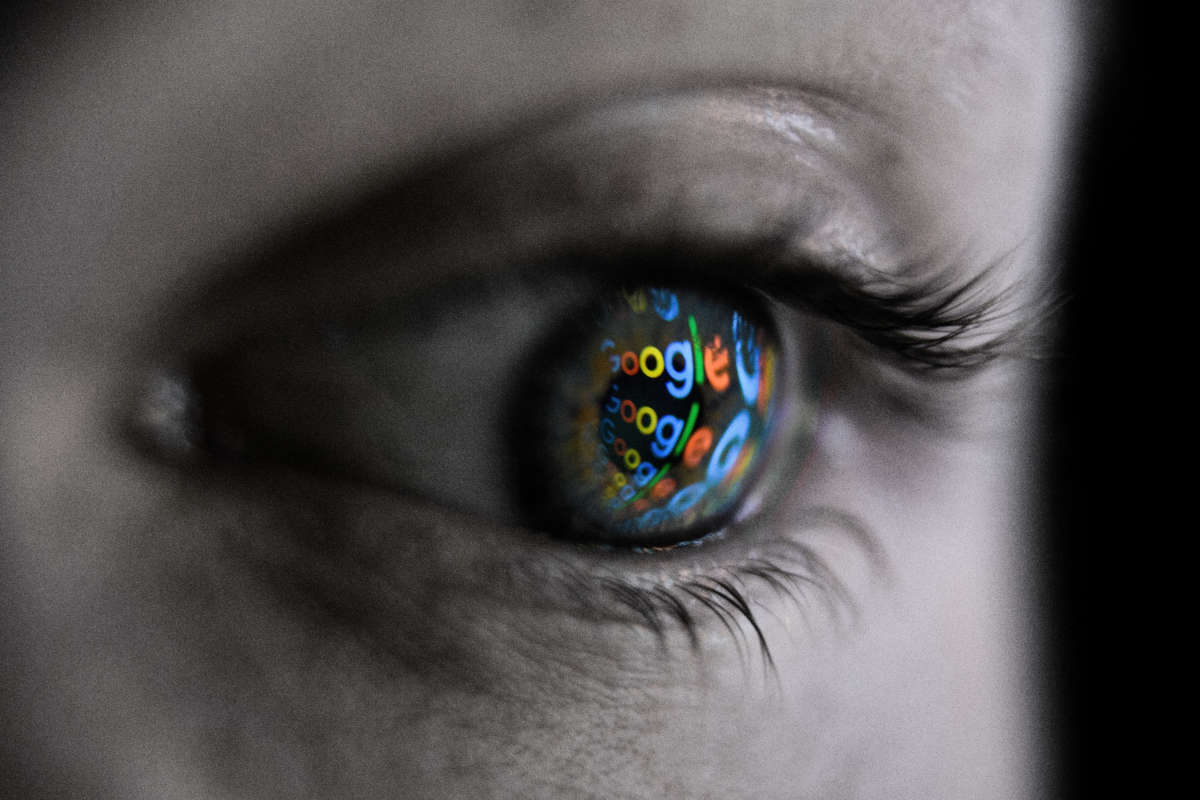

That’s the basic thinking behind antitrust law in this country. And if the power is over something so critical as our ability to obtain and share information? Well, that’s the concern behind the push to break up Big Tech. And while it may seem quixotic, it’s at least a step away from the notion that the internet is such categorically new territory that it can’t–or shouldn’t–be regulated to serve the public interest.

Several corporations are in the spotlight, each with different issues of concern, but right now, an antitrust lawsuit against Google appears to be gaining ground that our guest says has the potential to be very important indeed.

Mitch Stoltz is a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. He joins us now by phone from the Bay Area. Welcome to “CounterSpin,” Mitch Stoltz.

Mitch Stoltz: Thank you, happy to be here.

A quick bit of background first: This antitrust lawsuit is coming from the Justice Department and state attorney generals, based on their own investigations. In layperson’s terms, what is the complaint?

