Part of the Series

Beyond the Sound Bites: Election 2016

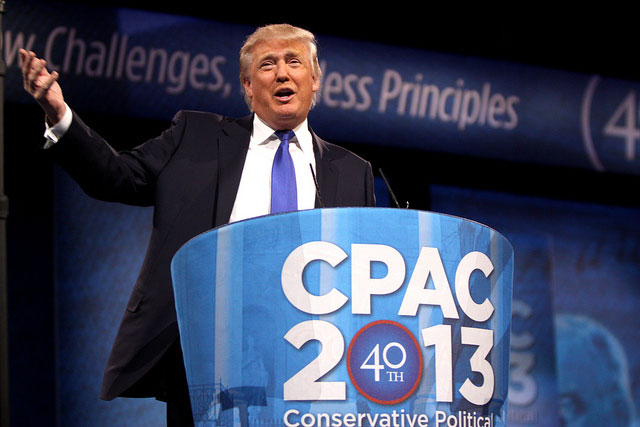

The rise of Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump is a clear symptom of the catastrophic normalization of authoritarian capitalism around the world. Many recent debates about his popularity, however, have missed this point: They are being framed in post-ideological terms that obscure the relation between Trump’s rise and the deepening contradictions of the global capitalist system.

In its recent worldwide restructuring process, global capitalism has forcefully embraced authoritarian values that promise to sustain capitalist growth. This results in disastrous consequences to personal freedoms and economic security and justice for large unemployable segments of the population. Trump’s brand of populist, protectionist and isolationist economic policies resonate with the current sharpening of the contradictions of the hegemonic global capitalist system, revealing how US neoliberal capitalism is in imminent danger of a transformation into authoritarian capitalism.

Trump’s objection to outsourcing, rejection of free trade treaties and his call for more government economic intervention are all symptoms of the fact that neoliberal economic policies and the democratic values associated with them can no longer drive capitalist growth. As a result, the crisis of global capitalism today is driving nations worldwide toward new forms of politico-economic organization — namely authoritarian capitalism.

Many critics have lashed out against Trump’s fascist rhetoric, coded Nazi gestures and incitement to violence, but in truth these are merely the tip of the iceberg.

The Authoritarianism Debate

In a recent national study that received wide attention, political researcher Matthew MacWilliams concluded that the strongest measure of voters’ support for Trump in the South Carolina Republican primary was their authoritarian attitudes. He identified various common behaviors to which these voters seem to be disposed: They enforce conformity and stability, have zero tolerance for deviance, maintain social norms, scapegoat the Other, obey aggressive and violent leaders and fear the threat of terrorism. MacWilliams thus warns that such attitudes usher in “America’s Authoritarian Spring” and serve as a clear indication that “rising authoritarian attitudes [are] playing a newly significant role in American politics.”

In the “black-and-white” or the “us-versus-them” worldview of these voters, all other usual indicators — including age, gender, education, income, race, party identification, religious denomination (evangelicalism) or even ideology — failed to predict with statistical significance these voters’ support for Trump.

Americans and Ideological Heterotopia

Other social scientists dispute this authoritarian moniker and try to fill in the gap of MacWilliams’ study with regard to ideology and other issues but end up normalizing authoritarian capitalism in Trump’s campaign. In a series of articles for The Washington Post, John Sides and Michael Tesler propose different theories to explain the rise of the heterodox candidate Trump in US populist politics. The two that are most relevant here have to do with the allegedly nonideological dispositions of most US voters and the economic struggles that US voters experience.

Sides and Tesler first claim that most US voters, including many Republicans and the less-educated voters that Trump loves, are not ideologues. That Americans are allegedly “innocent of ideology” is one of the truisms of US political science. According to this myth, voters are most likely to have political views that are incongruent with the party line, rarely use ideological terms and concepts to describe their political dispositions and fail to offer coherent definitions of dominant political theories, such as liberalism and conservatism. This, nonetheless, hardly proves they are “innocent of ideology” or ideologically inconsistent.

Indeed, the claim that Americans are “innocent of ideology” is itself purely ideological in that it is meant to obscure the capitalist ideology that structures the totality of the US system. Ironically, the truth of Sides and Tesler’s pure ideological ruse becomes apparent in their last installment on income and economic struggles. Drawing on the work of the political scientist Phillip Converse, Sides and Tesler highlight the importance the economy plays in voting incumbent parties in or out in elections. They show that Trump has found strong support among lower-than-average-income voters, as well as voters whose personal finances have declined and those who were not satisfied with their situation a year earlier.

