Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

What is a Catholic Worker?

The Catholic Worker, in an act of protest against The Church, was originally a newspaper speaking on issues of human rights and civil liberties. Dorothy Day then began housing and feeding the homeless from two houses in Manhattan called Maryhouse and St. Joseph’s. Maryhouse serves a full lunch to women four days a week, provides showers and opens its clothing room all within two hours, four days a week. Saint Joseph’s serves soup in the morning, closes for lunch and opens its doors for another two hours in the afternoon to offer clothing, five days a week. In addition, each house houses about 20 residents and volunteers. The CW has never been recognized by The Church, does not pay war taxes, is not subsidized by government funds, is fully funded by private donations, and still publishes its newspaper today at one cent per copy. 100,000 copies are circulated each month. Today, there are over 300 Catholic Worker homes and farms globally.

In February of 2014, still having been new to the city, I moved from Brooklyn into a Catholic Worker house located in the east village of Manhattan. Once a neighborhood where the “Bowery bums” inhabited, it is now home to Philip Glass and other 20- to mid 30-year olds here to “make it.” I began helping serve lunch in the mornings and quickly started cooking meals for about fifty people on my own. I also took shifts in the evening until 10 p.m. Like many who chose to live at Catholic Worker, I wanted to find my place in the world. Like many Catholic Workers, I am too gentle to live among wolves. This would be where I could live with idealists who despise war, continue my work on closing Guantanamo Bay Prison, take care of others, and not become apathetic. I know this because I’ve spent the past five years with Catholic Workers, coming from Witness Against Torture. And like many Catholic Workers, I found myself asking, “What am I doing here?

In a journal entry I wrote:

I’ve been here for three weeks now and I think I’m going crazy already. I knew it wouldn’t be easy or comfortable. All my life, I have struggled with trying to find some peace–to live freely. Today, this place is driving me crazy. I have been doing a lot of reflecting these past two days and trying to find my rhythm in the house. To help me, I’ve been reading some of Dorothy Day’s philosophies and reading archives of the Catholic Worker paper. I found something from Michael Scahill.

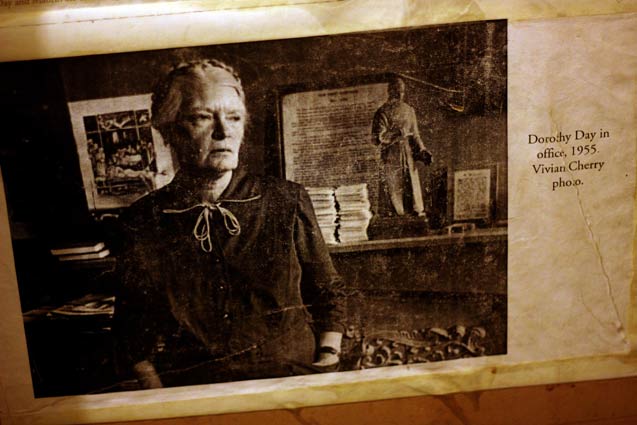

Archives room, Maryhouse, Februrary 2014. (Photo: Palina Prasasouk)

Archives room, Maryhouse, Februrary 2014. (Photo: Palina Prasasouk)

I continued on to write a timeline of the abuses I suffered in my childhood, to the bouts of depression in my 20s, to being a single mom, and my career choices leading up to my current life in New York City. I quickly learned that I needed to lower my standards as a Catholic Worker. I thought if I could read about Dorothy Day’s life and what the CW was like when she was alive, I would understand my purpose at Maryhouse better. In the archives, I found a remembrance piece from a November 2005 birthday issue, “The Freedom to Become” by Mike Scahill. Jackpot—this is what I want too, Mike! It was a follow-up to an article he wrote in 1970 entitled “Up From Nonviolence.” The piece eventually lead to his departure from the CW. The title of Scahill’s article, “The Freedom to Become” comes from Dorothy Day, “Being and becoming are two different things.” All I knew is that I wanted the “freedom to become,” but is that not the same as “becoming?” What the hell does that mean?