The complaint is under something called Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act, and that’s a law that says if you are a monopoly — that is, if you have power over the market for some good or service — then there are things you can’t do. You can’t use improper means to maintain that monopoly power, you can’t try to gain monopoly power in other markets, various other things.

But what this suit says is, they’re claiming that Google has monopoly power in internet search and in search advertising. So those are the two markets they’re talking about. And they’re claiming that Google has illegally maintained that monopoly power, particularly through the contracts that it makes with various other companies — so phone vendors and web browser makers, and various other companies that it does deals with — it often requires that those companies put Google Search in a prominent position, and not allow rival search engines to occupy such a prominent position.

From my point of view as a user, Google is free to me, so how would I be made aware, or aware at all, of any monopolistic power going on? How can a free service also be a monopoly?

Well, “monopoly” just means they have the dominant position in the market, and the ability to set price or to set the level of quality. And so when you’re talking about a free service, often then what the courts will look at is: Can they stop innovating? Can they actually provide an inferior product that people will still use because there isn’t really an alternative?

I wanted to ask you about one thing that I know that EFF has thought about. We think about privacy a lot. I think if folks think about, “Who can see my searches, what I do on the internet?” I had a very smart friend say, “You know, I just assume everything I say online is observed.” And I think there’s this acceptance of a tradeoff: You just trade away your privacy and your civil liberties, and there’s no way to get what the internet would give you without doing that. And you’ve been thinking about different ways to think about privacy as a value. I wonder, could you talk a little about that?

Sure. In the context of an antitrust suit, that loss of privacy is the monopoly price, essentially. If you’re talking about groceries or gasoline, if there’s a monopoly situation, you’ll be paying more than you would otherwise. But with Search, because it’s a free product, the issue is you’re not paying more in cash; you’re paying more in loss of privacy than, presumably, you would if there were competition.

And there is, by the way, there is competition; it just has not been really able to flourish, because of some of these exclusive contracts, or preferential contracts, that Google uses. For example, there’s a search engine called DuckDuckGo which does not track its users; they’re not based on the user’s browsing history, but only on the search that they’re making at that moment, and it doesn’t track them from search to search. And that exists, but it has a real hard time competing against Google because of — and this is according to the lawsuit — some of the conduct that Google does in a way to maintain its monopoly.

We have to think about — and you note this as well — the power of the default. An alternative might be out there, but if when I turn on the screen, this is what comes up, well, then that’s going to be what I’m going to tend to use, and I may not even know that those alternatives are out there at all.

That’s really central to this lawsuit. Many of the specific things that DoJ and the states are complaining about are the defaults that Google insists on, on things like the homescreen of a phone, even Apple phones, as far as the placement of Google Search.

Right. It’s kind of like if your waiter says, “Do you want Coke or Pepsi?” and, well, you should have somehow sensed that you could have asked for milk, but it’s going to be people’s tendency to choose from what is put in front of them.

A lot of folks express frustration about lawsuits against mega-companies, because often what comes out of it is a fine, and we know that these companies just factor fines into the cost of doing business. But this Google antitrust suit isn’t talking about damages. What is it asking for?

It’s pretty broad. What it’s asking for is basically a court order to stop the illegal conduct. So at this point in a lawsuit, it’s pretty common not to specify what remedy you want in very specific terms, because it’s going to be connected to exactly what the court finds was the illegal conduct.

Right.

They talk about “injunctive remedy,” which means an order not to do something, and they talk about “structural remedy,” which could mean a breakup of the company, but in Google‘s case, and in the case of this lawsuit, it’s not really clear what a breakup would look like. I mean, you could potentially separate Google Search from the Android operating system, or Google Search from Google web advertising, or something like that, but none of those really flow directly from the things that the governments are accusing Google of here.

So probably most likely what this is moving towards is an ongoing monitoring of Google’s conduct, and some rules about what they can and can’t do. In that sense, it’s very much like the government’s lawsuit against Microsoft, back in 1998, where they actually had pursued breaking up Microsoft into an applications company and an operating system company, and the trial judge actually ordered that to happen.

