Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

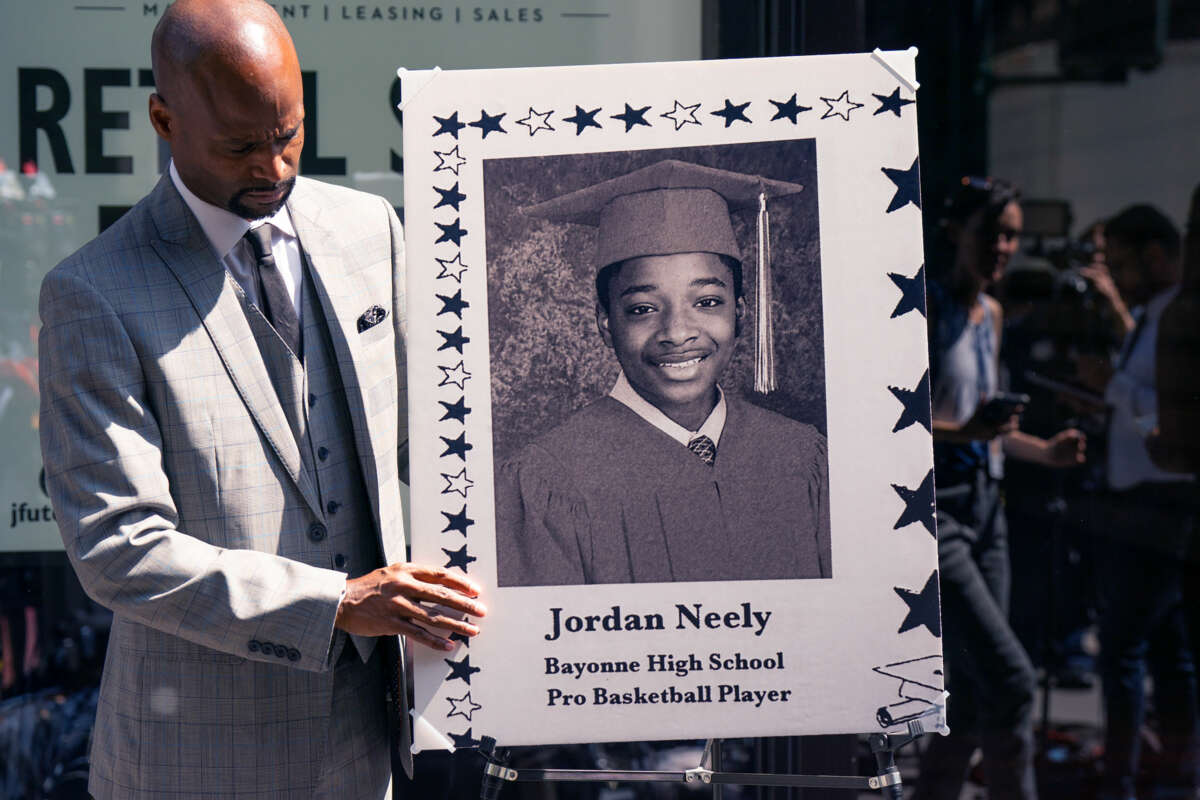

The murders of Banko Brown in San Francisco and Jordan Neely in New York City have illuminated the demonization that unhoused people, who are disproportionately Black in both cities, face from political leaders, media and the public alike.

The senseless murders of Brown — a 24-year-old Black transgender man struggling with housing insecurity who was shot to death by a Walgreens security guard on April 27 while trying to exit a store in downtown San Francisco carrying $14 of unpurchased candy — and of Neely — a 30-year-old Black unhoused subway rider who was choked to death by a 24-year-old white ex-Marine in New York City on May 1 after having shouted about his hunger, thirst and distress — have also resurfaced conversations about how dominant society treats Black men as inherently “dangerous.”

Following the murders of both Brown and Neely, many political leaders, media outlets and legal decision makers alike responded with rhetoric and decisions that underscored their apparent assumption that the murder of unhoused Black men (and particularly Black men who are trans like Banko Brown, and Black men who are disabled with mental health issues exacerbated by trauma like Jordan Neely) can be justified by the mere discomfort of others in their presence — a discomfort stoked through racist fearmongering about rising crime fostered by corporate media and politicians. Just this week, in San Francisco, the DA released the video of the security guard choking, beating and lying on top of Brown before murdering him, and still decided not to press charges while conservatives rushed to the defense of Neely’s murderer, raising almost $2 million.