What am I Doing Here?

I began making rounds with volunteers asking them where they came from, how they got here, and what they do when they’re feeling overwhelmed. I was once homeless myself and told Theresa Kelly, a hard-assed Bronxite, “This is worse than being homeless.” Slightly offended or maybe confused, she asked me, “Why?”

Because we have to work and live in the same place.

Theresa went on to tell me that the “evil one” doesn’t want us to do God’s work. “I hate him so much that I can’t even say his name, but I can smell him, oh I can smell him a’ight.” I also spoke with an Irish seminarian named James while out drinking with other seminarians. He told me to ask God if he’s real. James had a magical accent and gentle hands and he seemed to understand me. One night, I kneeled in front of the Eucharist and asked God inside my head, “I met a man named James, at a bar called Heroes and he told me to ask you if you’re real. Are you real? Make a sign.” Nothing happened, and clearly I was losing my mind.

Somehow, Mike’s article brought me a sense of comfort after hard days–days when I was told I “wasn’t around enough to voice my opinion” at meetings, that maybe “this wasn’t the place” for me, that I had to have a “special calling” in order to raise my child there because I’m “on a community quest, not spiritual quest,” that I “deceived” my way in and that “we’re not all equal.” This was not, to my knowledge, what Dorothy Day had envisioned. It was to my understanding that I was serving the hungry–the women, from whatever circumstances, coming in to eat and shower, did not deserve to die on the streets. Knowing that Mike also didn’t feel comfortable at the Worker some 40 years ago, made me not feel alone in a house of twenty people over the age of 58 where I am the only non-Catholic. In his “Up From Nonviolence” piece he writes:

I have worked at many jobs in the states ranging from office work to construction and I can recall that every time I reflected on the meaning and value of my work and who it benefited, I became terribly depressed and even felt like quitting.

Me and this guy had something in common and I needed to talk to him. It seemed that Maryhouse has had a history of young people, particularly women leaving it. I needed to speak to someone who will be forthcoming with me.

An Odd Series of Events

Though, as depressed as I was from having to leave my daughter with grandma in Iowa, I wanted to stay at Maryhouse and try to make something work. There were things I heard and saw that I did not agree with, and I questioned my own pacifism when defending myself. During a visit to Des Moines, Iowa, I told Jeremy Scahill that I found a couple of articles from his dad. I wanted to send him a letter, but never took down his e-mail address. Someone interrupted us before I could ask him what he meant when he said (in a Vice interview) he used to think he was nonviolent. I cornered Jeremy again and told him I had some more questions. He said, “Yeah, but I’ll be watching the game.” Calm down, Palina! You’re stalking him like he did with Amy Goodman. After missing my flight back to NYC due to a taxi error, I was bumped to first class where I found myself sitting next to Jeremy. “What an odd series of events,” I said sitting down. He looked at my ticket and noticed I was sitting in the wrong seat. Oh, I guess we’re not going to talk about nonviolence for two hours anymore.

A couple of weeks later, Mike Scahill, now a pediatric nurse in Milwaukee, visited Maryhouse where I could tell him myself about what I had found. Behind a white mustache, a little smile emerged as he proudly said, “So, you’re from Iowa. There’s something special about people from the Midwest.” Following his visit, in a phone conversation with Mike, I asked him if words can be violent:

There could be a time where people could engage in the right to self-defense. I believe that aggression and verbal abuse is violent. Microaggressions often times escalates and has ties with domestic abuse. Emotional abuse is as damaging as physical abuse.

