Indiana Gov. Mike Pence (R) ignited a national firestorm last week after signing into law the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which critics argue provides a “license to discriminate” against gay people and others. Angie’s List, Apple, Yelp and other companies condemned the move and even threatened to nix expansion projects in the state, prompting the governor to say he wants lawmakers to “clarify the intent” of the law.

But just as Indiana’s law was gaining national infamy, North Carolina lawmakers introduced matching Religious Freedom Restoration Act bills in the state House and Senate — and according to legal scholars, the legislation introduced last week could pose an even greater threat than Indiana’s to civil rights.

As in Indiana, proponents of the North Carolina Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) argue the legislation is modeled on a 1993 law passed by Congress and signed by President Clinton. The federal law proclaimed that the government cannot pass laws that “substantially burden” people’s ability to follow their religion, unless the state can prove there’s a “compelling interest” in doing so and has no other way to meet that compelling interest.

In 1997, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the federal law applied only to the federal government, spurring a number of states to enact their own RFRA laws — a trend that has grown in the wake of debates over gay civil rights and marriage equality.

However, the measure proposed by North Carolina lawmakers differs from the federal law — and “religious freedom” laws in most other states — in at least one key respect: It makes it easier for individuals to claim a law or policy is a threat to their religious beliefs, and to sue to opt out of complying.

Under the 1993 federal statute and most similar state laws, the person using RFRA has to show that obeying a law — for example, complying with a local ordinance preventing housing discrimination for a gay couple — would pose a “substantial burden” to following his or her religious beliefs.

But the proposed North Carolina bill dilutes that language, requiring that those claiming their religious liberty is at risk prove only that obeying the law is a “burden” — substantial or not.

Of the 19 other states with RFRA laws, only two — Alabama and Mississippi — omit the word “substantial.” In the South, existing laws in Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia all include the “substantial burden” standard, as does a proposed (and hotly-contested) measure in Arkansas.

That small change in wording could have big legal consequences. As conservative legal scholar Eugene Volokh notes, while it’s clearly difficult to define what constitutes a “substantial” burden, several courts have used the “substantial burden” test in deciding whether challenges under state and federal RFRA laws are valid.

Others say that the weak language in bills like North Carolina’s sends a dangerous message that such laws can be deployed as a “trump card,” allowing religion to be used as a reason to disobey the law. In 2014, the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, which supports “religious freedom” laws, sent a letter to state legislators in Georgia condemning a bill (HB 1023) for omitting the “substantial” provision:

HB 1023 … differs in significant ways from the version of RFRA that the BJC has supported. These differences raise concerns about striking the right balance when religious liberty interests conflict with other important governmental interests, including the prohibition on government establishment of religion. Notably, HB 1023 just says government cannot burden religion — it doesn’t include the important modifier that the burden must be substantial. . . . Without the substantial burden requirement, nearly any state law or regulation could be subject to exemption challenges. While religious liberty is one of our most precious rights, it is not an automatic trump card.

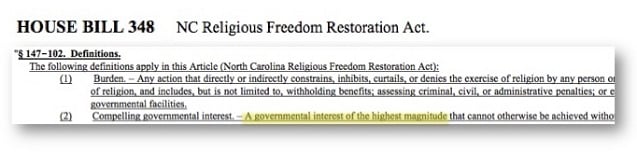

The North Carolina bills include other language that favors those who claim their religious rights are being infringed. While the federal law and Indiana’s state that there must be a “compelling governmental interest” for infringing on religious beliefs, North Carolina’s goes a step further, stating there must be a “governmental interest of the highest magnitude” (emphasis added) to justify overriding religious beliefs. While “highest magnitude” isn’t defined, the Baptist Joint Committee notes this is a “hurdle” not required in the federal law.

The future of N.C.’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act is unclear. Gov. Pat McCrory (R) has expressed skepticism about the bill. As The Washington Post notes, the vehement reaction against Indiana’s measure points to changing public attitudes that make passing such laws more difficult — and the political fallout more damaging.

As Chris Sgro of the advocacy group Equality North Carolina said after the North Carolina bills were filed:

Nobody wants to see this. You’ve got a handful of legislators that are pushing this on the state of North Carolina. It shows … how out of touch the General Assembly is with North Carolina.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $41,000 in the next 5 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.