Cheryl thought she was home. After 18 months without shelter, five of them spent living in her car, she finally found a subsidized apartment in Old Orchard Beach, Maine. A housing voucher enabled her to pay $600 of the $1,035 market rent, something she could manage on her cashier’s salary.

Eight years passed. Then, a year ago, Cheryl’s life was again upended when she learned that her building had been sold and the new owner wanted to convert the five-unit dwelling into short-term vacation rentals. On June 4, 2022, she received a notice to vacate and on July 4, she put her possessions in storage and headed to the first of two shelters. She remained undomiciled for 11 months.

Thankfully, Cheryl’s story has a relatively happy ending: On May 25 of this year, she moved into a new apartment. But her rent has climbed to $810, and even with a subsidy, she knows that this is going to be a stretch. What’s more, her new home is in Sanford, 25 miles away from her previous community.

Still, Cheryl knows that she is lucky. As part of a growing number of housing-insecure people over the age of 50, she is well aware that many elders languish for years without a permanent address, living in street encampments, cars, parks, or temporarily doubled or tripled up with friends or family.

According to PBS, people over age 50 currently comprise approximately 50 percent of the unhoused population, up from 37 percent in 2003 and 11 percent in 1990. Even more dramatic, projections posit that the number of homeless people over age 65 will triple by 2030 in major U.S. cities like Boston, Los Angeles and New York.

There are multiple reasons for this unprecedented spike, among them: skyrocketing rents, the end of the COVID-19 eviction moratorium, ageism, a weak social safety net, an insufficient supply of affordable housing and soaring medical debt.

And then there’s our overall economic system. Eric Tars, legal director of the National Homelessness Law Center, says that the crisis is the direct result of unfettered corporate greed. “Global capital has been buying up foreclosed properties all over the country,” he told Truthout. “They are using housing the same way mining companies have used the Earth and are attempting to extract wealth from our communities. Just as there are environmental impacts from strip mining, there are environmental impacts from wealth mining.”

Longtime housing activist Diane Nilan, founder of HEAR US: Giving Voice and Visibility for Homeless Children and Youth, agrees but also sees the increasing number of homeless elders as a sign of our deterioration as a society. “When old folks don’t matter, when you throw old folks out of their homes, we’ve lost it as a society,” she said. “It’s frightening. For too many people, GoFundMe is the only option to remain housed.”

Many shelters, she adds, do not allow pets, and for many vulnerable people, animals are their only family. In addition, those tenants receiving Section 8 subsidies are bound by stiff regulations promulgated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) that bar them from taking in an aging relative. In fact, guidelines stipulate that a guest — no matter if it is mom, dad, a grandparent or another family elder — can stay with a prime tenant for no more than 21 days in a calendar year. Violation can lead to eviction.

Illusions About Family Support Hurt Elders

“If you’ve worked a minimum wage job your whole life, you likely don’t have much saved so you have to keep working into your 70s or even 80s to stay in your home,” Pennsylvania housing activist Pat LaMarche told Truthout. “People typically don’t want to be a burden to their families, especially if they have health issues, and they feel humiliated when they end up on their grandchild’s couch.”

More ridiculous, she continues, people who are doubled up are not considered homeless by HUD because they do not meet HUD’s definition of homelessness. Moreover, she says that people tend to romanticize the idea of a multigenerational home. “Living with multiple generations is not always something poor people in overcrowded apartments can do,” LaMarche said. “Most poor people don’t have a financial cushion. One thread gets pulled and everything unravels. The mythology around this is infuriating and is a cruel reflection of society’s general lack of respect for the autonomy of older people.”

Projections posit that the number of homeless people over age 65 will triple by 2030 in major U.S. cities.

Then there’s the economic reality: According to the Social Security Administration, the average 2023 retirement benefit is $1,834.80 per month; the average monthly disability payment is $1,483.93. Disabled and elderly people who did not work the required 40 quarters — long enough to qualify for benefits — can apply for Supplemental Security Income, or SSI. As of this January, the maximum monthly SSI benefit for a single person is $934; disabled or elderly couples can receive a combined monthly grant of $1,391.

For many people, this is less than their monthly rent: As of May 2023, rent.com reports that the national median rent is now $1,967. More incendiary, rents have risen 16.33 percent since 2021, reflecting an annual increase about 8 percent or more than $250 a year.

The impact has been dramatic: The poverty rate for people over 65 went from 8.9 percent in 2020 to 10.3 percent in 2021, and while 2022’s 8.7 percent Social Security cost-of-living increase helped, it did little to stem the tide of housing loss for seniors.

Their stories are filled with desperation and angst.