Therefore, they say, Trump’s message of economic mobility resonates with these voters. “Trump is constantly telling voters how his own personal greatness will lead to prosperity,” adding that, “Not only will he make America great again, but he will make America rich again.” The fact that Trump has an abysmal business record does not seem to concern his supporters. Nor do they seem to care that upward mobility has not changed in the last decades, as a 2014 study of millions of anonymous tax records shows.

Sides and Tesler, however, fail to link these claims about ideology and the economy together, and end up obfuscating the shift into authoritarian capitalism. Their analysis falls short of exploring the full implications of the behavior of US voters, who will deviate from the mainstream of their party and will question and complain about their declining fortunes — except when it has to do with global capitalism, which serves as the inexorable frame or ideology that defines their lives and gives it meaning.

Populism and Capitalist Rationality

This obfuscation is also obvious in Wendy Rahn and Eric Oliver’s critique of MacWilliams’ claims about authoritarianism. Rahn and Oliver argue that Trump’s supporters are more populist than authoritarian, claiming that authoritarians identify with political and economic elites, whereas populists oppose elites, mistrust intellectuals and experts, have a strong (white) nationalist identity and call for the protection of the “people.”

The researchers, however, do not explain what these populists seek protection from, nor do they really make clear the underlying contradiction in the populist definition of the term “elite.” First, they imply that populists see themselves as victims of multicultural politics — that all these people of color and “outsiders” are staking claims to what they perceive to be rightfully theirs. Power, privilege and entitlement are prerogatives conferred upon people of European descent as a result of their automatic membership in the “white club,” and no person of color should have access to them.

Second, these researchers claim that populists “often fear not just political elites and billionaires, but anyone who claims expertise.” However, they do not seem to find this contradiction between the populist support for Trump and the populist definition of power and economic elites that includes billionaires worthy of any reflection or critique. That populists do not seem to count Trump as one of the elite billionaires and that they downplay his longtime involvement in politics is a function of the ways in which authoritarian capitalism is erased and made invisible at the moment it is inscribed.

Trump’s program is far from, in Matthew Cooper’s words, “busting ideological barriers.” Indeed, Trump appeals to these populist voters not because they are deeply dissatisfied with capitalism, but because they are more likely unhappy with the operations of democracy and its multicultural ideology today. If they were in fact dissatisfied with capitalism, the truth of the fundamental antagonism would not be obfuscated by Trump’s xenophobic, fearmongering rhetoric. They would have seen through it and would have probably reinvented the US political system.

Trump’s Anti-Semitic Zionism

The same contradiction that lies at the heart of Trump’s populism also defines his platform on US foreign policy, in general, and the United States’ unconditional support for Israel, in particular. Trump’s position on Israel can be best characterized as anti-Semitic Zionism: While his rally pledges have been compared to the Nazi quenelle, in a clear attempt to pander to white supremacists, and his speeches have recycled pernicious anti-Semitic stereotypes, his neutral posturing on Israel belies his declarations of unequivocal commitment to Israel.

However, neutrality does not necessarily mean impartiality. Especially in the context of an asymmetrical struggle between a regional military and economic superpower like Israel and a non-state entity like the Palestinian Authority, neutrality could simply mean granting Israel free rein to expand its settler-colonial project as it deems fit in Palestine.

Early this month, moreover, Israel Hayom (Israel Today) seemed to endorse Trump, however indirectly, in the name of Islamophobia as the Republican Party’s presidential nominee. This Israeli daily newspaper was established by the American billionaire and Republican mega-donor Sheldon Adelson for the purpose of serving as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s propaganda platform. This leaves little doubt as to the prospect of an alliance between Trump and billionaires who do business with authoritarian capitalist regimes and who unconditionally support totalitarian democracies. This does not bode well for the future of a free and independent Palestinian state.

In 2012, Trump launched a vitriolic Twitter campaign against President Obama’s second election, in which he called the Electoral College system a “disgusting injustice.” Trump added, “This election is a total sham and a travesty. We are not a democracy! We can’t let this happen. We should march on Washington and stop this travesty. We should have a revolution in this country.” Trump seems to be getting his “revolution” and it is in danger of leading us all into authoritarian capitalism.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $50,000 in the next 9 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.