I then expressed to Mike that I felt like I was being attacked at the house and asked him what he thought Dorothy Day meant when she said, “The freedom to become and becoming are not the same.” He said, “We always want to be in the process of changing and not be afraid not to change.” After asking Mike more questions such as, “Were there lesbians and homosexuals who were kicked out from the Catholic Worker?” It was clear that I didn’t have a singular direction, and he asked me what this interview was for. I said, “I’m not sure. I would like to write a piece on what nonviolence is. Maybe it will be for my auto-biographical self-help book.” (Maybe I just wanted to talk to Jeremy Scahill’s dad.) I wanted to know the story behind “Up from Nonviolence.” Some had told me that Dorothy Day “had a fit.” According to Mike, it was discussed in a Friday night meeting and it was her decision to place it on the front page. Dorothy had accompanied Mike’s piece with her “On Pilgrimage” piece:

So it is good for us to be confronted with a David (Miller) and a Michael and recognize that we do not deserve, have not earned the title pacifist or Christian….I feel that these young men have grown in honesty and seriousness. They have begun to see what study lies ahead. We need to learn from others, and from the struggles going on in India, Africa, China, Russia and Cuba.

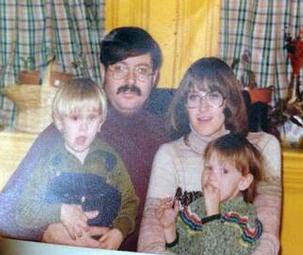

The Scahill family, 1977. (Photo: Jeremy Schill / Twitter)Subscriptions of the paper were canceled and hate mail was sent. House mates were not friendly with him. After departing from the Catholic Worker on his own accord, he went on to practice medicine and met his wife Lisa, a fellow nurse. They had three children—all attended a Catholic school where they were the minorities in a predominantly African-American neighborhood. Lisa and Mike raised all the children in a lower middle-class home intentionally. The eldest, Jeremy went on to spend several years working in homeless shelters on the east coast. Like his father, he lived in voluntary poverty on the fifth floor of St. Joe’s.

The Scahill family, 1977. (Photo: Jeremy Schill / Twitter)Subscriptions of the paper were canceled and hate mail was sent. House mates were not friendly with him. After departing from the Catholic Worker on his own accord, he went on to practice medicine and met his wife Lisa, a fellow nurse. They had three children—all attended a Catholic school where they were the minorities in a predominantly African-American neighborhood. Lisa and Mike raised all the children in a lower middle-class home intentionally. The eldest, Jeremy went on to spend several years working in homeless shelters on the east coast. Like his father, he lived in voluntary poverty on the fifth floor of St. Joe’s.

The Catholic Worker Movement Will Continue

After sitting on this interview for six months now, I still don’t know what nonviolence is. (Wait, that wasn’t six months ago. It was two months. Time goes by slowly.) Mike suggested that I write a piece on child sex abuse for the CW, something that has never been done before. He offered to read anything I write, so for that I am grateful. After all, he is father to one of the world’s most influential journalists.

Carmen Trotta told me some people would be angry if I didn’t submit my piece about nonviolence to the CW. By some people, he meant him and I’ll take a pass in order to dodge more backlash. I have enough people who hate me and would rather avoid conflict with people who are on the same side. I’ve got a firmer grip on what would make Maryhouse better, but my daughter is depressed here. A wise and also disliked man around the CW once said, “Are you here for them or the women?” – Brian Hynes

I can also say that I have learned what Dorothy Day meant. I think she was trying to say that Maryhouse will always be a school, which is ironic because it was formerly a music school. I take away with me, my own quote heard at the CW:

We do nice things, but we aren’t nice people. – Jim Reagan, volunteer resident

This has been a valuable exercise in the acceptance of absurdity. Like any establishment that involves humans, it will always be flawed because people are imperfect. At the end of this month, we will be moving to the Bronx where I will attempt to make a living, and homeschool my daughter in order to keep up with my travel schedule and her boredom from public schooling. We hope to never have to say again, “Who keeps taking the damn soap from the bathroom?!”

I wish I could say I will miss living here, but it’s summer and the bed bugs are in heat. I have made life-long relationships and have pushed my boundaries. I would probably do it again, but just not at Maryhouse. But I wouldn’t move back in with Mom either. I truly love everyone here and in 30 years I will probably say the same thing as Mike Scahill:

It was as if I had left a meeting to step outside to have a cigarette for 30 years, and then went back inside. The same meeting was going on. The issues, the problems, even some of the same.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to raise $50,000 in the next 9 days. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.