These conversations about the murderous cost of white discomfort and fear as a response to poor Black unhoused people are essential to have and we noticed what is absent in many critical analyses of the aftermath of these murders is a discussion of the specific systems that failed these Black youth prior to their murders. We must name and acknowledge the role these systems played in their criminalization. Both Banko Brown and Jordan Neely became housing insecure as children, between the ages of 12-14, a time when Black youth are often imagined as older, less innocent and more dangerous.

Banko Brown was sent to juvenile hall. Jordan Neely was sent to foster care.

The foster care and juvenile justice system are deeply interconnected, with Black youth being overrepresented in both systems. The foster care or child welfare system has been described as the family policing system, because of how it is built on a history of Black family separation, and how it targets Black families disproportionately into the present day. Once in foster care, Black foster youth have longer stays, are more likely to be in group homes instead of foster families, and are less likely to be adopted.

The juvenile “justice” system has a stated purpose to “rehabilitate” youth, but it’s not working. The system spends inordinate amounts of money (some estimates say it costs $1 million a year to imprison a single youth in San Francisco’s juvenile hall), yet outcomes are often negative including lower high school completion rates and increased likelihood of being jailed as an adult. Even when youth finally get mental health support during incarceration, some report that it is rooted in changing their “criminal” minds, positioning them only as offenders and rarely as victims of interpersonal and institutional violence. This is why many activists and scholars alike have started referring to this system as the juvenile legal system, because there is no justice to be found in caging young people.

Banko Brown and Jordan Neely needed to be met with care as Black youth who became housing insecure, and instead, our society’s response was to police them. Both were arrested multiple times. The standard U.S. response to Black youth who need support is to subject them to repeated encounters with police, a profession vastly underprepared to show compassion to Black youth. For some youth — like Ma’Khia Bryant, Adam Toledo and Anthony Johnson — these police encounters are deadly. Young people who survive interpersonal and institutional violence often end up being sent to carceral systems — like the family policing and/or the juvenile legal system — that were not built for compassion but for punishment.

We can still do better for Black youth now by providing them with the resources and care they need to survive and thrive.

The ties between the murders of Jordan Neely and Banko Brown were numerous. Both of them were Black. Both were multiply marginalized: One was disabled and the other was trans. They were both unhoused and heavily policed. And their histories tell us that both Banko Brown and Jordan Neely were met with policing as unhoused Black youth when they needed compassion. Being Black and trans and Black and disabled meant they were susceptible to being heavily policed and punished rather than offered social supports.

What does it mean that these two Black youth in crisis were shuffled into two carceral systems better known for their harm against Black people than their compassion? What does it mean that these two carceral systems often implement more institutional violence to our Black youth already harmed by violence?

Instead of fixing the society that harms trans and disabled Black youth, the state disappears them into carceral systems because these children remind us of society’s failures. And when they return to society — because young people who are disappeared into broken systems are then spit out of those broken systems without material resources and with the additional trauma that these systems produce — they are often in even more danger than when they entered. This is state violence amassed against Black youth. They are being tossed into systems where we spend money to confine but rarely to care. Banko Brown and Jordan Neely came out of the juvenile legal system and the family policing system without the resources needed to survive and they continued to be unhoused and invasively policed. These carceral systems they were thrown into as Black youth did not divert them into safer pathways.

Despite the harm caused to them, Jordan Neely and Banko Brown still fought for others. Neely “would share the earnings from his Michael Jackson impersonations with other (foster) kids who couldn’t afford food or needed a haircut.” Banko Brown was a community organizer with Young Women’s Freedom Center, who fought for other youth thrown away by these same carceral systems.

These two carceral systems-impacted young people were not offering the solution proffered by leadership in New York and California: involuntary hospitalizations. Instead, both Banko Brown and Jordan Neely enacted and envisioned solutions that put material resources in the hands of young people. Yet many politicians have offered involuntary hospitalizations as a solution for unhoused people with mental health issues.

To be clear, involuntary hospitalization is imprisonment. These places are prisons. And these “mental health hospitals” also often result in Black death, such as the death of Stephen Gaines, better known as Zumbi of Zion I. Black youth are being harmed by systems purported to serve them. And if we understand that we have already shuffled these young people through several broken systems, why would we (re)create another one except to further disappear them? We cannot feed Black disabled and Black trans youth back into the broken carceral systems that have already harmed them, and we cannot (re)create new carceral systems to harm.