Fifty-six-year-old Brooklyn, New York, resident Brett, for example, began to feel the punch of housing insecurity two years ago when he fell behind on his rent. “I lost one of my two jobs as a security guard during the COVID shutdown,” he told Truthout. “I’ve been in my apartment for 20 years. I live alone and pay $800 a month in rent. New York is an expensive city, and during the worst of the pandemic, I could not pay my bills. I owe my landlord about $5,000 and am trying to work out a payment plan to reduce the arrears,” he said. “I’ve been trying to get a second job, but my landlord needs to cut me a break and let me pay off what I can when I can.”

Paulette, another Brooklyn resident, has also fallen on hard times. “I’m in my 70s and the eviction threats have been active,” she said. “I pay $990 a month and during COVID, I had an accident and broke my clavicle. This made me get behind in my rent. I owed the landlord about $12,000 from 2020 and 2021 and received a year’s back rent through the state’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program. That program is now closed, but I still owe my landlord a little bit. The rent never stops.” Paulette said that due to her immigration status, she can’t receive Social Security, so she finds other ways to earn money. “I help friends with chores, recycle bottles and cans, and get help from the community food pantry. But if I get evicted? No. No. That can’t happen. No.”

But many people cannot stave off a marshal or stop an eviction.

Karen, age 64, lost her Carlisle, Pennsylvania, home of 43 years in March 2021 after a neighbor complained about the deteriorated condition of her single-family home. “Six police officers came in with building code officers and my husband and I were given two hours to leave. At the time we had 13 cats. The officials condemned our house and I had to get special permission each day to go in and feed the animals and remove some personal belongings,” she told Truthout. “I was able to rehouse the cats, and for six weeks, my husband and I stayed in a hotel paid for by family, friends and strangers who responded to a GoFundMe appeal. We begged the borough to help us fix the house and repair the structural damage. They refused.”

Karen says that her husband died nine months to the day after they were evicted.

Since leaving the hotel, Karen has been staying with one of her three children. “I’m comfortable,” she said, “but it has been devastating. I went from being in the same place for four decades to being on an air mattress in my daughter’s living room. It’s lovely and it’s miserable because this is not my home.”

Karen has applied for subsidized housing and is hoping to find an apartment in the near future. “I have MS [multiple sclerosis] and want to stay in Carlisle because my health care is here,” she said. “My sole income is $1,222 a month in widow’s benefits, but my health is crummy and I’m afraid. All of this is challenging for me. It’s actually really daunting.”

Cheryl, Brett, Karen and Paulette are not anomalous; at the same time, we still do not know exactly how many seniors are teetering toward homelessness.

“We often can’t identify older people who are on the edge,” Ann Oliva, CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness, told Truthout. “We know older adults are a critical population to be concerned about, but we can’t definitively enumerate the year-to-year changes in this demographic.” This is why she and other advocates are calling on HUD to change the way data is collected and reported.

Each January, Oliva says, HUD does a point-in-time count on one night to identify folks who are in shelters and on the streets. People who fly under the radar, including couch surfers like Karen, result in a severe undercount. In addition, Oliva says that the count only divides people into three categories: those under 18, those 18-24 and those over 24. “We want HUD to break the numbers into smaller age categories,” she said. “Their longitudinal studies do this but they are not up to date. The most recent is from 2019-2020.”

This leaves advocates and activists with little concrete data to go on. “We know anecdotally that people are aging in homelessness and we’re seeing a lot more people over age 50 entering the system for the first time,” she continues. “Shelter providers tell us that family members are literally dropping their loved ones off when they can’t take care of them anymore. Most shelters are ill-equipped and workers are burned out. They leave to take jobs at places like Home Depot where they’ll make more money and feel less stress. We are not keeping up with the need.” Furthermore, she says, shelter providers understand that older people typically have different needs than younger people.

“We see that rents are rising fast and people on fixed incomes can’t keep up,”

Oliva adds. “Seniors should at least be given rent increase exemptions if we want them to remain housed. We also need to build more robust connections between homeless advocates and offices for the aging throughout the country. These are now overlapping constituencies.”

Creating Special Housing for Seniors

Lisa Glow is the CEO of Central Arizona Shelter Services (CASS) in Phoenix. The 600-bed congregate care facility provides beds for people of all ages, but staff are currently renovating a hotel that will be tailored exclusively to people over age 55. The program will provide temporary transitional housing — Glow says that ideally people will be placed in permanent homes within 90 days, but she recognizes that it may take significantly longer — along with three meals a day, mental health counseling and transportation to medical and other appointments. Last year, Glow reports that CASS served 1,717 people over the age of 62, nearly a third of the 6,658 served that year and a 43 percent jump from 2021.

“The system is broken on so many levels,” she said. “Hospitals discharge people to CASS when they have nowhere else to go and we’ve set aside a percentage of beds for hospital drop-offs. We will do the same at the hotel when it opens at the end of this year. We can provide respite, but we are not a medical facility. We’re understaffed and under-resourced and have been for decades. The droves of seniors who are becoming homeless are perplexing.”

I went from being in the same place for four decades to being on an air mattress in my daughter’s living room.

Solutions, she adds, are obvious: We need rent controls and rent increase exemptions for seniors and the disabled. We need to build more affordable housing and we need to provide low-income people at risk of eviction with a no-cost attorney. We also need a better social safety net to help with medical and mental health concerns.

“We need the political will to build housing for low-income seniors and we need neighbors who welcome affordable housing and poor people into their communities,” she says. “When there is a hurricane, FEMA rushes in and takes action, but homelessness has been an ongoing hurricane for decades and there’s been very little action to help people.”

But that may be changing. “We have been fighting for the principle that housing is a human right for decades,” Eric Tars of the National Homelessness Law Center said. “For years, we were told that this was an aspirational, pie-in-the-sky demand, but the idea has entered the mainstream and there is now a lot of dialogue about this idea.” Tars said COVID pushed it to the foreground. The Housing is a Human Right Act has been reintroduced, he says, and folks are increasingly out in the streets marching for housing justice. “The rhetoric is changing. The right to profit from housing, and the idea that property rights are supreme, is now more widely contested,” he adds.

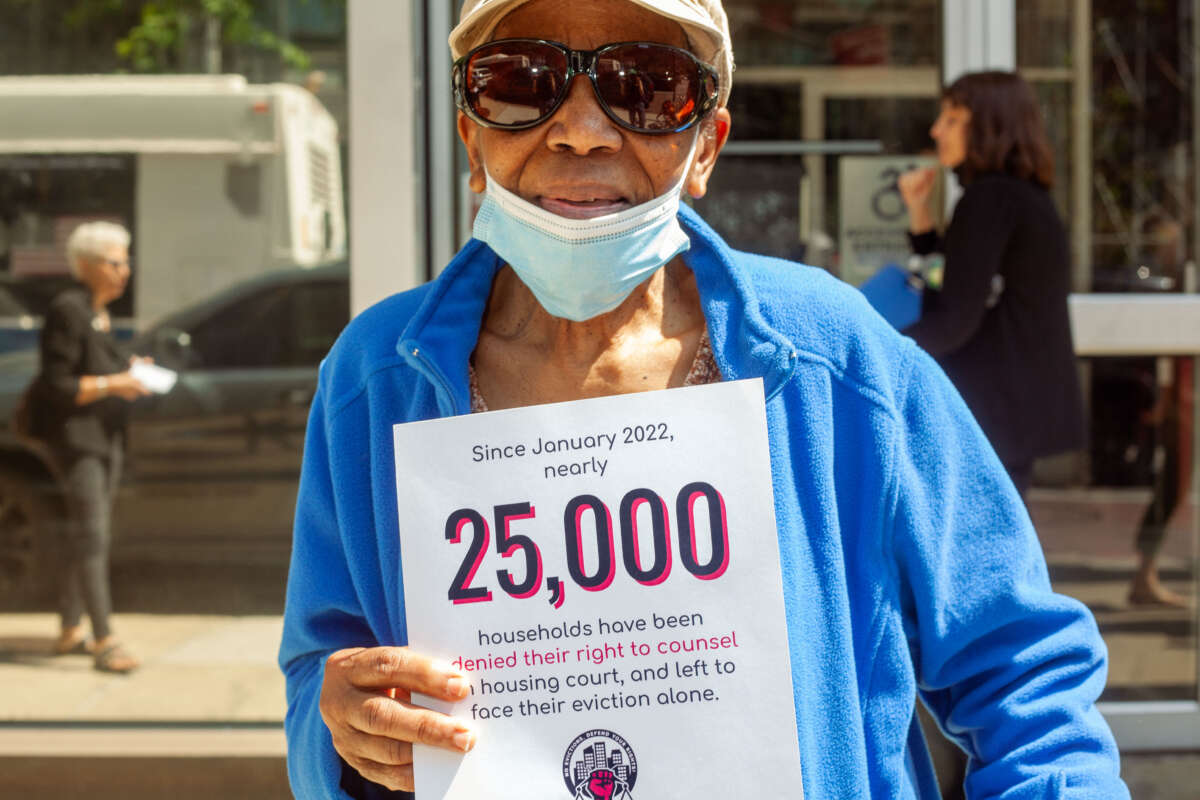

Shani Kass, an organizer with HOPE: Housing Organizers for People Empowerment, a Brooklyn, New York, tenant group led by older Caribbean-born women, is similarly encouraged by both local and national resistance. “Many of the leaders of HOPE have lived in their homes for decades. They’ve raised families in them, but now when they complain about conditions, they are laughed at or ignored by their landlords. But these tenants are fierce,” she said.

And unlike younger tenants, because they are retired, they typically have time to go to court and attend daytime protests. “They’ve seen a lot in their lives and are not going to be pushed out of the way,” Kass concludes. “These seniors know their rights and are becoming a force to be reckoned with.”