But then the court of appeals said, “We’re not going to break up the company, but we are going to put limits on its behavior.” A lot of folks think that it was those limits, and just being monitored by the enforcement authorities at that point, that caused Microsoft to shelve its plans to maybe squash some new and upcoming rivals–like Google, which was a brand new company at the time.

That’s very interesting.

Yeah.

You make clear in your writings, and as you’re saying here, that this lawsuit doesn’t touch everything. Folks are going to say, “Wait, when I think about problems with Google, I think about, you know, the way they treat their workers, or algorithmic bias.” The story right now is the firing of Timnit Gebru, the AI researcher. You make clear that there’s plenty that this suit doesn’t touch, but that doesn’t mean that it’s not still a valuable effort; you think that it could still bring some things to light that could be useful?

Absolutely. One of the trickiest parts of any antitrust suit is called defining the market. If Google really only competes with Bing and DuckDuckGo, then Google’s pretty clearly a monopolist. But if you define the market more broadly, such that Google Search competes with the telephone book and Amazon’s product search and various travel search companies, suddenly it starts to look like less of a monopoly. And that’s often the really fundamental question in an antitrust case.

Just getting to that question, and having a court resolve that question, will really change the legal landscape for the tech world, because the information that gets brought to light, and the court’s conclusions, are things that can then get used down the line in other things, in private suits, in challenges to all those things, to their employment practices, to their various other company policies. Each one of these is a building block, is what I’m saying.

Right.

Antitrust law is narrow. Antitrust is focused on the harms caused to consumers by a monopoly. It’s not necessarily a vehicle for things like employment concerns or environmental concerns, although those do get brought in sometimes.

Right. Well, it can do what it can do, and then it’s for others to take the information that is brought to light and use it in various ways.

Let me ask you, finally: CNN’s Brian Fung seemed to throw up his hands after one of the House Judiciary Committee Hearings that folks may have seen over the summer and into the fall. And he wrote:

The Big Tobacco moment isn’t coming; there will be no damning self-incrimination on camera that leads to a dramatic and wholesale reversal of fortunes for Big Tech. The reason is simple: Nobody can agree on what the problem is, let alone the solution. And the companies are so large, and touch so many aspects of our lives, that it has been nearly impossible for lawmakers to focus on a single issue for more than a few minutes at a time.

Now, I understand that frustration with the hearings, after watching [Tennessee’s Sen.] Marsha Blackburn use a congressional hearing to ask [Google CEO Sundar] Pichai, “Hey, did you fire that guy that said those mean things about me?” But Congress is one arena, the courts are another arena. We don’t have to choose just one place to make these arguments for transparency, for equity, in terms of the internet, do we? We’ve got multiple fronts here.

We do. And I think the states are also going to be an increasingly important arena for this kind of oversight.

You know, when I tried to look up media coverage about the antitrust suit, I saw allusions to Google as “used to be cuddly, used to be scrappy, but then it lost its soul and grew up,” or whatever. News media tend to anthropomorphize businesses in a way that I don’t necessarily think is all that helpful. Maybe we need some better frames to talk about how we can improve these systems that don’t make it sound like, you know, Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots.

I feel like the tech companies, they defied gravity for 10+ years there; they got an exemption from the public’s general hostility towards big business that sort of came crashing to Earth in the last three years. And ultimately, that’s healthy, because they should be treated with skepticism; as much as we love their products, as much as we depend on them — and so many of us still do — it’s also healthy to cast a skeptical eye on them. And to recognize the problems that technology can’t solve, the problems that are human problems that show up at Google, and Facebook and other places, just as they do in tobacco or oil or other industries that have been in the spotlight.

We’ve been speaking with Mitch Stoltz. He’s a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation; you can find their work online at EFF.org. Mitch Stoltz, thank you so much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

Thank you very much.

We have 9 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.