Unfortunately, as the U.S. returns to “tough on crime” and “keep communities safe” rhetoric, even though crime is at historic lows, we continue to put Black disabled youth and Black trans youth in danger. Whose safety are we concerned with? Some leaders in cities like New York and San Francisco have decided that the displays of poverty wrought by extreme inequalities have become bothersome. So, these cities have returned to policies we know do not produce safety but that are aimed at allowing the public not to witness poverty — policies that disappear those who are suffering. But “tough on crime” rhetoric, while effective with some voters, actually positions us to keep going back to solutions that are ineffective.

New York City Mayor Eric Adams and San Francisco Mayor London Breed know that criminalization does not produce more safety, yet both have repeatedly increased police budgets while decreasing social services. We have already invested in hyperpolicing and mass incarceration while underfunding a social safety net; these policies and practices did not prevent the murders of Jordan Neely and Banko Brown. Nor do those things keep everyone else safe. Instead the rhetoric that situates the unhoused as dangerous and needing imprisonment has now translated to the deputization of others to act with the same brutal, death dealing force as police.

Black youth, especially those who are trans or disabled, are trying to survive. Banko Brown and Jordan Neely had been trying to survive since they were young people navigating carceral systems that were not made for compassion. But these carceral systems are tying these cases so tightly together, they are forming a coast-to-coast noose.

Abolition is a portal to the destruction of carceral systems that entrap Black disabled and trans youth and the creation of systems of care. Abolition is not about reforming prisons or family policing or creating new places for mass incarceration to invade (e.g. homes and communities via surveillance technology). Abolition is rejecting a commitment to punishing and disappearing those who are harmed by violence. Abolition is about the “the presence, instead, of vital systems of support that many communities lack.” Abolition is not some utopia that can never occur. Abolition requires reimagining justice through policy and budget choices: taking the money that we spend on police and prisons, and the money we are about to spend on involuntary hospitalizations, and investing those resources in young people.

We need to invest in guaranteed housing and universal basic income, which have both shown to be effective in reducing violence. We need to create community health clinics in every neighborhood that offer mental and physical health services rooted in compassion, and make health care truly free to all. Most importantly, we need to listen to young people with experiences within and across carceral systems who are asking us “to divest from youth prisons and invest in community-based supports.”

When Black trans and Black disabled youth experience housing instability, they deserve systems that react to them with compassion. Jordan Neely and Banko Brown deserved better. But we failed them. The carceral systems we have invested in failed them. We are partly to blame for their deaths. We can still do better for Black youth now by providing them with the resources and care they need to survive and thrive.

Trump is busy getting ready for Day One of his presidency – but so is Truthout.

Trump has made it no secret that he is planning a demolition-style attack on both specific communities and democracy as a whole, beginning on his first day in office. With over 25 executive orders and directives queued up for January 20, he’s promised to “launch the largest deportation program in American history,” roll back anti-discrimination protections for transgender students, and implement a “drill, drill, drill” approach to ramp up oil and gas extraction.

Organizations like Truthout are also being threatened by legislation like HR 9495, the “nonprofit killer bill” that would allow the Treasury Secretary to declare any nonprofit a “terrorist-supporting organization” and strip its tax-exempt status without due process. Progressive media like Truthout that has courageously focused on reporting on Israel’s genocide in Gaza are in the bill’s crosshairs.

As journalists, we have a responsibility to look at hard realities and communicate them to you. We hope that you, like us, can use this information to prepare for what’s to come.

And if you feel uncertain about what to do in the face of a second Trump administration, we invite you to be an indispensable part of Truthout’s preparations.

In addition to covering the widespread onslaught of draconian policy, we’re shoring up our resources for what might come next for progressive media: bad-faith lawsuits from far-right ghouls, legislation that seeks to strip us of our ability to receive tax-deductible donations, and further throttling of our reach on social media platforms owned by Trump’s sycophants.

We’re preparing right now for Trump’s Day One: building a brave coalition of movement media; reaching out to the activists, academics, and thinkers we trust to shine a light on the inner workings of authoritarianism; and planning to use journalism as a tool to equip movements to protect the people, lands, and principles most vulnerable to Trump’s destruction.

We urgently need your help to prepare. As you know, our December fundraiser is our most important of the year and will determine the scale of work we’ll be able to do in 2025. We’ve set two goals: to raise $150,000 in one-time donations and to add 1,500 new monthly donors.

Today, we’re asking all of our readers to start a monthly donation or make a one-time donation – as a commitment to stand with us on day one of Trump’s presidency, and every day after that, as we produce journalism that combats authoritarianism, censorship, injustice, and misinformation. You’re an essential part of our future – please join the movement by making a tax-deductible donation today.

If you have the means to make a substantial gift, please dig deep during this critical time!

With gratitude and resolve,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy